Experts warned of a pandemic decades ago. Why weren't we ready?

In a rueful look back at her prescient book, an author wrestles with why we shrugged at the nightmare warnings and hopes this time will be different.

In my obsessive reading about the coronavirus pandemic, I’ve avoided articles that focus on the early missteps that could have stopped COVID-19 if only we’d been more attentive, organized, and responsive. Those articles were wreaking havoc with my anxiety level. The time for “coulda, woulda, shoulda” would be later, I figured; what matters now is whatever needs to be done in the next few days, and the next few days after that.

There’s also a personal reason why I’ve boycotted articles about early warning signs: Scientists were detailing those early warning signs decades ago, and a handful of science journalists were writing about their work. I was one of those journalists.

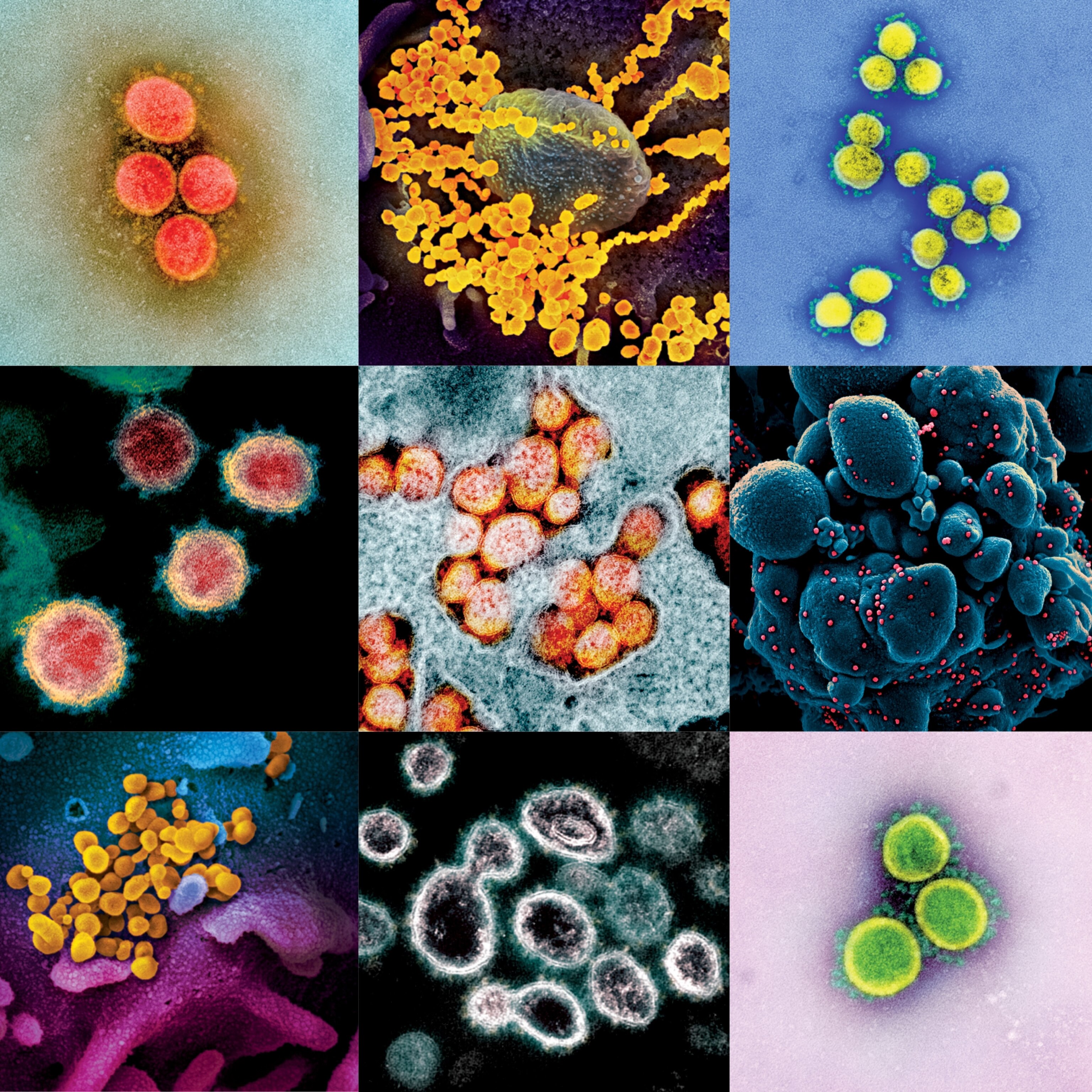

When I started researching A Dancing Matrix in 1990, the term “emerging viruses” had just been coined by a young virologist named Stephen Morse, who would become the main character in my book. I wrote about how experts were identifying conditions that could lead to the introduction of new, potentially devastating pathogens—climate change, massive urbanization, the proximity of humans to farm or forest animals that serve as viral reservoirs—with the worldwide spread of those microbes accelerated by war, the global economy, and international air travel. Too many of us, I wrote, were blithely going about our business despite the growing threat. Sound familiar?

“The single biggest threat to man’s continued dominance on the planet is the virus.” I used that searing quote from Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg, who was president of Rockefeller University and Morse’s boss, in the introduction to my book. Back then I thought it was a little bit melodramatic. Now it strikes me as terrifyingly accurate.

The other day, I phoned Morse to see how he’s holding up. He’s a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and in the age range of the most vulnerable now, he told me. (I am, too.) He and his wife are self-quarantining in their apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side.

“I’m discouraged, yes, to find we’re not better prepared after all this, and we’re still deep in denial,” Morse said. He went straight to a favorite quote, from management guru Peter Drucker, who once was asked, “What is the worst mistake you could make?” His answer, according to Morse: “To be prematurely right.”

