Moments after Alyssa McLemore called 911 and asked for help on April 9, 2009, the line went dead.

Authorities were unable to trace the exact call location and never reached her. Police in the Seattle suburb of Kent showed up at the 21-year-old’s door to see if she was there. She wasn’t.

Days later McLemore missed her own mother’s funeral, and she’s missed every family gathering since. McLemore, who would be 31 today, is one of the thousands of Native American women who go missing or are victims of violence every year, both on reservations and in cities.

It is a problem so pervasive that, in some places, Native American women are more than 10 times more likely than the rest of the population to be murdered, according to a Department of Justice-funded study by researchers at the University of Delaware and the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

That stunning statistic is more than a decade old, but the issue of missing and murdered women is much older than that. One estimate from the National Crime Information Center shows 5,712 reports of missing Native American women in 2016 alone – yet reliable, comprehensive data on the problem is still almost impossible to come by.

Alaskan Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski is a member of a bipartisan group of lawmakers pushing two bills in the senate that aim to first understand the scope of the problem, and then figure out how to fix it.

‘They wrote her off’

Alyssa McLemore had her share of challenges in life. At 21, she was already raising a 3-year-old child and caring for her dying mother. A year before she went missing she was picked up on prostitution charges.

“I just kind of feel like they wrote her off as a prostitute and they probably [thought] that, you know, she didn’t have family,” said Tina Russell, McLemore’s aunt.

Kent Police deny that McLemore’s case was initially dismissed. It is still an open investigation, but there is precious little information to go on.

Some 20 formal interviews were conducted after McLemore went missing. One witness told police she was seen getting into a 1990s model green truck, but police aren’t even certain the sighting was the same day she went missing.

Police have the 911 call – but it’s only about 10 seconds long. In it, you can hear distress in McLemore’s voice, according to Detective Brendan Wales, who has had the case on his desk since 2011. He has a recording of the call in his car, and he plays it back sometimes in case one day he might notice something different, or significant.

“You never know what you could get from hearing something again and again and again,” he said.

Wales said the 911 call was only able to be traced to the cell tower it pinged off – meaning McLemore could have been anywhere within a 2-mile radius of the tower. He has resubmitted the audio to the FBI to be reanalyzed and is also sending it to two outside analysts to see if any other voices can be heard. McLemore’s family has not heard the tape, and Wales said they won’t be able to while the case is open.

Nonetheless, Russell is doing everything she can to keep warm a trail that has long gone cold – organizing volunteers in the summer to search and hand out “missing” flyers. They even once found bones at the bottom of a steep ravine based on an unsolicited tip from a local psychic. Police testing showed they belonged to a deer.

“We’re just stuck with those two tips. That’s all we found out in 10 years,” said Russell.

On Sunday, about 50 people – mostly friends and family – gathered in a park in Kent to mark 10 years since McLemore went missing. It’s been a long time, but Russell is optimistic that more public attention can lead to a break in the case.

‘What are we missing here?’

Russell beamed with excitement as she told the crowd about a secret announcement she’s been waiting to tell them. McLemore’s photo will soon be plastered on the side of large truck – in hopes that it will jog someone’s memory. A recent article in The Seattle Times undoubtedly helped, too. It’s only the second time her name has appeared in the newspaper. A brief article appeared eight days after she disappeared in 2009.

Until last year, Russell was naive to the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women. Offered support by an advocacy group dedicated to the cause, she was initially uncomfortable with the idea of helping only women of one particular race. But, when she heard how acute the problem was, specifically among Native Americans, she accepted.

“When you look at most of the people coming up missing that are white, most of the time there’s so much immediate response and news coverage,” Russell said.

“What are we missing here? What is happening with our native women that they are being victimized to the extent and the level that they are?” Those are the questions Murkowski says she is trying to sort out.

Some reservations have no police

The “Not Invisible Act,” introduced last week, aims to get victims, tribal leaders, federal agencies and law enforcement to bring forward recommendations on what might work.

