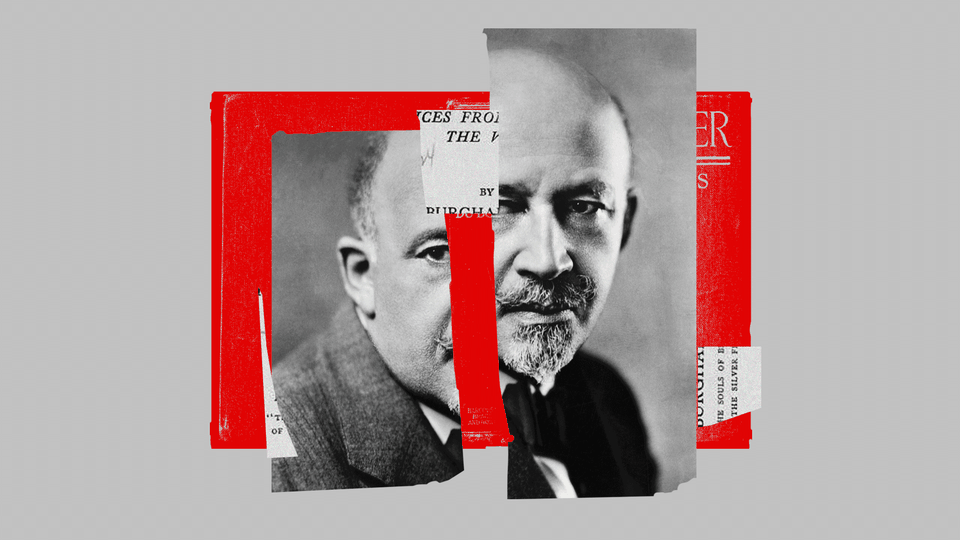

Du Bois Gave Voice to Pain and Promise

A century after the publication of Darkwater, its message has never been more relevant.

W. E. B. Du Bois was torn between hope and rage. Following the First World War, challenges to colonialism in Africa and Asia, revolutionary labor movements, demands for women’s rights and universal suffrage, and the growth of what would become the modern Black freedom struggle portended a new, radical future. However, the harsh realities of imperial conquest, capitalist exploitation, the subordination of women, and horrific racial violence remained firmly intact. Black people fought back. But, Du Bois wondered, could democracy ever become a reality for Black folks?

In 2020, across the nation and the world, people have turned out in unprecedented numbers to answer this question. We are again grappling with the failures of democracy, the specter of Black death, and the tension between faith and despair. We are again fighting to affirm the sanctity and beauty of Black life. And Du Bois’s 1920 book, Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil, offers us a clarion call to action, to imagine a better tomorrow and continue, even in the face of death, to live, to fight, and to love.

Du Bois finished the first draft of Darkwater on February 23, 1918, his 50th birthday, believing that it might very well be his final work. The previous year, he had undergone surgery to remove a damaged kidney. In the book’s autobiographical opening chapter, “Of the Shadow Years,” Du Bois wrote that he had “looked death in the face and found its lineaments not unkind.” He survived, although he felt assured that soon he would “enjoy death as I have enjoyed life.”

America’s entry into World War I had tested his resolve. Du Bois, echoing current debates about the efficacy of Black patriotism, supported the war effort and encouraged Black people to “forget our special grievances,” as he wrote in the July 1918 Crisis editorial “Close Ranks,” and stand “shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.” Du Bois was widely excoriated, with his harshest critics calling him a traitor to the race. In December 1918, Du Bois traveled to France, where along with organizing a pan-African congress, he saw firsthand the devastation of the war and heard directly from Black soldiers and officers how American racism had wounded them in body and soul. “With the armistice came disillusion,” he later recalled.

Du Bois’s disillusionment deepened by the end of the summer of 1919. Racial violence had exploded across the country, from Washington, D.C., to Chicago to Elaine, Arkansas. The lynching of Black people had skyrocketed. On August 30, 1919, in Bogalusa, Louisiana, Lucious McCarty, a Black veteran, was shot, dragged through town, and burned to the howling delight of some 1,500 spectators. Two weeks later, Du Bois submitted the final manuscript of Darkwater to Harcourt, Brace, and Howe.

