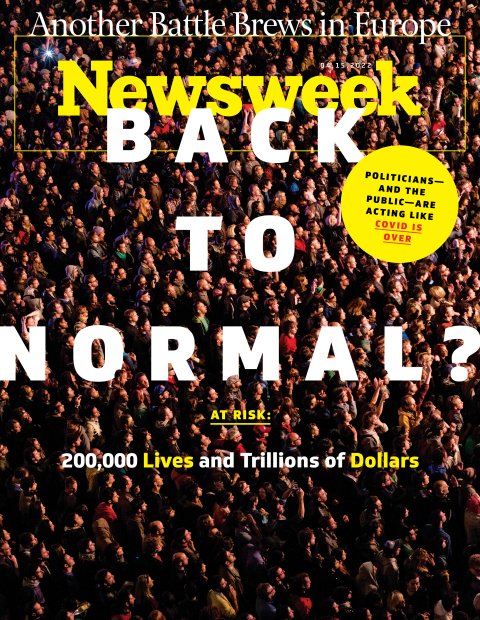

Everywhere you look, people are coming out from under their pandemic rocks. The masks are off, the bars are crowded, the kids are back in school. Even New York City, home to some of the most stringent mandates, no longer requires proof of vaccination in restaurants or masks in schools. On April 7, the Red Sox and the Yankees will square off on Opening Day in front of a potential crowd of 50,000-plus fans eager to cheer full-throated and (mostly) maskless into the breeze.

Baseball fans aren't the only ones yearning to put the pandemic behind them. So, apparently, is Congress. New spending on testing, vaccines and therapeutics has been harder to find than Putin's conscience. Senator Mitt Romney led the charge to whittle White House requests from $30 billion down to $16 billion before settling this week on $10 billion, to be repurposed from unspent COVID-19 relief funds. "While we have supported historic, bipartisan measures in the United States Senate to provide unprecedented investments in vaccines, therapeutics, and testing," he wrote in a letter to President Joe Biden, "it is not yet clear why additional funding is needed." (Emphasis added.)

While Congress fiddles, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that has killed more than a million Americans and as many as 18 million people worldwide so far, according to one estimate, is still at large. Europe's relaxation of pandemic restrictions, together with a more contagious variant of Omicron, BA.2, has triggered a rise in cases and an uptick in the U.S. is expected over the next few weeks. It isn't expected to cause a rise in hospitalizations and deaths in the U.S., but that's not certain.

Beyond the variant du jour are more fraught questions: Does the coronavirus have more surprises in store in the months ahead? Will a new variant come along that evades the protection of vaccines and prior infections and sends this weary nation back into the pandemic doldrums? Scientists have no answers.

Last month, while Russia's invasion of Ukraine dominated the news, a committee of two dozen or so scientists, doctors and public health experts released a report that lays out possible scenarios for the next 12 months. If the coronavirus winds up staying mild and doesn't get much more contagious, deaths may be as low as 15,000 to 30,000. If we're unlucky, a deadly new variant that can evade immune protections could raise the death toll significantly—in this scenario, the group projects casualties of 100,000 to 300,000 lives in the next 12 months.

The wide range in casualties for the worst-case scenario roughly corresponds to how well the nation handles another outbreak, says Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota and a contributor to the report. The fate of 200,000 lives could hang on whether the U.S. has a well-funded plan in place, with enough tests, antiviral medications and vaccines for all, or succumbs to the politics of fatigue and pretends the pandemic is over.

"It's very clear that any investment we make right now in terms of improving our ability to respond to this virus will save us a lot later," says Osterholm. "The more we invest, the lower the number of deaths will be. There's no question about that."

Which way the virus goes—whether it fades away or returns with a vengeance—is uncertain. It's clear, though, that assuming the rosiest scenario without planning for the worst is foolhardy. That is especially true in light of our history with this coronavirus, which turned more deadly in the Delta surge last summer and more transmissible when Omicron hit in January. "Anyone who has any experience with infectious diseases would have to tell you, 'don't bet against this virus,'" says Osterholm.

The longer-term worry is that the nation will forget the miserable performance of its public health system in the last two traumatic years and acquiesce to the status quo. What's needed is a public health overhaul that brings the U.S. up to the level of other advanced nations. Such an overhaul would act as an insurance policy against not just the COVID-19 pandemic but against other biological threats as well—both infectious diseases that emerge from the wild and potential lab-made pathogens intended as weapons, a threat that has grown more likely in recent years by startling advances in low-cost methods of genetic manipulation.

