Growing up in Southern California, Ryka Aoki dreamed of being a writer, but her Japanese American parents expected her to study the sciences or something technical.

Her father, a mechanic who hailed from Hawaii’s Big Island, asked her if she knew of any Asian writers, and admittedly she didn’t. “My parents told me writers don’t make money,” she told NBC Asian America.

So Aoki acquiesced and studied chemistry at the University of California, Los Angeles, becoming the first person in her family to graduate from college.

She later became a prolific and award-winning writer, publishing “Seasonal Velocities,” a collection of poems, stories and essays, the novel, “He Mele A Hilo,” the poetry book, “Why Dust Shall Never Settle Upon This Soul,” and the children’s book, “The Great Space Adventure.”

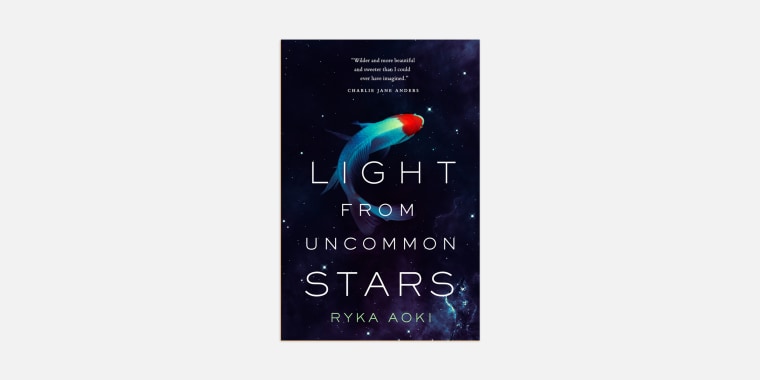

Aoki’s latest work, the critically acclaimed science fiction and fantasy novel “Light From Uncommon Stars,” follows the intertwined lives of three Asian American women: Katrina Nguyen, a young transgender runaway; Shizuka Satomi, a violin teacher who made a deal with the devil; and Lan Tran, a retired starship captain and interstellar refugee who runs a doughnut shop with her family.

Packed with meditations on music, identity, found family, immigrant culture and redemption, the book is set in the Asian American enclave of the L.A.-adjacent San Gabriel Valley, where Aoki, who is trans, was raised, and weaves a story that’s joyfully queer.

She said if she had a book like this when she was younger, she would have fought her parents and been a writer from the start. “I would have had heroes,” said Aoki, who learned to play the violin in order to write about the instrument. “I would have probably not been so miserable.”

After college, she spent a year drifting and worked as a technician in an environmental lab where she did things like analyze toxic waste. She felt depressed and would collect college maps because she was “dreaming to be out of there.”

In the meantime, Aoki took a playwriting course, wrote poetry and scored part of a rock opera. She applied to numerous master of fine arts programs, only to be rejected by them all. The same thing happened the following year.

But on her third attempt, Cornell University offered her admittance and financial assistance to its creative writing program. “What Asian parent is going to argue with an Ivy League school paying their [child’s] way?” she said.

She said people didn’t understand her work because it was written from an Asian perspective.

“I could write about my breakfast in my Cornell workshop and they would think I was discussing the Vietnam War and that’s not an exaggeration,” she said. “There was still a lot of novelty to having an Asian writer there, but they didn’t quite know how to take care of us yet.”

While there, Aoki — a former judo junior national champion — served as head instructor of the Cornell Judo Club.

For the past 10 years, she has directed Supernova Martial Arts, a self-defense and martial arts program, now at the Trans Latin@ Coalition in Los Angeles, and has taught seminars throughout Southern California.

“Teaching self-defense is how I feel I give directly back to the community,” she said. “I feel that everybody deserves as much safety as possible, but a lot of self-defense classes when I started out had been taught by cisgender people who didn’t understand the various issues that a trans woman will face, even the type of violence, which is completely different.”

Aoki, who has been an English professor at Santa Monica College for 20 years, came to judo around age 9. “I was a little Asian kid who didn’t know how queer she was,” she said. “When I was growing up, I never knew how to relate to people; I was lacking a bit of an owner’s manual.”

She learned what she was experiencing was gender dysphoria and later transitioned. She said she realized Asian Americans weren’t always accepting of members of her community.

Aoki said she has seen Asian parents in the U.S. disown their queer and trans children. “There’s a lot of people who are so afraid of what their neighbors are going to think that they turn their own children out and that’s insane,” she said.

She also believes that members of the Asian American and the Pacific Islander queer community can do better when it comes to solidarity with other marginalized groups.

“We can still as Asians and queer be horribly racist, horribly anti-Black, horribly anti-brown,” Aoki said. “We’ve been through a lot as Asians, but that doesn’t give us the privilege, license, to turn off our compassion, our empathy, our love for our fellow humans who have suffered, suffered, suffered, suffered. Being racist isn’t going to bring us any closer to our parents — not in a good way.”