But Morse and I didn’t get it exactly “right,” of course, prematurely or otherwise. Nobody did. When I was asked on my book tour what the next pandemic was likely to be, I replied that most of my sources said it would be influenza.

“I never liked lists,” Morse told me now, adding that he always knew the next plague could come from anywhere. But in the early 1990s, his colleagues did tend to focus on influenza, so I did, too. Maybe that was a mistake; telling people the next pandemic would be caused by influenza didn’t make it seem nightmarish at all. The flu? I get that every year. We have a vaccine for that.

So maybe the warnings were too easy to dismiss as “just the flu”—though I insisted, throughout my book and every time I talked about it, on calling the virus by its full name, influenza, to strip it of any possible familiarity. Maybe my book was too obscure, or I should have worked harder to promote its message. Maybe I should have stayed on the emerging virus beat instead of wandering off to write about so many other things.

But other journalists also were writing books with the same message. Some of them were huge bestsellers; I used to jokingly refer to mine as the “prequel” to the books that made a mark just a year later, The Hot Zone by Richard Preston and The Coming Plague by Laurie Garrett. (More recently there was another bestseller, Spillover by David Quammen, a follow-up to a story he wrote about emerging diseases for National Geographic in 2007.) All of them describe the same dire scenarios, the same war games, the same cries of being woefully unprepared. Why wasn’t any of that enough?

There’s a strange vertigo induced by watching this unfold nearly three decades after I wrote that it would do so in pretty much the way it’s happening.

One of the scientists in my book, Edwin Kilbourne, might have had something to say about that. Kilbourne, a leading influenza vaccine researcher, was gaunt and goateed; after I met him in his office at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in his white lab coat, I described him as a cross between Pete Seeger and Jonas Salk. (Only after he died years later at the age of 90 did I realize how close to the mark I’d been. His 2011 New York Times obituary mentioned that besides being an influenza expert, Kilbourne was a published poet—though, unlike Pete Seeger’s, his poetry ran to doggerel. The obit quoted one couplet, about a bighorn ram: “His wooly wooing is neither smooth nor is it unctuous/And therefore can be fairly termed rambunctious.”)

In the mid-1980s, Kilbourne was asked to participate in a conference at the Banbury Center on Long Island about “Genetically Altered Viruses and the Environment.” He used it as a chance to imagine a true nightmare virus with all the qualities that would make it most contagious, most lethal, and most impossible to control. He called it the "maximally malignant (mutant) virus," or MMMV. As Kilbourne described it, MMMV would have the environmental stability of poliovirus, the high mutation rate of influenza virus, the unrestricted host range of rabies virus, and the long latency potential of herpes virus. It would be transmitted through the air and replicate in the lower respiratory tract, like influenza, and it would insert its own genes directly into the host’s nucleus, like HIV.

This novel coronavirus isn’t Kilbourne’s ghoulish MMMV, exactly, but it does have a lot of its scariest properties: It’s transmitted through the air, lasts days on countertops, and replicates in the lower respiratory tract. On top of that, people can have mild or asymptomatic cases, meaning that, even though they are infectious, they often feel healthy enough to walk around, go to work, and cough on us.

But just as Morse says he’s never been a fan of “Most Likely to Endanger Us” lists, Kilbourne told me 30 years ago that he wasn’t trying to make precise predictions with his MMMV presentation, either. His point, he told me, was to demonstrate that “with viruses, in which only a few changes can make a huge difference in the way the microbes behave, trying to predict the paths of evolution and emergence can be a treacherous affair indeed.”

And now, in this moment of waiting for other shoes to drop, musing on why the warnings went largely unheeded, I find myself returning to one sad sentence I wrote in A Dancing Matrix: “Ask a field virologist what constitutes an epidemic worth looking into, and he’ll answer with characteristic cynicism, ‘The death of one white person.’ ”

To my regret, I can’t find my notebooks that might have the name of an actual “field virologist” who said that to me. Someone must have told me that and must have said it cynically. Still, I do believe, based on our slow collective response to so many of the outbreaks we’ve seen in the past three decades, that this sense of other-ing has been at the root of much official, as well as personal, complacency about new viral plagues.

Maybe we were inured to the real threat of a true international crisis because we saw so many “This Is The Big One” threats end up flaming out, as one after another outbreak remained confined to regions of the world that felt remote and different from most of us. Except for AIDS, raging epidemics have tended not to go global: SARS in 2003 pretty much stayed in Asia, MERS in 2012 didn’t really leave the Middle East, Ebola in 2014 was mostly an African scourge. In the rest of the world, we kept watching ourselves dodge a bullet, and it was easy to attribute everyone else’s susceptibility to things that didn’t exist in our comfy way of life. Most of us didn’t ride camels, didn’t eat monkeys, didn’t handle live bats and civet cats in the marketplace.

The same year I published my book, Morse published an edited volume of academic papers called Emerging Viruses. Lederberg made an appearance in the book. “Some may say that AIDS has made us ever vigilant for new viruses,” Lederberg wrote. “I wish that were true. Others have said that we could do little better than to sit back and wait for the avalanche”—and by “others,” Lederberg wrote, he meant policy makers, the general population, and even “the major health establishments of the world.” He was amazed that people still insisted on blinders “even to this day,” despite the growing threat of new viral diseases.

He wrote that 30 years ago. What would he think of us now?

Going back over this same territory with an urgent sense of menace is painful indeed. There’s a strange vertigo induced by watching this unfold nearly three decades after I wrote that it would do so in pretty much the way it’s happening. If I had made the case for surveillance and preparation more forcefully back then—that is, if I had written a better book—would we be here now?

People have been offering all kinds of thoughts about the origin of the current pandemic, from the predictable to the original. But right now, when each passing week seems almost unrecognizable, there’s something weird and maybe a little enlightening about reading stories from my book—stories that took place in the last century, when new viruses kept emerging, raging through a population, and eventually dying out. Never (with the exception of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic) on the scale we’re seeing now, and never with this ferocity and with this particular mixture of transmissibility and lethality. But we almost learned the right lessons in the 1990s; maybe we’ll learn them for real this time.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads