Assume a universe

This is a very thought-provoking essay from a couple of cosmologists about what may be a gathering intellectual crisis in cosmology, in terms of the so-called standard model of the universe’s history:

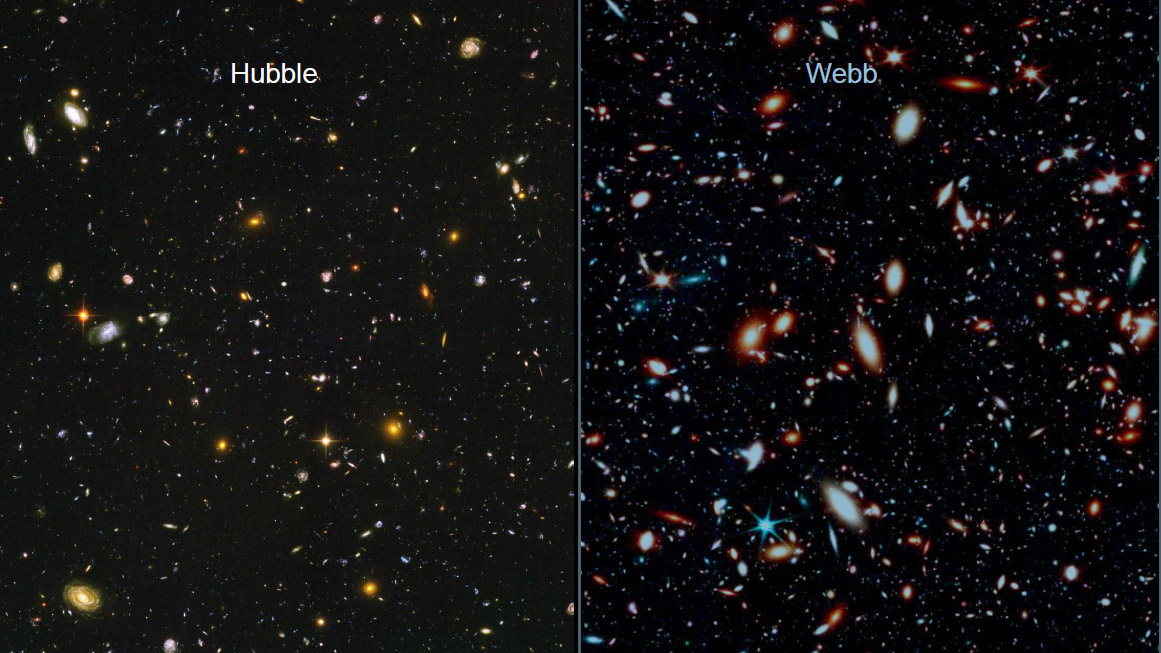

Launched at the end of 2021 as a joint project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, the Webb, a tool with unmatched powers of observation, is on an exciting mission to look back in time, in effect, at the first stars and galaxies. But one of the Webb’s first major findings was exciting in an uncomfortable sense: It discovered the existence of fully formed galaxies far earlier than should have been possible according to the so-called standard model of cosmology.

According to the standard model, which is the basis for essentially all research in the field, there is a fixed and precise sequence of events that followed the Big Bang: First, the force of gravity pulled together denser regions in the cooling cosmic gas, which grew to become stars and black holes; then, the force of gravity pulled together the stars into galaxies.

The Webb data, though, revealed that some very large galaxies formed really fast, in too short a time, at least according to the standard model. This was no minor discrepancy. The finding is akin to parents and their children appearing in a story when the grandparents are still children themselves.

It was not, unfortunately, an isolated incident. There have been other recent occasions in which the evidence behind science’s basic understanding of the universe has been found to be alarmingly inconsistent.

Take the matter of how fast the universe is expanding. This is a foundational fact in cosmological science — the so-called Hubble constant — yet scientists have not been able to settle on a number. There are two main ways to calculate it: One involves measurements of the early universe (such as the sort that the Webb is providing); the other involves measurements of nearby stars in the modern universe. Despite decades of effort, these two methods continue to yield different answers.

At first, scientists expected this discrepancy to resolve as the data got better. But the problem has stubbornly persisted even as the data have gotten far more precise. And now new data from the Webb have exacerbated the problem. This trend suggests a flaw in the model, not in the data.

Two serious issues with the standard model of cosmology would be concerning enough. But the model has already been patched up numerous times over the past half century to better conform with the best available data — alterations that may well be necessary and correct, but which, in light of the problems we are now confronting, could strike a skeptic as a bit too convenient.

Physicists and astronomers are starting to get the sense that something may be really wrong. It’s not just that some of us believe we might have to rethink the standard model of cosmology; we might also have to change the way we think about some of the most basic features of our universe — a conceptual revolution that would have implications far beyond the world of science.

I know absolutely nothing about the science behind these debates. That said, the whole dark matter/energy theory — the theory (hypothesis?) that 96% of the universe is made up of stuff we can’t observe, because it has to be, because otherwise the math doesn’t work — could, if one were of a skeptical disposition, sound like a sort of massive kludge, to save a broader theory that appears to have severe empirical issues.

The essay includes some fascinating speculations about what, as they say at the secret meetings of the Stonecutters, is really going on:

These rarefied issues don’t come up in most “regular” science (though one encounters similarly shadowy issues in the science of consciousness and in quantum physics). Working so close to the boundary between science and philosophy, cosmologists are continually haunted by the ghosts of basic assumptions hiding unseen in the tools we use — such as the assumption that scientific laws don’t change over time.

But that’s precisely the sort of assumption we might have to start questioning in order to figure out what’s wrong with the standard model. One possibility, raised by the physicist Lee Smolin and the philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger, is that the laws of physics can evolve and change over time. Different laws might even compete for effectiveness. An even more radical possibility, discussed by the physicist John Wheeler, is that every act of observation influences the future and even the past history of the universe. (Dr. Wheeler, working to understand the paradoxes of quantum mechanics, conceived of a “participatory universe” in which every act of observation was in some sense a new act of creation.)

I never expected the Godfather of Critical Legal Studies to show up in this sort of context, but I suppose no one ever expects the metaphysical inquisition. (Thanks I’ll be here all week).

All this reminds me of an extremely annoying recent interview, also in the NYT, with Daniel Dennett, the Godfather of the New Atheism. What bugs me about Dennett et. al. is the sheer insouciance of these types. Listening to Dennett, one would get the impression that human beings have now figured out about 98% of what’s to be learned about the nature of reality, with only a few minor side issues still up for discussion. That view strikes me as being as delusional as religious fundamentalism, and for pretty much exactly the same reason: the wholly unwarranted intellectual arrogance involved, given that our understanding of the most fundamental scientific matters is, in historical — let alone cosmological — terms, regularly subject to truly radical revisions (This is the idea at the core of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions).

Jorge Luis Borges has the last word on this subject:

Obviously there is no classification of the universe that is not arbitrary and conjectural. The reason is very simple: we do not know what the universe is. “This world,” wrote David Hume, ” … was only the first rude essay of some infant deity who afterwards abandoned it, ashamed of his lame performance; it is the work only of some dependent, inferior deity, and is the object of derision to his superiors; it is the production of old age and dotage in some superannuated deity, and ever since his death has run on … ” (Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, V, 1779). We must go even further; we must suspect that there is no universe in the organic, unifying sense inherent in that ambitious word. If there is, we must conjecture its purpose; we must conjecture the words, the definitions, the etymologies, the synonymies of God’s secret dictionary.