The price tag of such an overhaul would be far steeper than the few billion dollars Congress and the White House have been fighting over. It would cost an initial outlay of $100 billion in public health infrastructure spending, according to the report, and then $20 billion or so a year to maintain readiness.

If $100 billion sounds like a lot of money, it's chicken feed compared to the cost of doing nothing.

Budget Fights

The wrangling between the White House and Congress over COVID-19 spending has had nothing to do with any $100 billion long-term wish list. Rather, the Biden administration has wanted a more modest amount to keep ongoing pandemic programs running. Those include money to buy booster shots, develop an Omicron-specific shots, reimbursements for treatments, testing and antiviral medications, maintaining testing capacity and investing in a coronavirus vaccine that might someday work broadly against any variants the virus can produce.

COVID-19 may not seem urgent now. Levels of virus in circulation are low. Fewer than a quarter-million Americans are were infected in early April, and deaths had dropped below 800 per day versus more than 4,000 at the peak in January 2021. The BA.2 variant of Omicron, which is causing an uptick in Europe and in parts of the U.S., isn't expected to have a marked effect on hospitalizations and deaths in part because it's less virulent than Delta and many people have immune protection from vaccination and prior infection.

As we know from the past two years, COVID-19 infections tend to ebb and flow, with peaks followed by troughs and new peaks. If SARS-CoV-2 doesn't throw any new variants our way, it stands to reason that those waves would get successively smaller, as the virus finds fewer and fewer "naive" people—those without any immunity—to infect.

Many things can throw this rosy scenario off. For one, the protection offered by vaccines tends to wear off over time. Exactly how much isn't clear, but one study suggested that 95 percent protection degrades to about 78 percent over four or five months. That's still good protection for most healthy people, less so for the elderly and immunocompromised.

Another confounding factor is the virus itself. SARS-CoV-2 has shown a surprising ability to adapt to changing circumstances in ways that spell trouble. The notion that the coronavirus will gradually become more benign until eventually it's just an annoyance like the common cold is a myth. The only thing that matters to a virus, from the standpoint of evolution, is survival—its own. As long as killing more people doesn't interfere with its own ability to spread, the virus remains indifferent and could grow more virulent.

In the beginning of the pandemic, scientists may have given the public the impression that the coronavirus does not mutate very much, creating an expectation that the threat would not change over time. And at first, that appeared to be true. SARS-CoV-2 was so completely new to humans that it was able to spread unfettered through the world population. When an infected person came into contact with 100 people, the virus could in principle spread to each one of them.

As people acquired immunity to the virus, through vaccines or prior infection, the virus began running into roadblocks. If an infected person meets 100 people but half of them are immune, the virus has half the opportunity to spread. Suddenly, variants that are more efficient at jumping from person to person have a big advantage. That's what happened when Delta began to dominate in the latter half of 2021. It was able to produce more copies of itself than its predecessor, and those copies tended to collect in high concentrations in the nose and mouth. Each time an infected person breathed out, more virus particles were carried by tiny air currents out into the room. This enhanced "viral load" helped Delta spread more efficiently and also made it deadlier.

Crucially, killing more people didn't affect Delta's ability to spread. A characteristic of COVID-19 is that those who are infected walk around for a long time spreading the virus before they develop symptoms that send them to bed or to the hospital. "The moment of high virulence for COVID-19 comes very late in the infection, usually a lot later than the typical transmission time," says Peter Markov, an evolutionary virologist at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre in Ispra, Italy. "If an infected person has already infected 100 others, it doesn't matter from the standpoint of the virus if that person then dies." A similar dynamic is found in other viruses, such as HIV, Hepatitis-C and influenza. "With Hep C, you can be infectious and die 20 years later of liver cancer," he says.

Omicron superseded Delta for two reasons. First, it was far more transmissible. Whereas Delta tends to infect deep in the lungs, Omicron stays high in the throat, which makes it easier to escape through the mouth and nose. (The BA.2 variant of Omicron is 30 percent more contagious still.) Thankfully, this feature happens to make it less virulent than Delta. The next variant won't necessarily follow this trajectory.

The second reason for Omicron's success is its skill at evading immune protection, compared to Delta. As more and more people get immunity to the coronavirus, the variants that wind up succeeding are more likely to be those that developed ways of getting around that immunity.

