The following has been adapted from Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties (Verso, 2016) and “‘Kill That Gook, You Gook,’ Asian Americans and the Vietnam War,” from The Global 1960s: Convention, Contest and Counterculture (Routledge, 2018, 217-235), by Karen Ishizuka. Ishizuka will serve on the “Unknown Stories: How We Shape Los Angeles” panel at the Global LA Summit on May 10.

_______________________

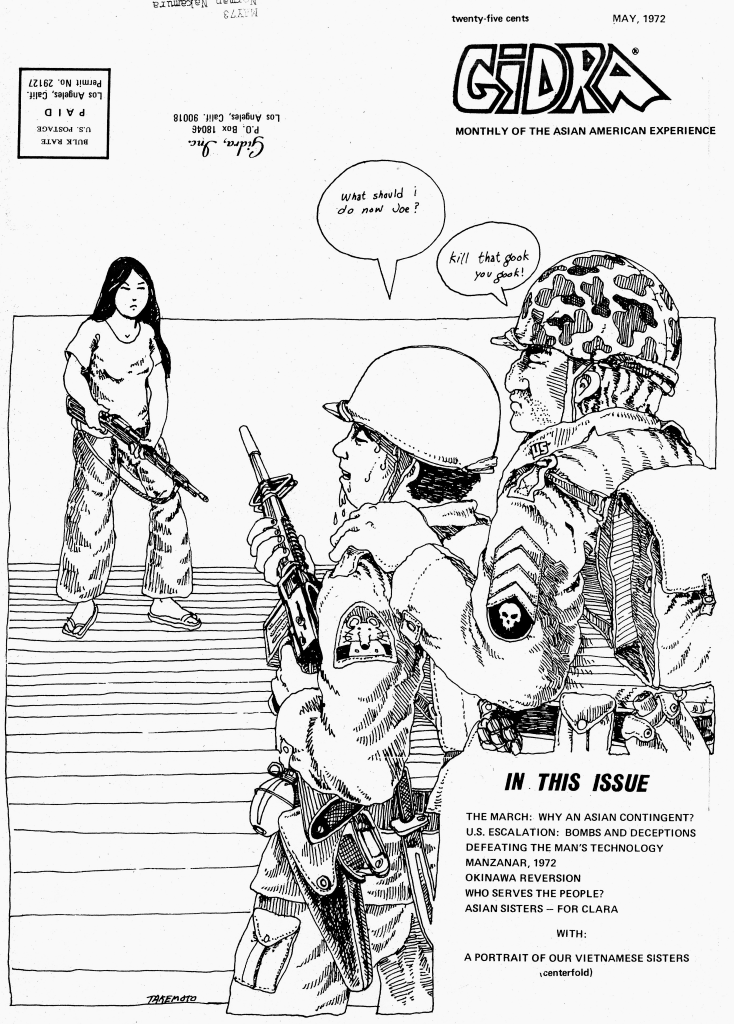

This penetrating cartoon of a white officer ordering an Asian American soldier to “Kill that gook, you gook!” hit at the heart of the singular experience that Americans of Asian descent faced during the 1960s: looking like the enemy. It appeared on the cover of the May 1972 issue of a small, volunteer, dissident newspaper produced in Los Angeles from 1969 to 1974 called Gidra: The Monthly of the Asian American Experience.

Although contemporary scholars have since written about the connection between the Vietnam War and the development of an Asian American identity, these concepts were first theorized in Gidra—published primarily by undergraduates who displayed what Raymond Williams called a diagnostic understanding of the situation in which they lived.

Currently, the term “Asian American” or “Asian Pacific American” is so common it has been neutralized into a mere adjective, barely more than a census label. But until the Vietnam War and the cultural revolution of the long Sixties, there were no Asian Americans. We were Americans of Chinese, Japanese, or Filipino ancestry, the ethnicities that constituted the majority of Asians in the United States at that time.

We were non-white, and therefore subject to the dominance of whiteness. Yet neither were we black, which—in a society that was defined in black and white—rendered us inconsequential. And while we were Americans—by 1975 almost 80 percent of Japanese-Americans and roughly 50 percent of Chinese and Filipino Americans were born in the United States—we were not seen as such. We were considered “Orientals,” foreigners in our own country.

This instantiation as both adversary and citizen led to an examination of the war from an Asian American perspective which in turn strengthened the formation of a distinctly political identity as Asian Pacific Americans.

Then, during the Vietnam War, we looked suspiciously like “gooks,” the epithet that associated all Asians with the enemy. This instantiation as both adversary and citizen led to an examination of the war from an Asian American perspective which in turn strengthened the formation of a distinctly political identity as Asian Pacific Americans. The construction of such a pan-Asian American identity was a mechanism and by-product of Asian Americans organizing in the Global Sixties and thereby never meant to be a synonym for common heritage or even racial pride.

