On 9 March 2015, a student hurled faeces at a statue of British colonialist Cecil Rhodes. This act led to the statue’s removal. It also inspired the most significant period of student protest in post-apartheid South Africa’s history.

Student protesters called for the decolonisation of universities and public life. They spurred similar actions by student activists in the Global North. Students in other African countries like Ghana and Uganda also got involved. But the debate about what the decolonisation agenda means and who has the authority to lead it is still wide open – and often acrimonious.

The lessons from older, non-South African experiences of student protests in post-colonial African politics are often missing from those debates.

After independence, generations of university students in countries like Uganda, Kenya, Angola and Zimbabwe mobilised for change. They wanted politics and education to be decolonised, transformed and Africanised. These cases, and others, are explored in a special edition of the journal Africa.

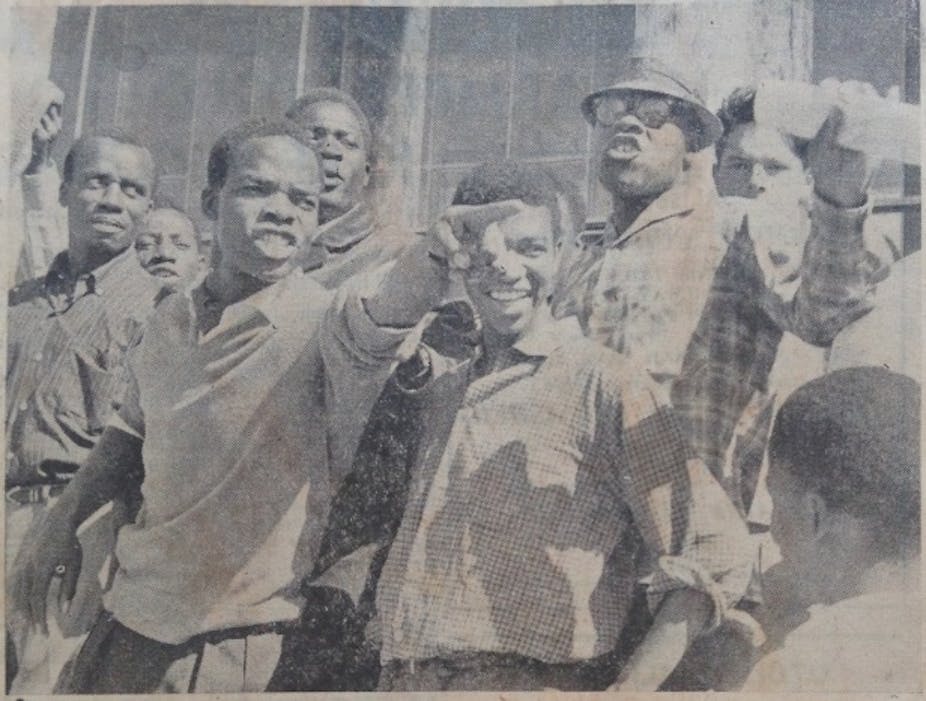

Today’s student activism and that which came before it share two common traits. One is student protestors’ belief in their own political agency. The other is the fear state authorities have that these groups may, in the words of Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani, act as a “catalytic force”. They have the power to spur other groups into action.

By looking back, scholars can understand the potential that such activism has for emancipating people from the legacies of colonialism. It’s also a useful way to identify the limits that student decolonisation projects can hold for both broader politics and society, as well as for the activists themselves.

Looking back

In our introduction to the journal, we point out that African students in the 1960s and 1970s believed themselves to be emergent political elites and intellectuals.

They questioned political leaders’ assumed role as the agents of decolonisation. They agitated for radical alternative projects of political change. These projects commonly incorporated socialist or pan-African ideological frameworks.

African universities were key actors in developing post-colonial and decolonised societies. They trained an entire new class of doctors, economists, lawyers, and other professionals.

This was happening in countries with low levels of formal schooling. And so, university students’ education was seen to give them the knowledge and skills to both understand and challenge state authority in a way that few other social groups could. These challenges led to frequent clashes between university students and the states that funded their education.

Historical protests

There was no single decolonisation project during this era. Students’ challenges to state authority looked very different in different countries. The fatal contests between radical Islamist and secular Leftist students at the University of Khartoum in Sudan in the late 1960s offer one example.

These two factions debated and violently fought over whether a decolonised Sudan should be secular and socialist, or bound by Islamic customs and values. Women’s public performances of their femininity became a lightning rod for these tensions. This boiled over into tragedy after the Adjako women’s dance was controversially performed in front of a campus crowd of men and women. The Islamic movement denounced this. Riots ensued, and a student was trampled to death.

Another example was how the 1961 assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba influenced students in the Democratic Republic of Congo. His death pushed young educated Congolese to revisit the meaning of decolonisation. They turned ideologically to the Left. This shaped the ideas and practices of a generation who challenged President Mobutu Sese Seko’s authoritarian rule.

New understandings

Scholars of African student activism have typically devoted more time to analysing earlier historical periods. These include the early anti-colonial activism of nationalist leaders such as Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta in London, or Senegal’s Leopold Senghor in Paris.

By focusing on the 1960s and 1970s, the research that appears in the special edition opens up new ways of thinking about the significance of African student activism. Some students took their political ideas and behaviour into subsequent careers as opposition political leaders in Kenya, Niger and Uganda. In Zimbabwe and Angola, on the other hand, student activism opened the way into high-status careers as state leaders. These former protesters’ uncomfortable association with authoritarian governance forced them to defend the meaning of their past activism.

The articles show how decolonisation in this period shaped a generation of university students’ aspirations to challenge post-colonial forms of governance.