Preface Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) is a digital form of currency notes issued by a central bank. While most central banks across the globe are exploring the issuance of CBDC, the key motivations for its issuance are specific to each country’s unique requirements. This Concept Note explains the objectives, choices, benefits and risks of issuing a CBDC in India, referred to as e₹ (digital Rupee). The e₹ will provide an additional option to the currently available forms of money. It is substantially not different from banknotes, but being digital it is likely to be easier, faster and cheaper. It also has all the transactional benefits of other forms of digital money. The purpose behind the issue of this Concept Note is to create awareness about CBDCs in general and the planned features of the digital Rupee, in particular. The Note also seeks to explain Reserve Bank’s approach towards introduction of the digital Rupee. Reserve Bank’s approach is governed by two basic considerations – to create a digital Rupee that is as close as possible to a paper currency and to manage the process of introducing digital Rupee in a seamless manner. The Concept Note also discusses key considerations such as technology and design choices, possible uses of digital rupee, issuance mechanisms etc. It examines the implications of introduction of CBDC on the banking system, monetary policy, financial stability, and analyses privacy issues. The Reserve Bank will soon commence limited pilot launches of e₹ for specific use cases. It is expected that this note would facilitate a deeper appreciation and understanding of digital Rupee and help members of public prepare for its use. |

List of Abbreviations | AML/CFT | Anti-Money Laundering/ Combating the Financing of Terrorism | | BBPOUs | Bharat Bill Payment Operating Units | | BBPS | Bharat Bill Payment System | | BIS | Bank for International Settlements | | CBDC | Central Bank Digital Currency | | CBDC-R | CBDC Retail | | CBDC-W | CBDC Wholesale | | CDD | Customer Due Diligence | | CPMI-MC | Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the Markets Committee | | CTS | Cheque Truncation System | | DEA | Department of Economic Affairs | | DLT | Distributed Ledger technology | | DPI | Digital Payment Index | | ECB | European Central Bank | | ECS | Electronic Clearing Service | | FATF | Financial Action Task Force | | FPS | Fast Payment Systems | | GDP | Gross Domestic Product | | IMF | International Monetary Fund | | IMPS | Immediate Payment Service | | IOSCO | International Organisation of Securities Commissions | | KYC | Know Your Customer | | NACH | National Automated Clearing House | | NDTL | Net Demand and Time Liabilities | | NEFT | National Electronic Funds Transfer | | NETC | National Electronic Toll Collection | | RBI | Reserve Bank of India | | RTGS | Real Time Gross Settlement | | TSPs | Token Service Providers | | UPI | Unified Payments Interface |

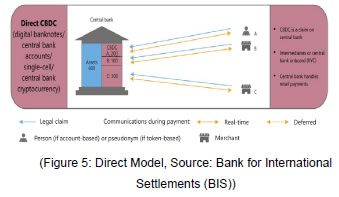

Summary Management of currency is one of the core central banking functions of the Reserve Bank for which it derives the necessary statutory powers from Section 22 of the RBI Act, 1934. Along with the Government of India, the Reserve Bank is responsible for the design, production and overall management of the nation’s currency, with the goal of ensuring an adequate supply of clean and genuine notes in the economy. The history of money is fascinating and goes back thousands of years. From the early days of bartering to the first metal coins and eventually the first paper money, it has always had an important impact on the way we function as a society. The innovations in money and finance go hand in hand with the shifts in monetary history. In its evolution till date, currency has taken several different forms. It has traversed its path from barter, to valuable metal coins made up of bronze and copper which later evolved to be made up of silver and gold. Use of coins was a huge milestone in the history of money because they were one of the first currencies that allowed people to pay by count (number of coins) rather than weight. Somewhere along the way, people improvised by using claims on goods and a bill of exchange. Money either has intrinsic value or represents title to commodities that have intrinsic value or title to other debt instruments. In modern economies, currency is a form of money that is issued exclusively by the sovereign (or a central bank as its representative) and is legal tender. Paper currency is such a representative money, and it is essentially a debt instrument. It is a liability of the issuing central bank (and sovereign) and an asset of the holding public. Irrespective of the form of money, in any economy, money performs three primary functions - medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. Money as a medium of exchange may be used for any transactions wherein goods or services are purchased or sold. Money as a unit of account can be used to value goods or services and express it in monetary terms. Money can also be stored or conserved for future purposes. India has made impressive progress towards innovation in digital payments. India has enacted a separate law for Payment and Settlement Systems which has enabled an orderly development of the payment eco-system in the country. The present state-of-the-art payment systems that are affordable, accessible, convenient, efficient, safe, secure and available 24x7x365 days a year are a matter of pride for the nation. This striking shift in payment preference has been due to the creation of robust round the clock electronic payment systems such as Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) and