Sure, Democrats might not actually have the votes to pass a $15 minimum wage as part of their big coronavirus relief package—but they’re giving it a shot anyway. And this week, the effort is about to face one of its most important legislative tests, as lawmakers meet with the Senate’s parliamentarian to try to convince her that they should be allowed to tack the hike onto their bill.

Whether they succeed will largely boil down to how the parliamentarian interprets a single word contained in a law governing congressional procedure: incidental. Beyond the fate of the minimum wage, her reading of this all-important adjective could also have serious implications for major Democratic priorities such as immigration reform.

Does this seem preposterous? It should. Vast swaths of the Biden administration’s agenda currently hang on the subjective linguistic judgment of an unelected congressional functionary, whose job is to advise senators on matters of procedure. But that’s the reality we’re currently stuck in, since moderate Democrats have refused to junk the Senate filibuster, preferring instead to force their party through joint-popping procedural contortions in order to pass laws.

To be specific, the party is attempting to enact its COVID rescue through budget reconciliation, the baroque maneuver that bars filibusters on certain tax and spending bills, allowing them to pass with a bare majority. This process is governed by a statute known as the Byrd rule, named for the late Sen. Robert Byrd. Crucially, it states that in order to pass via reconciliation, each provision of a bill must have an impact on the federal government’s finances that is not “merely incidental“ to its nonbudgetary components.

What does incidental mean? That’s the $15 question at the moment. Nobody has ever formally defined the term. There’s no official rubric for what counts and what doesn’t, no multipart test we can all check at a glance. Instead, the Senate has traditionally left it up to the parliamentarian to decide what passes muster, based on a loose series of precedents.

Still, the conventional rule of thumb about reconciliation is that Congress can only use it to pass laws that are primarily concerned with how the government spends money or collects it, rather than regulatory matters. Just because a piece of a bill could affect the federal budget doesn’t make it eligible. The current parliamentarian severely complicated Republican attempts to repeal Obamacare during the Trump administration by ruling that pieces of their proposals were Byrd rule violations, even though they had some nominal connection to spending. (She said that defunding Planned Parenthood was a no-go, for instance.) Most famously, she concluded that lawmakers could not eliminate the law’s individual mandate requiring Americans to buy health insurance or pay a fine, despite the fact that the Congressional Budget Office believed doing so would have had a large impact on health expenditures. This led Republicans to rewrite their bill so it simply reduced the fine to zero, while technically leaving the mandate in place on paper.

For those reasons, many have been skeptical that Democrats could pass a minimum wage increase through reconciliation. Increasing pay for workers would undoubtedly affect the federal budget—by decreasing spending on safety-net programs like food assistance, for instance. But in the eyes of many policymakers, those changes seem like incidental effects of a labor regulation that would have much larger consequences for the private sector than the government.

