Editor’s Note: Renee Knake Jefferson and Hannah Brenner Johnson are the authors of “Shortlisted: Women in the Shadows of the Supreme Court.” Knake Jefferson is the Doherty Chair in Legal Ethics and Professor of Law at the University of Houston. Brenner Johnson is the Vice Dean and Professor of Law at California Western School of Law. The views expressed here are their own. Read more opinion on CNN.

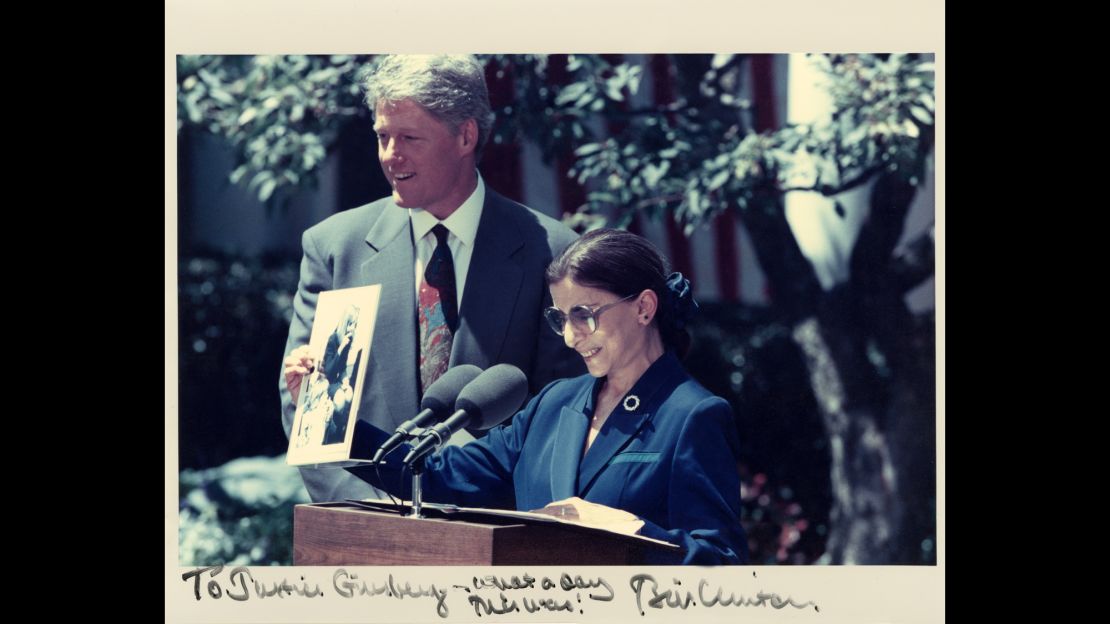

When President Bill Clinton selected Ruth Bader Ginsburg as the nominee from his Supreme Court shortlist in 1993, women’s groups—both conservative and liberal—raised concerns. As we discuss in our book “Shortlisted,” some feminists criticized Ginsburg’s position on equality as one that ignored the historic oppression of women. She advocated that men and women should be treated equally under the law, rather than receive special treatment based on their sex. Additionally, abortion opponents and champions alike expressed trepidation about her appointment.

That voices from the left and right contested her confirmation turned out to be a good thing, bringing consensus among senators who voted overwhelming in her favor, a vote of 96-3. Media reports described her as a “moderate” who deserved the “easy approval” based upon her qualifications as a civil rights lawyer and federal court judge.

Ginsburg was the last SCOTUS nominee to receive nearly unanimous support. (The vote for Justice Stephen Breyer, who followed her, was 87-9 and since that time opposition for every nominee has been in double-digits, most recently with the one of the closest votes ever confirming Justice Brett Kavanaugh 50-48). Many Senate Democrats already have pledged to vote “no” on Trump’s nominee to fill Ginsburg’s seat because they believe the nomination should be delayed until after presidential election results are in.

That Ginsburg had such a favorable vote from the Senate reflects the reality that she was not, at the time, thought of as the feminist icon she would later become. Rather, she was viewed by many as the embodiment of a Clinton moderate – a center-left thinker who might bring that sensibility to the bench.