Every time the virus makes copies of itself in the body of an infected person, it spins off mutation after mutation, searching for the one that is better adapted for the current environment. (Omicron is thought to have been gestated in the body of someone with a compromised immune system, which gave the virus time to spin off mutations.) Going forward, the more opportunity the virus has to replicate, by infecting many millions of people for long periods of time, the more likely it is that we'll see vaccine-resistant strains. Even this late in the pandemic, the coronavirus virus still has plenty of genetic possibilities—new ways of mutating—to adapt to its environment.

"It's like a slot machine," says Markov. "The more you pull the handle, the higher the chance that you'll get four apples—something beneficial for the virus that we don't like. The larger the number of these viruses, the higher the chance we have of a bad combination of mutations."

In recent months, the virus has revealed a new technique for morphing into new forms. It has shown a propensity for making "reassortants"—a combination of two different viruses that swap genetic material. That gave rise a few months ago to "Deltacron"—a combination of Delta and Omicron. That particular variant didn't get very far, but it demonstrated still another avenue the coronavirus has or producing troubling spinoffs.

How long vaccine protection lasts is closely related to how much virus continues to circulate. "There are now more people who have immunity or at least some kind of immunity," says Osterholm, "but I don't know what the variants or reassortants are going to do, and I don't think we have a clue yet what long-term durable immunity means."

As long as the virus poses a threat, letting down our guard is unwise, says Vivian Riefberg, a business professor at the University of Virginia's Darden School of Business. "It is absolutely idiotic to say all of a sudden, it's no longer raining, so I think I won't have a roof over my head."

The Price of Complacency

The short answer to Senator Romney's question—why is more spending needed?—is that SARS-CoV-2 may still have some ability to set the world back on its heels. What this means, in purely economic terms, is that $10 billion is by comparison a paltry expenditure, and even a $100-billion overhaul may be a bargain.

There are many ways of estimating the cost of a pandemic. The most obvious is its toll in human lives. More than six million people worldwide are known to have died from the coronavirus, and the true figure may be much higher. A group of scientists gathered data on "excess deaths"—the number of deaths that have occurred over and above what would otherwise be expected—in nations around the world for 2020 and 2021 and used computer models to estimate the true death toll of COVID-19. The study, published in March in The Lancet, a medical journal, concluded that the human cost of the pandemic is closer to 18 million deaths worldwide.

In the U.S., the count of COVID-19 deaths comes to nearly one million. The Lancet study estimates that deaths attributable to the pandemic were 31 percent to 44 percent higher still.

Most people may think of a human life as invaluable, but economists who work for the U.S. government can't afford that luxury. To them, the "economic value of a statistical life"—the contribution an average person makes to the economy in a lifetime—comes to about $10 million dollars. By that grim accounting, one million lives lost to COVID-19 amounts to a $10 trillion loss in productivity to the U.S. economy.

What does that astonishingly high number tell us about the next chapter of the pandemic? One clue lies in the comparative performance of nations in handling the past two years of the pandemic. For each 100,000 people, the U.S. has lost 294 to COVID-19. By contrast, Norway lost 44, Israel lost 116 and the U.K. lost 246. If the U.S. had done as well as the U.K.—which didn't do particularly well, either—159,000 fewer people would have died.

There are other ways of looking at the pandemic's impact on the economy. For instance, the U.S. gross domestic product is $2 trillion to $3 trillion smaller than it might have been had the pandemic not occurred, estimates Anton Korinek, an economist at the University of Virginia. (He arrived at this figure by extrapolating the growth of GDP before the pandemic.) The management consulting firm McKinsey arrived at $16 trillion in a July 2020 report. Whatever the accuracy of these methods, it's obvious that the cost is large. "What is the cost of economic decline?" asks Riefberg, who was an executive at McKinsey when the report came out. "You don't have to have a perfect model to know that it's in the trillions."

These calculations do not capture many intangible costs, of course. They don't take into account the suffering of millions of people who survived long hospital stays, sometimes on ventilators or the toll on their families. Nor do they include millions more long-COVID victims who live with chronic ailments of the nervous system, heart and lungs. There's also the impact on job losses, children who missed out on school, rising drug addiction, mental illness, loneliness and stress on parents, children and caretakers.

What Is the Fix?

The U.S. health care system has many gaps, particularly from the standpoint of public health. Much of the responsibility for administering health care belongs with the states, which lends itself to a Balkanization of approaches. What's more, the system is weak at the center. Among the various federal entities, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the White House, lines of responsibilities are blurry and coordination is often lacking. The U.S. health care system is a disorganized patchwork.

One of the most glaring shortcomings is the lack of a disease-surveillance capability—the gathering of real-time data about disease outbreaks and using that information to make informed decisions. For instance, a rise in SARS-CoV-2 was recently detected in wastewater systems, which is considered a leading indicator for a rise in COVID-19 cases. The use of wastewater monitoring is a potential boon to infectious disease surveillance, and many states have taken it up. But there is no standard way to take the measurements and no nationwide, comprehensive system for gathering the information and analyzing it. The recent report, "Getting to and Sustaining the Next Normal: A Roadmap to Living with Covid," calls for building such an integrated system.

The lack of surveillance capability is why, throughout the pandemic, U.S. public health authorities were relying on data from Israel and the U.K., which both have better disease-surveillance systems than the U.S. does. It's also why so many studies of the coronavirus seemed to come from Israeli and British scientists, who can draw on a wealth of data that simply does not exist in the U.S. Relying on other nations was useful, to a point, but without such a system in the U.S., public health authorities had little information on the disease's progress at home. "If you don't have the data, and a common way to analyze it, you're often flying blind," says Riefberg. "You find out about the problem when everybody is rushing to the ER, as opposed to people saying, 'we see where this is going.'"

The only unequivocal success in the U.S. pandemic response was Operation Warp Speed, in which the government threw money at the pharmaceutical companies for vaccine development, guaranteeing a market for the mRNA vaccines even though nobody knew how effective they were going to be. The policy fell short, however, when it came time to administer the vaccines and so many people were reluctant to take the shots. Vaccinations are now tapering off even though only three-quarters of eligible Americans have gotten at least one shot, and less than a third have gotten booster shots. In some states, fewer than half of residents over the age of 65 have gotten boosters.

The lack of public buy-in for vaccinations is a public health failure. If many people are reluctant to accept vaccines and others don't stay up to date with their shots, the virus has more opportunity to try and hit the genetic lottery with a new variant. Like it or not, the battle against the evolving coronavirus—against any viral pathogen—is a never-ending war of measures, countermeasures and counter-countermeasures.

One lesson from the past two years is that education and outreach for vaccination should be a much bigger part of public health going forward.

Promoting vaccination is not simply a matter of making public-service announcements or launching social-media campaigns. The push to increase vaccination rates has to address the attitudes of myriad groups of people, shaped by their own histories. Religious people tend to take a fatalistic attitude toward illness. Black Americans tend to be skeptical of the medical establishment. Some people don't get vaccinated because they tend not to go to the doctor anyway, or because they're out of work and depressed, or because they can't afford medical treatment or have poor options for transport.

When a public health measure requires the participation of nearly everyone, what's needed, say behavioral scientists, are strategies and networks designed to reach them. Education may be an effective way to push back against the politicization of public health measures, which is a big factor in public resistance, says Dolores Albarracín, a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and a Roadmap contributor. It proposes more intensive education and outreach on public health.

"The K-12 system could be having more impact in making sure that by the time you get out of high school, you're a convert," she says. "Really changing the health education curriculum is long-term investment, but it's probably worth it. When the next pandemic comes, you'd have a population that understands what a virus is. This is a way to push back against the politicization of public health."

The Roadmap report includes other reforms that would have helped greatly over the past two years and could help cope with the next outbreak. The committee suggests improving ventilation in schools, which could cut down on illness from COVID-19 and other respiratory diseases. It includes a system of monitoring and coordinating hospitals to avoid overwhelmed emergency-rooms. It includes many steps designed to avoid lockdown measures when outbreaks occur, steps to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. A well-functioning pandemic response would serve as a hedge against bioterrorism, which grows more likely each year, experts say.

After two years of fretting over an invisible virus and avoiding contact with friends, neighbors and loved ones, it's natural to want to put the pandemic to rest. But ignoring the current catastrophe is a recipe for more of the same.

"There's this desire to think that the pandemic is over and everything's going to be great, and therefore we don't need to spend any more money because there aren't going to be further problems," says John Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College.

"Well, yeah, maybe. And maybe not."