Emtithal Mahmoud wrote her first poem when she was 10 years old, about the genocide that took place in her home country of Sudan. Having been told at school that a poem rhymes and should be about something you care about, she titled it ‘War in Darfur’.

“For me, it was a fact of life that if you know what the cost of violence is, you must speak up about it and try to get as many people to understand as possible,” says the world champion slam poet, former refugee, and UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador. “Poetry is an incredibly visceral art form. It reaches people where they don’t expect to be reached and that’s why I like it; that’s why it’s useful. I choose poetry because it can be disarming and put things into perspective.”

Born in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum in 1993, Mahmoud emigrated to Philadelphia in the US with her parents when she was five, briefly returning to her home country a few years later when her mother and father were protesting against the government, which had stopped paying teachers. Always writing from a place of emotion, she is passionate about giving a human face to global issues, using the spoken word to drive people to action. “If you fully believe what you’re saying, and you stand behind it, people will feel that,” she says.

Even though the Darfur genocide was being covered widely by American media outlets, reaching the front page of The New York Times, the reality of those who died in the struggle was not. “All the numbers people were talking about, those were my family members, those were my cousins that I played with,” she explains. Throughout that time, the people who most supported Darfuris were those who had themselves endured significant hardship, including survivors of the Holocaust, the Rwandan war and the civil war in South Sudan.

She cites the relevance of the 1946 poem First They Came by Martin Niemöller, which talks about the consequences of not speaking up for others. “It ends: Then they came for me/ And there was no one left/ To speak out for me,” she relays. “If we don’t help others understand, we end up in a world where there’s no one left to fend for us.”

At just 29 years old, Mahmoud has achieved significant progress for Sudan, setting up the country’s first inclusive civilian peace talks in the form of Poetry Town Halls in 2017, and the following year, she embarked on a 1,000-kilometre peace walk from Darfur to Khartoum, with thousands of people joining her across the way.

Mahmoud first enraptured audiences across the globe with her own writing when she won the 2015 Individual World Poetry Slam Championship in Washington DC with her poem Mama, which she wrote just a few hours prior, shortly following the death of her grandmother. “That poem was part of my grieving process,” Mahmoud reflects. “It was almost like a send-off for my grandmother. It was hectic, it was painful, it was a relief, maybe all the stages of grief at once in a poem.” While she says that each of her poems contains a part of herself, she also believes that in the process of invoking someone’s name or their story, “you’re bringing a little bit of them in there too – that’s why Mama has a lot of power in it; not because I wrote it, but because it’s about someone so powerful.”