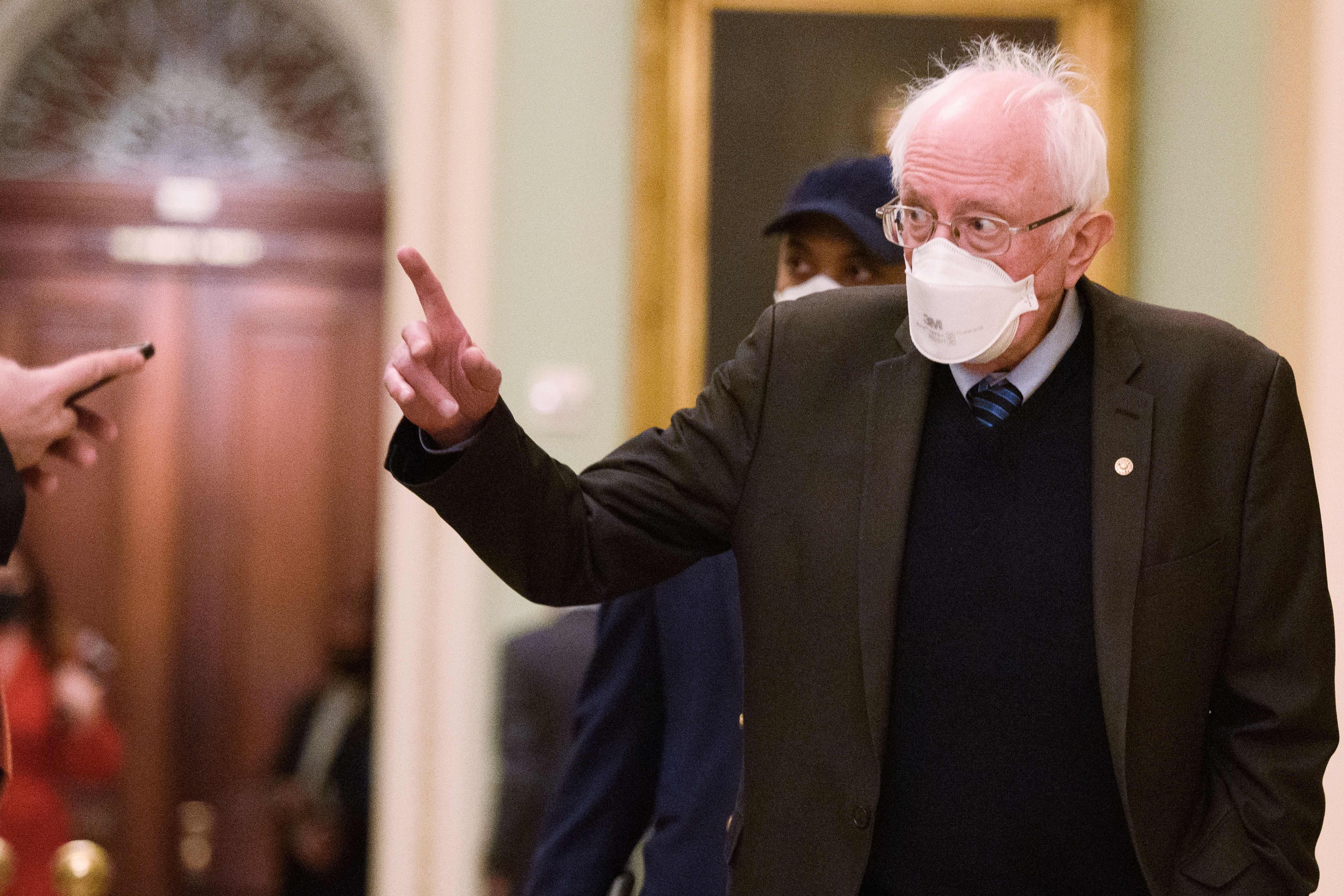

Nevertheless, progressives, led by Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders, are giving it a shot. They will get to make their case to the parliamentarian directly on Wednesday during a ritual affectionately known as the Byrd bath. Members of both parties will gather to present their best arguments for why pieces of the COVID relief package should or shouldn’t be considered eligible for reconciliation; the minimum wage will almost certainly be the hottest topic of discussion. Democrats plan to make two main points. First, hiking the pay floor would have a budget impact—the Congressional Budget Office has concluded that it would increase the deficit by $54 billion over a decade (rising tax revenues and falling safety-net spending would be canceled out by things like higher health care costs as labor becomes more expensive for providers). Second, they claim that the parliamentarian has already created a precedent for letting Congress use reconciliation to pass economic regulations with small budget impacts, such as when she allowed Republicans to open up Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for oil development in their 2017 tax bill. Yes, it gave the federal government the opportunity to auction oil leases, but the point was mostly to end the region’s drilling ban.

The outcome of this argument won’t just affect whether Democrats are able to pass a minimum wage increase. If the the parliamentarian adopts a broad reading of the Byrd rule, it could potentially open the door for other major pieces of legislation with significant budget consequences that aren’t traditionally thought of as tax and spending bills. One of the most consequential might be immigration reform, which the Congressional Budget Office has previously suggested would decrease the deficit by growing the country’s tax base. If the parliamentarian chooses a narrower reading, however, it could further limit the party’s realistic agenda going forward.

Technically, Democrats could choose to ignore the parliamentarian if she rules against them. Officially, she just offers advice. And under the rules of reconciliation, the presiding officer of the Senate (in this case, probably Vice President Kamala Harris) gets final say over what’s kosher and what isn’t. But in the past, Congress has almost always deferred to the parliamentarian’s judgment, and Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia has said he’d oppose any attempt to override her. “My only vote is to protect the Byrd Rule: hell or high water,” Manchin told CNN recently. “Everybody knows that. I’m fighting to defend the Byrd rule. The president knows that.”

The idea that the Byrd rule itself is in any way sacrosanct is more than a bit silly. It was only enacted during the mid-’80s to put a few guardrails on the reconciliation process, which itself was a historical accident, not unlike the modern filibuster. But in the end, what Manchin is really fighting against is the idea of pure majority rule, which he and a handful of other moderates have come to regard as anathema. The fact that it could stop Democrats from passing popular policies like a minimum wage hike? Maybe that’s secretly their goal. Or maybe it’s merely incidental.