That bill follows “Savanna’s Act,” which was reintroduced in January. It is named for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a pregnant woman killed in Fargo, North Dakota, in 2017. It aims to improve the collection of data on missing and murdered Native American women.

Murkowski said many women disappear from remote reservations – some that lack even a single police officer. Other times, cases get lost in a confusing web of jurisdictional conflicts between tribal, local and state police. She also worries that some victims are simply discounted because of their race or involvement in prostitution.

“Which makes no sense whatsoever and it doesn’t mean that we should give up or that the system should not work to investigate, to find out where that woman has gone,” she said.

“The resources are spread so thin, it allows people to fall through the cracks,” said Billy J. Stratton, an expert in Native American studies at the University of Denver.

Stratton thinks there ought to be more police resources on reservations, but said the broader problem goes much deeper than that.

“When you’re talking about a group of people who is among the lowest socioeconomic class in the US, they’re more susceptible to violence than others,” he said.

“Poverty is the main driver; dispossession, lack of empowerment, isolation, and those other social problems I think flow from that.”

‘It hardly gets talked about’

Roxanne White is a Native American activist and a victim of sex-trafficking herself. Years ago, she had never even heard the term “missing and murdered indigenous women.”

“But, did I know that violence against myself and other native women has been an issue? Yes. All my life,” she said.

In Canada, the problem is so acute that it sparked a national inquiry due to wrap up this month, but in the United States, “It hardly gets talked about,” said White. Washington state is one of the few exceptions. Lawmakers there have passed a new law requiring the state police to gather data on the number of missing and murdered Native women.

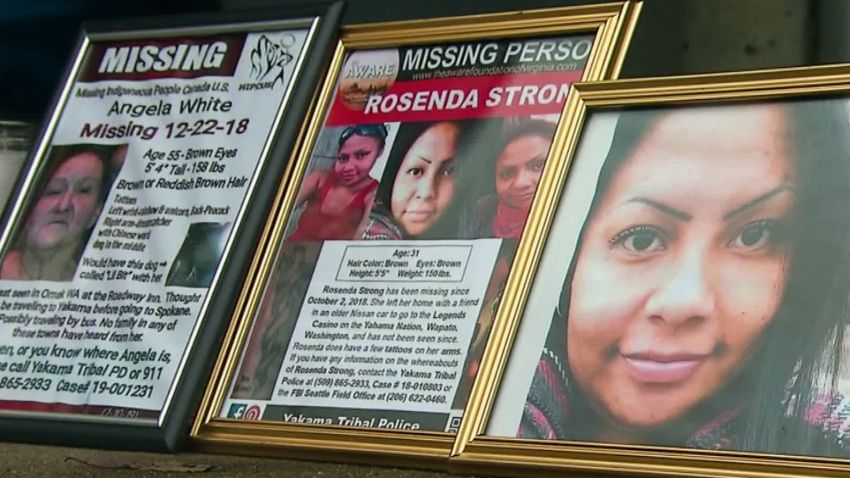

White’s own cousin is among those who will be counted. Rosenda Strong went missing from the Yakama Reservation in October.

Strong was last seen leaving the Legends Casino in Toppenish, Washington, on October 2 last year.

Strong’s sister Cissy Strong-Reyes said tribal police were initially dismissive of the disappearance because her sister used drugs.

“When I told the cops, they said, ‘well, she’s just probably partying, getting, you know, doing drugs,’” she recalled.

She’s optimistic about the FBI’s involvement after an agent first approached her in mid-October to tell her they were looking into her sister’s case. The FBI said it’s investigating at the request of the Yakama Tribal Police. Strong-Reyes is highly critical of the system of law enforcement on the reserve. She said tribal police are understaffed and largely unaccountable. State police, or the local non-native police typically have no jurisdiction to investigate on Yakama Nation land, unless the investigation involves a non-native person.

“People are getting killed, and it’s swept under the rug,” she said. “To me out there, it’s like the wild wild west.”

The Yakama Nation Tribal Police declined to comment, referring calls to the Tribal Council and the FBI. The Tribal Council has so far not commented to CNN.