The Rich Get Richer—and More Educated

Wealthy Americans have seen major growth when it comes to educational attainment, but the poorest Americans still struggle to graduate.

You hear a lot about the financial ramifications of income inequality: difficulty saving, major gaps in overall wealth accumulation, and a shrinking middle class. But the gap between America’s richest and poorest families also has a major impact on the ability to achieve educational goals, which can create long-lasting and detrimental consequences for low-income families.

A recent study from the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education and the University of Pennsylvania Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy (AHEAD) took a look at the educational achievement of students aged 18 to 24 from different income brackets over the past 45 years. The researchers found that when it comes to completing higher-education degrees, the gap between the rich and the poor has actually grown significantly.

In 2013, Americans in the highest-income bracket, defined as those households that made over $108,650 in 2012, were more than eight times more likely to have graduated from a bachelor’s-degree program than the lowest-income Americans, defined as households that made less than $34,160 in 2012. In 1970, the higher-income group was five times more likely to have hit this educational milestone. The rate of bachelor’s attainment in the most well-off families has grown from about 40 percent in 1970, to just about 77 percent in 2013. In contrast, for students whose families fall in the lowest 25 percent of earners, attainment has barely risen, moving from 6 percent in 1970 to 9 percent in 2013. While many factors play a role in the faster pace of achievement growth for top earners, higher levels of college preparation and better financial resources certainly help.

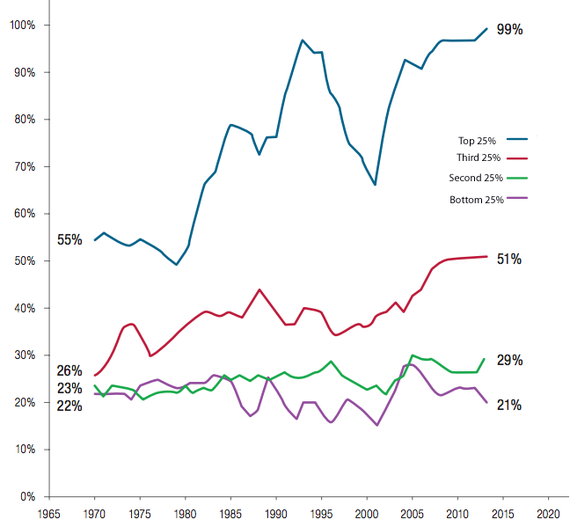

When you look at college-enrollment rate, the gap between the groups has actually gotten slightly smaller. In 1970, about 76 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 to 24 from the highest-income group participated in college compared to just 28 percent from the lowest-income bracket. By 2012, 81 percent of the richest young Americans were enrolling in college, and that number grew to 45 percent for the poorest group, the study shows.

But when it comes to actually graduating, the gulf between rich college students and poorer college students is wider than it was in 1970. According to the report, when looking at the wealthiest students who were enrolled in college in 2013, 99 percent graduated with their bachelor’s, up from 55 percent in 1970. But for enrolled students from the lowest-income group, attainment has stagnated, with just over 20 percent completing their bachelor’s—that’s about the same as what it was in 1970. A a 2008 report from the Pell Institute that looked into the decreased likelihood of graduation for low-income students found that these students are more likely to be older and live at home. Many are more likely to attend two-year colleges, and not transfer or attend another school in order to complete their bachelor's. They often have competing commitments, including family and job obligations that can take them away from school activities, making them more likely to drop out. They're also less likely to have financial support from their families.

Affordability is part of the issue. A 2014 report from the Government Accountability Office found that between 2003 and 2012, state funds for public colleges shrunk even as tuition climbed. The report from Pell Institute and AHEAD also cites similar issues that could contribute to the growing gap in higher-education. “The disinvestment of state funds for public colleges and universities occurring since the 1980s and the declining value of federal student grant aid have all aided in the creation of a higher education system that is stained with inequality,” write the co-authors Laura W. Perna, the executive director of AHEAD and Margaret Cahalan, director of the Pell Institute.

Researchers also reported that though the average cost of tuition and fees had more than doubled since 1970—from about $9,625 to $20,234 in the 2012-’13 academic year—the impact of the Pell grant, funds specifically awarded to low-income students, peaked in 1975, when the maximum award covered about two-thirds of average college costs.

In 2012, the maximum grant covered only 27 percent of the average cost of college. And unmet financial need—that is costs after discounts, grants, loans, and expected family contribution—for families in the lowest quartile was over $8,000, that’s double the amount on unmet need in 1990. This may also explain why Pell-grant recipients were likely to wind up with more student-loan debt than their peers, despite attending lower-priced colleges. At graduation, Pell recipients owed an average of $31,007 in 2012 versus $27,443 for non-Pell recipients.

These numbers, which show a widening chasm in educational attainment, are problematic because higher education is often touted as the most reliable vehicle for social mobility, and is generally the most recommended course of action for those trying to raise themselves out of poverty. A 2013 study from the College Board found that a college education was associated with higher earnings, better benefits—like a pension and insurance—and healthier lifestyles. The study also found that a college education was helpful for climbing the socioeconomic ladder.

Many believe that the benefits of a more accessible college education are good not just for low-income families or individuals, but the country in general. As Perna argues, “Society as a whole also benefits when more individuals complete higher levels of education. When college attainment improves, the tax base increases, reliance on social welfare programs declines, and civic and political engagement increases.”

Yet the increasing financial burden of education makes the first task on the path to advancement a very difficult one for many to complete. That can mean that those from poorer families—who are most in need of the boost that college can provide—continue flounder when it comes to educational attainment, while those from more privileged families are able to advance more rapidly.