One of the key players in both providing an Asian American analysis of the war and cultivating a pan-Asian political identification was Gidra. Through political cartoons, coverage of events that went unreported in the mainstream media, incisive commentary, and probing art and poetry, Gidra conveyed—even as it vetted and incubated—a particularly Asian American epistemological understanding of the Vietnam War.

In the June/ July 1970 issue, Gidra published one of the first articles to report on the anti-Asian xenophobia of the war. It was written by Norman Nakamura who had recently completed a tour of duty in Vietnam. His essay detailed rampant racist attitudes and incidents that were heaped upon Vietnamese women, children, and the elderly. Nakamura added that such behavior was not only widespread, it was condoned, because U.S. soldiers were taught that the Vietnamese were not people but “only gooks.”

The perils of looking like the enemy were also extended to American soldiers of Asian descent fighting for the United States on the front lines.

As the piercing cover of Gidra created by Alan Takemoto incisively asserted, the perils of looking like the enemy were also extended to American soldiers of Asian descent fighting for the United States on the front lines. Gidra published former Marine Mike Nakayama‘s testimony at the Winter Soldier Investigation held in January 1971 in Detroit. Nakayama testified that during basic training, he was told to “Stand up! Turn around so everybody can see you!” To the rest of the men, the drill instructor announced, “This is what a gook looks like!”

Within a year, Nakayama would be awarded a Bronze Star and wounded twice. The second time he was shot, he lay in a dirty cot in a military hospital with an open chest wound and shrapnel in his skull. Realizing that other U.S. soldiers with less severe wounds were getting treated while he lay there, he managed to utter, “Hey man, when’re you going to deal with me?” The answer: “Oh, you can speak English? Why didn’t you tell us you were an American? We thought you were a gook.”

Gidra reported on other events that received little attention from other alternative newspapers while being virtually absent in the mainstream media. For example, in May 1971, Gidra reported on the Anti-Imperialist Women’s Conference in Vancouver and Toronto that brought six women from war-torn countries in Southeast Asia to meet with hundreds of women from North America in an effort to end the war. Asian American veterans were invited to meet with the Southeast Asian women and provide security.

Through direct engagement with the concrete social and political issues about which they wrote, lived, and envisioned, Gidra brought previously unheeded questions of race and racism to the nationwide antiwar movement, which in turn cultivated the construction of a specifically political Asian American identity.

In July and August 1972, Gidra reported on the Emergency Summit Conference of Asian, Black, Brown, Puerto Rican, and Red People in Gary, Indiana, the first national gathering of activists of color against the war. Other coverage included the Vietnam Medical Supply Drive initiated by Asian American Vietnam War veterans to send medical supplies to Vietnam, the brutal assassination of foreign student Nguyen Thai Binh for his anti-war activities, and nationwide Asian American marches and rallies against the war.

Asian American Studies Professor Elaine Kim noted that because we had been historically defined by race, it was not difficult for many of us to respond to the racial character of the war in Vietnam. In addition, those of us who were Baby Boomers had literally grown up and come of age with the Vietnam war. In the January 1973 issue, staff writer Bruce Iwasaki wrote:

"The U.S. involvement in Vietnamese affairs began around the time we were born; stayed hidden from the national consciousness during our years of innocence; escalated as we matured; and has reached climactic proportions while our generation gains the will and seeks the means to end that involvement. Much as we forget, ignore, or grow numb to it, the war has been a constant shadow in our lives."

Iwasaki, who is now a Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge, not only spoke for our generation, he articulated the intersection of the global on the local while precisely and poignantly locating our loss of innocence:

"When we probed the roots of the war, we discovered more than the Pentagon Papers sequence of governmental deceit. We also discovered the Empire, its rulers, their methods—all at once."

The far-reaching consequence of this insight was his simultaneous understanding that this devastating realization contained the seed of political maturity, which strengthened the political consciousness of being Asian Pacific American:

"The Vietnamese have stripped the emperor’s clothes. They have opened our eyes to our genocidal past, our bloody present, and future potential of our own liberation. By forcing us to see what we really are, Vietnam’s revolution lets us seize the possibility of our own."

Russell Leong put forth the concept of “lived theory” that emerges from “work and working with others.” Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua called it “theory in the flesh,” which prioritizes “flesh and blood experiences.” Through direct engagement with the concrete social and political issues about which they wrote, lived, and envisioned, Gidra brought previously unheeded questions of race and racism to the nationwide antiwar movement, which in turn cultivated the construction of a specifically political Asian American identity.

Such knowledge only makes itself visible when we look deeply into the ways in which disenfranchised communities actively participate in the making of their own histories. Gidra stands as an example of how a small social movement newspaper not only promoted social change but developed theory as well.

_______________________

Karen Ishizuka is the Chief Curator at the Japanese American National Museum. She will serve on the “Unknown Stories: How We Shape Los Angeles” panel at the Global LA Summit on May 10.

Photo credit: Robert A. Nakamura/Visual Communications Photo Archive. The photo shows Mike Murase, one of the founders of Gidra and organizers of the first Asian American Anti-Vietnam War March in Los Angles’ Little Tokyo on May 11, 1972.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.