In 1993, one could hardly anticipate the ferocious advocate – and dissenter – Justice Ginsburg would be during her tenure. As America mourns her momentous loss and prepares to face a confirmation process for her replacement where both gender and ideology promise to be primary issues, it’s worth pausing to remember the sweep of history that brought “moderate” Judge Ginsburg to the nation’s highest court.

Ginsburg’s nomination to fill the seat vacated by retiring Justice Byron White occurred on the heels of the debacle of the Clarence Thomas confirmation. Anita Hill’s highly credible accusations of his sexual harassment (which Thomas denied) and the humiliating spectacle of how some senators treated Hill during the 1991 hearings ushered in 1992’s “Year of the Woman,” during which women swept into political offices in unprecedented numbers. Ginsburg rode that wave, but she was not Clinton’s first choice. His top pick was reportedly New York’s governor Mario Cuomo, whom Clinton had courted for months. When Cuomo let the opportunity pass, Clinton apparently mused about other possible candidates, including his own wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton.

At the same time, Judge Ginsburg’s husband and champion Marty Ginsburg was working behind the scenes to secure support for his wife’s candidacy from across the country, seeking letters authored by lawyers, legal scholars and political organizations.

Soliciting that support was not so challenging. Ginsburg’s impeccable background made her particularly well-suited for the Court. She attended Cornell University for her undergraduate degree and started law school at Harvard, where she was one of only a handful of women in a class of more than 500. She transferred to Columbia Law School, where she tied for first place in her graduating class and later served as a tenured professor after beginning her academic career at Rutgers School of Law. Ginsburg argued six cases—and won five—in front of the Supreme Court before she became a judge, all of which dealt with gender discrimination in some way. She went to work for the American Civil Liberties Union in 1973 and was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in 1980.

Although President Carter made no nominations to the Supreme Court during his term, he implemented a plan for diversifying the federal bench more successfully than any other president before him. Carter understood that judicial appointments are among the most powerful roles of a president as most of the judges remain in office long beyond a presidential term. In February 1977, Carter issued an executive order establishing the United States Circuit Judge Nominating Commission with the explicit goal to increase diversity.

Thirteen panels were created representing regions across the country, with a specific mandate that each include men, women and minorities. Charged with nominating appropriate candidates for the federal judiciary, the panels were required to identify steps taken to give public notice to minorities and women, including the names of organizations and groups receiving notice, as well as lists of all women and minorities who responded as well as who had been considered.

The Carter administration also required the panels to ask targeted questions of judicial candidates like, “How have you worked to further civil rights, women’s rights, or the rights of other disadvantaged groups on a national, state or local level?” “How many women attorneys and minority attorneys does your office or law firm include?” “How many women partners?” “Minority partners?” “What do you think the most crucial legal problems of women and minorities will be over the next few years? How should these problems be remedied?” Under Carter’s leadership, a personal commitment to diversity became a qualification for a federal court appointment.

Carter’s effort led to five times more the number of women in federal judgeships than the presidents before him combined by the end of his presidency. As Carter said in a speech to the National Association of Women Judges in 1980, “When I became President, only 10 women had ever been appointed to the federal bench in more than 200 years. I’ve appointed 40 more.” Let that sink in. Among those women? The Notorious RBG, whom he appointed to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in 1980. But for Carter’s efforts to diversify the federal judiciary, she might never have gained this judicial experience that made her candidacy so attractive to President Clinton when he selected her for the Supreme Court.

Whether Trump succeeds in filling the vacancy left by Ginsburg’s death in the coming weeks or it is delayed until after the presidential election, the judicial selection process would benefit from reforms reflecting the priorities of Carter’s judicial commission. It is appalling that less than 4% of the justices serving on our Supreme Court have been women and that women still do not comprise an equal number of judges sitting on lower federal courts.

When President Barack Obama greeted RBG at Justice Elena Kagan’s swearing-in, he asked her: “Are you happy that I brought you two women?” Ginsburg replied, “Yes, but I’ll be happier when you bring me five more.” We will be happier too, seeing more women selected for the Supreme Court and positions of power across all professions.