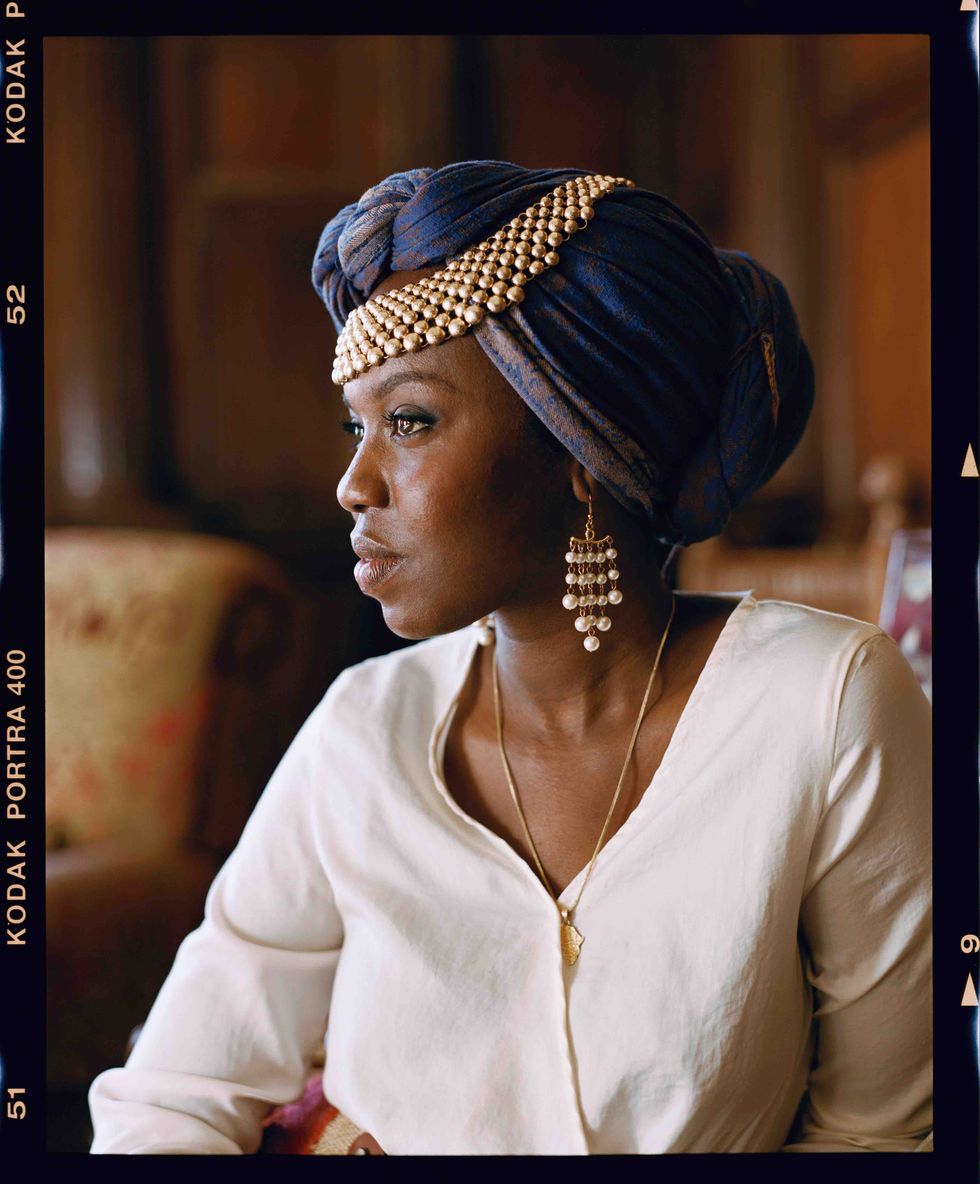

Since graduating from Yale in 2016, where she studied molecular biology and anthropology, she has taken part in a round-table discussion with Barack Obama on his visit to the Islamic Society of Baltimore, and has commanded some of the world’s largest stages. These include the UN General Assembly, the World Economic Forum in Davos and the Women’s Forum in Paris, where she is often the youngest person in the room. “Being a Black woman, being a former refugee, being a Muslim woman, being young, a poet, all those different things can be a little bit disarming because people will constantly underestimate you,” she says, “and in those moments, you’re able to surprise them in a really good way.”

At this year’s climate summit COP27, held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, Mahmoud will deliver her impactful poem, Di Baladna, which means Our Land in Arabic, inspired by conversations she had with refugees from Nigeria, Syria, Rohingya and from camps in Cameroon, Jordan and Bangladesh. “This year’s COP is an opportunity: we’re finally moving to a world where people not only think of animals and greenery when they think of climate, but they think of the people as well. It’s no longer a question of if marginalised voices or vulnerable populations will be included in the conversations, but a question of how.

“Weaving in the interviews was almost fulfilling a promise that I gave to the people I was talking to when they asked me, ‘Can you get this message out?’” While the poem is not explicitly about refugees, she explains that it’s about our world as a whole and things that she feels we need to work on. “It was really hard to think about what it was that I wanted to say. Do I approach it from a scientific angle or a personal angle? Do I talk about my experiences in Sudan, with all the flooding and the effects of drought? In the end it felt really good to try and unify all the different perspectives that I had, which we all might be able to resonate with.”

Indeed, Mahmoud’s ability to connect with others through words is an exceptional strength of hers, and one she will no doubt put to good use in her second book, a memoir, which she is currently writing. She is also applying to medical school, because in her words, “Medicine is where my heart is and always will be, and I think that I’ll be able to bring what I’ve learnt to expand the space of what I can do in medicine.”

Her greatest dream for the future is that one day her poetry will become a marker of how things used to be, “a relic of history”, as she says. But the sad reality is that even some of her oldest poems are increasingly relevant as time goes by. Yet hope resides in the form of her five-year-old sister, who Mahmoud says knows nothing of her family’s history. “She doesn’t know about the genocide, she doesn’t know that we are survivors, or that we are former refugees. She doesn’t have any understanding of that.” She continues, “To me that’s one of the biggest triumphs you can have towards erasure: the possibility of an entire generation who does not have to suffer as we suffered in the past.”

Above all else, Mahmoud’s ambition is to improve the lives of others, “to leave the world a little bit better than the way I found it”. Through her tireless work and moving words, she has surely made great strides in doing just that.

Watch Emtithal Mahmoud perform Di Baladna below: