How Clergy Set the Standard for Abortion Care

Fifty years ago, a network of religious leaders helped thousands of women find safe, comfortable ways of having the procedure.

Supporters of abortion regulations like those at issue in the Supreme Court case Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt claim they are trying to raise the standard of health care for women. But overly medicalized abortion procedures are not optimal for patients. An unlikely group taught that lesson over 40 years ago: the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion. When New York legalized abortion in 1970, these religious leaders opened a clinic, moving the procedure out of hospitals and modeling abortions that were affordable, accessible, and comfortable for women.

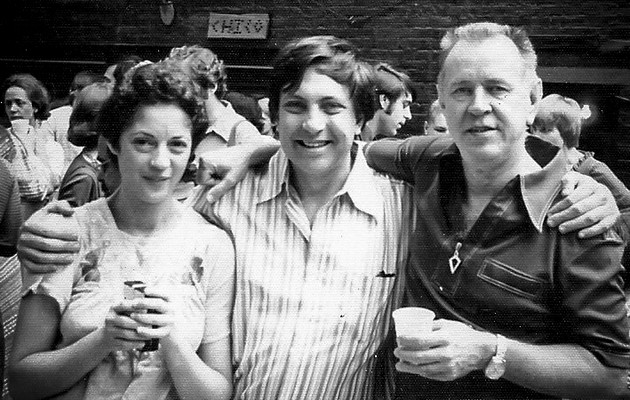

In 1967, Howard Moody, the senior minister of New York City’s Judson Memorial Church, told The New York Times that a group of 21 Protestant and Jewish religious leaders would offer women with unwanted pregnancies counseling and referrals for safe abortions. By 1973, roughly 1,400 clergy members across the country had helped what’s estimated to be hundreds of thousands of women access safe abortions.

Moody documented the work of the New York Clergy Consultation Service in a 1973 book, Abortion Counseling and Social Change, written with his Judson Memorial colleague, Arlene Carmen. It’s a surprising read today. Written before religious opposition to abortion was widespread, Moody and Carmen spend few words on the morality of abortion; they treat the pastoral obligation to help women access safe, affordable abortions almost as a given. Instead, they focus on the practical realities for women in need of dignified abortion care, offering insights into how the service should be delivered to best serve patients that contrast sharply with today’s trend toward laws mandating overly medicalized abortion procedures.

The thousands of women dying from unsafe abortions in the U.S. in the 1960s were disproportionately poor women of color. Moody and Carmen expressed special disdain for “therapeutic abortions,” which allowed women with money and connections to receive legal abortions by getting a friendly physician or psychologist to deem a pregnancy life threatening—the only circumstance in which abortion was legal under New York law. “‘Therapeutic,’” they wrote, “was only a term to describe the difference between rich and poor, white and black, the privileged and the underprivileged, married and single.”

Women who couldn’t get therapeutic abortions resorted to self-abortion or sought out illegal providers. Another minister in Florida once called upon Moody to help a parishioner get an abortion, he writes in his book. He travelled with the woman to see a New Jersey doctor operating out of his house, only to be turned away because they didn’t have the code word. After a number of other leads didn’t pan out, a church member finally found the woman a provider doing abortions in an apartment in Manhattan. Moody “never forgot this first glimpse of that dark, ugly, labyrinthine underground into which women were sent alone and afraid.”

Moody compared the initial reluctance of some of his colleagues to get involved to the early days of their work in the civil-rights movement, when some had believed their communities didn’t have a race problem because they didn’t have any black people. He insisted that if the clergy made themselves available to women, they would discover how great the need was and understand their obligation to address it.

The first order of business was “self-education.” Moody and founding members of the CCS met with women who had had illegal abortions to learn what the experience was like and what would have made it better. On another occasion, a physician demonstrated the abortion procedure using a pelvic model; Moody and Carmen called it “the day the clergy went to medical school.”

Once they launched the referral service, the members of the CCS came to see themselves as consumer advocates in addition to pastoral counselors. The organization created a kind of pre-Internet Yelp for illicit abortion providers. When a physician willing to provide abortions was recommended to the CCS, Carmen would pose as a woman seeking an abortion to investigate his office and bedside manner and inquire about his technique. The counselors encouraged all women to report back about their experiences, and after a woman was referred to a new doctor, her counselor would follow up for her review.

CCS members realized early on that price was as great a barrier to safe abortion as illegality. They shared information about pricing with women and negotiated with doctors to drop their rates. As what was thought to be the largest referral service in the country, which referred an estimated half million women for abortions in its six years of existence, the CCS had significant market power that it leveraged to reduce the going rate for an abortion. When a doctor charged more than the agreed upon price or added fees, the CCS would stop referring to him, cutting off a lucrative source of patients until he agreed to their terms.

Despite the efforts of CCS members to reduce the cost of abortion, they knew they were almost exclusively helping white women who could afford the procedure and costs of traveling to obtain it. When abortion became legal in New York in 1970, the New York CCS felt obligated to ensure demand for the procedure could be met and “early, safe, inexpensive” abortion would be available to all. Three years of referring women for illegal abortions had left Moody and his colleagues with “firm convictions about the innovations that would be necessary to provide safe, low-cost, and humane abortions.” The most central of these convictions was that abortions had to be moved out of hospitals and into freestanding clinics, a less expensive and intimidating setting for a simple procedure patients needed to get in a timely manner.

So the clergy opened an abortion clinic. They partnered with a doctor, Hale Harvey, and a clinic administrator, Barbara Pyle, to create Women’s Services, a clinic built to model “low cost, quality care, humane treatment, and a willingness to serve the poor.”

The facility was decorated in bright colors to create a warm and intimate atmosphere. Harvey believed even a healthy patient would feel sick in a cold, sterile environment: “Since abortion was not a sickness, the atmosphere associated with hospitals needed to be avoided,” as Moody and Carmen summarized his logic. Harvey had been particularly popular among the CCS doctors in the days when the procedure was illegal because of his efforts to make the experience less intimidating: putting colorful potholders on stirrups to make them more comfortable and attractive and giving patients cookies and sodas after their procedures.

With the exception of a few doctors who had provided outpatient abortions, the medical community saw the clergy as inexperienced laymen, according to Moody, and did not support their plans to move abortion services out of hospitals. It wasn’t the first or the last time Moody and his colleagues at Judson Memorial would provide medical services in ways that made the medical community look askance: Judson Memorial established the first Greenwich Village drug-treatment clinic in 1959; a Center for Medical Consumers aimed at giving patients more control over their medical treatment in 1976; and the People With Aids Health Group to give AIDS patients access to experimental treatments in 1987.

Having referred thousands of women for abortions in doctors’ offices with few complications and no fatalities, the CCS members believed abortions could be performed safely in an office setting, where medical providers could meet the demand for low-cost abortions that hospitals couldn’t. With branches of the CCS from across the country referring patients, the clinic served more abortion patients than all of New York City’s hospitals combined, according to Moody’s and Carmen’s book. The clinic charged $200 for the procedure when it opened, which was well below the market rate, and was able to further reduce the price to $125 within a year. Patients who lacked the ability to pay—one in every four—paid only $25. Other abortion providers had to keep their prices low and patient satisfaction high to compete.

At Women’s Services, patients were counseled in detail about what the procedure would entail by other women, many who had abortions themselves. These counselors, who were not necessarily registered nurses, would also assist doctors during the procedure, which was frowned on by the medical community. But with non-physicians on staff to offer advice and help with the procedures, Women’s Services was able to maximize the number of patients its physicians could care for.

Shortly after abortion became legal in New York, legislation was proposed that would have required a woman to receive counseling from a psychologist or member of the clergy before having an abortion. The CCS members opposed this because they believed women generally arrived with their minds made up—their counseling would be of little benefit now that abortion was legal, and mandating it would only burden women with extra cost and delay.

The legislators behind today’s ever more stringent abortion regulations seem to have the opposite intention. The case the Supreme Court will soon decide, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, is a challenge to the Texas law that requires all abortions to be performed in ambulatory surgical centers, or ASCs, and allows only physicians who hold admitting privileges at a hospital to perform them.

These medically unnecessary restrictions, which would shutter 75 percent of the state’s clinics, are counter to the lesson of the CCS that performing abortions in expensive, inaccessible facilities is bad for women, and poor women in particular. When getting a legal abortion is an ordeal, some women will resort to unsafe options.

The regulations would also prevent women who do manage to get to an ASC from having the procedure in the kind of atmosphere the members of the CCS believed is integral to dignified abortion care. Like the clergy’s clinic, Whole Woman’s Health, the lead plaintiff in the Supreme Court case, is known for being particularly attentive to patient comfort. The clinic is nicely lit and decorated with inspirational quotes. Patients have herbal tea under purple blankets in a recovery room filled with recliners where their friends or family can join them comfortably. The typical gynecologist’s office is bad enough, but an ASC is a much more sterile and intimidating facility. Instead of cozying up with tea and blankets, women lie on stretchers in hospital gowns as if they’d had a major surgery. This is not the sort of thing that makes ending a pregnancy safer or more pleasant, but the Texas legislature has not seemed to share the CCS counselors’ interest in the patient experience.

Judson Memorial Church—joined by the CCS’s successor organization, the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, and a slew of other religious groups—filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court opposing Texas’s abortion regulations. They argue the measures will injure the health and dignity of women by driving up costs and decreasing access to safe abortion. Unlike the Texas legislators purporting to protect women seeking abortions, they know whereof they speak.