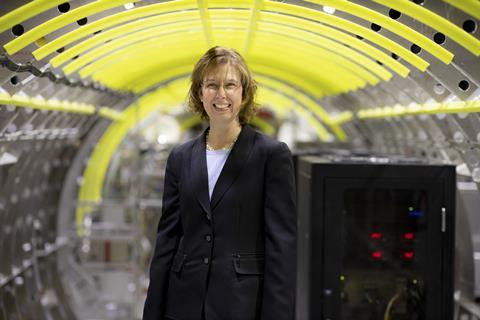

Gulfstream aerodynamics engineer Cathy Downen leads the airframer’s certification team - meaning she has the final say on what flies and what does not. She is also a firm defender of the ODA scheme

When Gulfstream’s Cathy Downen was a teenager, she often watched her father tinker in his workshop.

“He was an electrical engineer and he would design things on paper, little sketches,” says Downen. “And then he would build things, he would build a computer, all kinds of stuff.”

Once a year the family went to a local airshow.

“I was just enthralled with the grace, the power, everything that is an airplane,” Downen recalls. “At one of the shows, I asked my father, is there such a thing as an engineer who designs airplanes? And when he said, ‘Yes’, I was like, that’s it. That’s what I want to do.”

Two aerospace engineering degrees and three decades of aircraft design experience later, Downen leads some of the most crucial certification and airworthiness decisions for any new aircraft rolling off the Savannah-based airframer’s final assembly line.

She has been with the business jet manufacturer for 10 years, and currently directs Gulfstream’s type certification programmes, a job in which she has complete oversight of certification activities across the company.

“Whenever we have a new airplane design, or even a change to an existing design, we have to demonstrate to the regulatory authorities that it’s safe, and that it meets all of the regulations,” she says. “Our team is the interface between Gulfstream and those regulatory people to make sure that we’re doing everything necessary to show compliance for the aircraft.”

Downen also is Gulfstream’s Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) programme administrator, meaning she oversees aspects of certification work delegated to Gulfstream by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Airframers have largely credited self-certification programmes for enabling them to bring safe technologies to market faster.

But ODA - known by its detractors as “marking your own homework” - has been under scrutiny following two Boeing 737 Max crashes in 2018 and 2019. The accidents led investigators and lawmakers to criticise both the FAA’s delegation process and Boeing’s 737 Max design, with allegations that Boeing muscled the Max through certification despite internal concerns.

Though controversial, Downen says the authorisation is difficult to attain, and extremely valuable for both the company and the regulator.

“The FAA is very selective and careful about who they give that authority to,” she says, describing a year-long process she went through to get the qualification.

She adds that without delegating some of these responsibilities to experienced engineers like herself, the FAA would not have the resources to track and manage every aspect of every certification process in a timely fashion. That would delay programmes and increase cost.

Previously, Downen was Gulfstream’s programme manager for the G600, the airframer’s flashy next-generation super-large-cabin, long-range business jet that entered service in 2019. In that role, she oversaw the jet’s design, development, flight testing, certification, and entry into service.

“I am so very proud of that aircraft in particular,” Downen says.

The 19-passenger G600 has a range of 6,500nm (12,000km) and can reach Mach 0.925.

Working with the FAA on groundbreaking and innovative technologies can be challenging, Downen says. But the end goal is to build a safe and reliable aircraft. To achieve that, collaboration is essential.

“Often, our new technology has no regulations to govern it. So since we have a good relationship with the FAA we can work with them early to talk about… what we’re thinking about doing five to 10 years out, and start to work with them on what we need to do to show compliance for this type of new technology,” she says.

While her aerodynamicist credentials are impressive, actually piloting an aircraft is not for her.

“I took lessons while I was in college. And it turns out I’m a really bad pilot. I never got to solo because my instructor and I both agreed it was best that I just kind of walk away,” she says.

But her experience in the cockpit was invaluable as part of her engineering education, “to understand [an aircraft’s] handling characteristics, and what flaps do, and what it means to put your gear down and how it feels on the airplane”.

Throughout her aerospace engineering career, Downen was often the only woman in the room. When she spoke, heads turned.

“Being in an industry that is dominated by men can be intimidating, just even to say something in a meeting,” she says. “That took bravery in the beginning.”

As her responsibilities grew and she moved into leadership roles, she was coached to “be more like a man” – advice she promptly discarded. “I was told that would make me more successful and more useful. And each time I’ve pushed back and said: ‘That doesn’t work for me.’

“Women leaders are very different from men leaders, and sometimes the men are uncomfortable with that leadership style,” she says.

So as she mentors young women in her field, she gives them two critical pieces of guidance: speak up, and be different.

“At Gulfstream we value innovation, and innovation does not come from everyone thinking the same,” she says.

“Have confidence in what you know, and don’t be afraid to share it. Find your voice and don’t be afraid to use it.”