The trauma of the war and the horror of the “Red Summer” explain the harsh racial world Du Bois depicts in Darkwater. Race, as an ideology and social reality, had become an immutable fact, with the modern investment in whiteness being one of its most dreadful costs. “But what on earth is whiteness that one should so desire it?” Du Bois asked rhetorically in the prescient chapter “The Souls of White Folk.” After pausing to reflect on the countless everyday acts of privilege—some silent, some ugly, all enraging—white people wielded like a weapon, he sardonically concluded that “whiteness is the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!”

In Darkwater, Du Bois reprised the image of a veil from his 1903 work, The Souls of Black Folk, to characterize the color line as inhibiting yet ultimately permeable. But this time it was much more violent and unforgiving. “There is Hate behind it, and Cruelty and Tears,” he painfully revealed. “As one peers through its intricate, unfathomable pattern of ancient, old, old design, one sees blood and guilt and misunderstanding. And yet it hangs there, this Veil, between Then and Now, between Pale and Colored and Black and White—between You and Me.” The veil, no longer solely a metaphor, was “true and terrible.”

East St. Louis, Illinois, offered a prime example. Du Bois detailed how the wartime influx of Black migrants into the city unsettled the color line, heightened labor tensions, and caused “red anger” to flame in the hearts of white workers. On July 2, 1917, it exploded. White mobs “killed and beat and murdered; they dashed out the brains of children and stripped off the clothes of women; they drove victims into the flames and hanged the helpless to the lighting poles,” he wrote. Du Bois argued that racial terror is thoroughly ingrained in the soil and psyche of America.

Darkwater also speaks to the deep roots of our current struggle with the precarity of Black life and the traumas of premature Black death. “We know in America how to discourage, choke, and murder ability when it so far forgets itself as to choose a dark skin,” Du Bois lamented. He posed questions that still haunt Black parents: “Is it worth while? Ought children be born to us? Have we any right to make human souls face what we face today.” Having lost his first son, Burghardt, in 1899 at only 18 months, Du Bois pondered these questions from a place of personal sorrow, while also writing that Black mothers felt, and continue to feel, this pain even more acutely.

At every turn in Darkwater, shadows seem to overtake the light. And yet, through the pain, Du Bois offers hope.

Darkwater was the canvas for Du Bois’s bold postwar political vision and challenge to global white supremacy. This included ending European imperialism, pursuing economic justice and the redistribution of wealth, expanding the franchise and protecting the right to vote, recognizing the struggles and contributions of Black women, and investing in education. Darkwater represents a foundational moment in the long battle for Black freedom and democracy that endures with the movement for Black lives today.

Du Bois also knew that any vision of the future for Black people had to be coupled with an appreciation for the beauty of life. In Darkwater, he wrote of his travels in the United States and abroad: the iridescent colors of the ocean in Maine; the vast living awe of the Grand Canyon; the heroic quaintness of France. “Grant all its ugliness and sin,” Du Bois wrote, “the petty, horrible snarl of its putrid threads,” but he could not forget that “the beauty of this world is not to be denied.”

And above all else, there was the beauty and gift of Blackness. Tears welled in Du Bois’s eyes as he listened to the “wild and sweet and wooing” sounds of the jazz musician Tim Brymm and his military band playing in the small French hamlet of Maron. He delighted in memories of a walk down the streets of Harlem, surrounded everywhere by “black eyes, black and brown, and frizzled hair curled and sleek, and skins that riot with luscious color and deep, burning blood.” All this and more affirmed Blackness as a life-sustaining force that even the harshest forms of white supremacy could not deny.

“Which is life and what is death and how shall we face so tantalizing a contradiction?” Just as Du Bois asked this question in 1920, we ask it again a century later. Du Bois lived until 1963, leaving behind an enormous corpus of writings for us to learn from. Darkwater, however, rings especially prophetic. Du Bois gave voice to the pain and promise, the hopelessness and faith, the rage and beauty that continue to define so much of the Black experience in America.