National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) that has facilitated seamless real time or near real time fund transfers. In addition, the launch of Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) and Unified Payments Interface (UPI) for instant payment settlement, the introduction of mobile based payment systems such as Bharat Bill Payment System (BBPS), and National Electronic Toll Collection (NETC) to facilitate electronic toll payments have been the defining moments that has transformed the payments ecosystem of the country and attracted international recognition. The convenience of these payment systems ensured rapid acceptance as they provided consumers an alternative to the use of cash and paper for making payments. The facilitation of non-bank FinTech firms in the payment ecosystem as PPI issuers, Bharat Bill Payment Operating Units (BBPOUs) and third-party application providers in the UPI platform have furthered the adoption of digital payments in the country. Throughout this journey, the Reserve Bank has played the role of a catalyst towards achieving its public policy objective of developing and promoting a safe, secure, sound, efficient and interoperable payment system. With the developments in the economy and the evolution of the payments system, the form and functions of money has changed over time, and it will continue to influence the future course of currency. The concept of money has experienced evolution from Commodity to Metallic Currency to Paper Currency to Digital Currency. The changing features of money are defining new financial landscape of the economy. Further, with the advent of cutting-edge technologies, digitalization of money is the next milestone in the monetary history. Advancement in technology has made it possible for the development of new form of money viz. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). Recent innovations in technology-based payments solutions have led central banks around the globe to explore the potential benefits and risks of issuing a CBDC so as to maintain the continuum with the current trend in innovations. RBI has also been exploring the pros and cons of introduction of CBDCs for some time and is currently engaged in working towards a phased implementation strategy, going step by step through various stages of pilots followed by the final launch, and simultaneously examining use cases for the issuance of its own CBDC (Digital Rupee (e₹)), with minimal or no disruption to the financial system. Currently, we are at the forefront of a watershed movement in the evolution of currency that will decisively change the very nature of money and its functions. Reserve Bank broadly defines CBDC as the legal tender issued by a central bank in a digital form. It is akin to sovereign paper currency but takes a different form, exchangeable at par with the existing currency and shall be accepted as a medium of payment, legal tender and a safe store of value. CBDCs would appear as liability on a central bank’s balance sheet. Bank for International Settlement has laid down “foundational principles” and “core features” of a CBDC, to guide exploration and support public policy objectives, as per the need of existing mandate of Central Banks. The foundational principles emphasise that, authorities would first need to be confident that issuance would not compromise monetary or financial stability and that a CBDC could coexist with and complement existing forms of money, promoting innovation and efficiency. Key Motivations CBDC, being a sovereign currency, holds unique advantages of central bank money viz. trust, safety, liquidity, settlement finality and integrity. The key motivations for exploring the issuance of CBDC in India among others include reduction in operational costs involved in physical cash management, fostering financial inclusion, bringing resilience, efficiency, and innovation in payments system, adding efficiency to the settlement system, boosting innovation in cross-border payments space and providing public with uses that any private virtual currencies can provide, without the associated risks. The use of offline feature in CBDC would also be beneficial in remote locations and offer availability and resilience benefits when electrical power or mobile network is not available. Private virtual currencies sit at substantial odds to the historical concept of money. They are not commodities or claims on commodities as they have no intrinsic value. The rapid mushrooming of private cryptocurrencies in the last few years has attempted to challenge the fundamental notion of money as we know it. Claiming the benefits of de-centralisation, cryptocurrencies are being hailed as innovation that would usher in de-centralised finance and disrupt the traditional financial system. However, the inherent design of cryptocurrencies is more geared to bypass the established and regulated intermediation and control arrangements that play a crucial role of ensuring integrity and stability of monetary and financial eco-system. As the custodian of monetary policy framework and with the mandate to ensure financial stability in the country, the Reserve Bank of India has been consistent in highlighting various risks related to the cryptocurrencies. These digital assets undermine India’s financial and macroeconomic stability because of their negative consequences for the financial sector. Further, a wider proliferation of cryptocurrencies has the potential to diminish monetary authorities’ potential to determine and regulate monetary policy and the monetary system of the country which could pose serious challenge to the stability of the financial system of the country. In this context, it is the responsibility of central bank to provide its citizens with a risk free central bank digital money which will provide the users the same experience of dealing in currency in digital form, without any risks associated with private cryptocurrencies. Therefore, CBDCs will provide the public with benefits of virtual currencies while ensuring consumer protection by avoiding the damaging social and economic consequences of private virtual currencies. Design Choices As CBDCs are electronic form of sovereign currency, it should imbibe all the possible features of physical currency. The design of CBDC is dependent on the functions it is expected to perform, and the design determines its implications for payment systems, monetary policy as well as the structure and stability of the financial system. One of the main considerations is that the design features of CBDCs should be least disruptive. The key design choices to be considered for issuing CBDCs include (i) Type of CBDC to be issued (Wholesale CBDC and/or Retail CBDC), (ii) Models for issuance and management of CBDCs (Direct, Indirect or Hybrid model), (iii) Form of CBDC (Token-based or Account-based), (iv) Instrument Design (Remunerated or Non-remunerated) and (v) Degree of Anonymity. Type of CBDC to be issued CBDC can be classified into two broad types viz. general purpose or retail (CBDC-R) and wholesale (CBDC-W). Retail CBDC would be potentially available for use by all viz. private sector, non-financial consumers and businesses while wholesale CBDC is designed for restricted access to select financial institutions. While Wholesale CBDC is intended for the settlement of interbank transfers and related wholesale transactions, Retail CBDC is an electronic version of cash primarily meant for retail transactions. It is believed that Retail CBDC can provide access to safe money for payment and settlement as it is a direct liability of the Central Bank. Wholesale CBDC has the potential to transform the settlement systems for financial transactions and make them more efficient and secure. Going by the potential offered by each of them, there may be merit in introducing both CBDC-W and CBDC-R. Model for issuance and management of CBDC There are two models for issuance and management of CBDCs viz. Direct model (Single Tier model) and Indirect model (Two-Tier model). A Direct model would be the one where the central bank is responsible for managing all aspects of the CBDC system viz. issuance, account-keeping and transaction verification. In an Indirect model, central bank and other intermediaries (banks and any other service providers), each play their respective role. In this model central bank issues CBDC to consumers indirectly through intermediaries and any claim by consumers is managed by the intermediary as the central bank only handles wholesale payments to intermediaries. The Indirect model is akin to the current physical currency management system wherein banks manage activities like distribution of notes to public, account-keeping, adherence of requirement related to know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering and countering the terrorism of financing (AML/CFT) checks, transaction verification etc. Forms of CBDC CBDC can be structured as ‘token-based’ or ‘account-based’. A token-based CBDC is a bearer-instrument like banknotes, meaning whosoever holds the tokens at a given point in time would be presumed to own them. In contrast, an account-based system would require maintenance of record of balances and transactions of all holders of the CBDC and indicate the ownership of the monetary balances. Also, in a token-based CBDC, the person receiving a token will verify that his ownership of the token is genuine, whereas in an account-based CBDC, an intermediary verifies the identity of an account holder. Considering the features offered by both the forms of CBDCs, a token-based CBDC is viewed as a preferred mode for CBDC-R as it would be closer to physical cash, while account-based CBDC may be considered for CBDC-W. Technology choice CBDCs being digital in nature, technological consideration will always remain at its core. The infrastructure of CBDCs can be on a conventional centrally controlled database or on Distributed Ledger Technology. The two technologies differ in terms of efficiency and degree of protection from single point of failure. The technology considerations underlying the deployment of CBDC needs to be forward looking and must have strong cybersecurity, technical stability, resilience and sound technical governance standards. While crystallising the design choices in the initial stages, the technological considerations may be kept flexible and open-ended in order to incorporate the changing needs based on the evolution of the technological aspects of CBDCs. Instrument Design The payment of (positive) interest would likely enhance the attractiveness of CBDCs that also serves as a store of value. But, designing a CBDC that moves away from cash-like attributes to a “deposit-like” CBDC may have a potential for disintermediation in the financial system resulting from loss of deposits by banks, impeding their credit creation capacity in the economy. Also considering that physical cash does not carry any interest, it would be more logical to offer non-interest bearing CBDCs. Degree of Anonymity For CBDC to play the role as a medium of exchange, it needs to incorporate all the features that physical currency represents including anonymity, universality, and finality. Ensuring anonymity for a digital currency particularly represents a challenge, as all digital transactions would leave some trail. Clearly, the degree of anonymity would be a key design decision for any CBDC. In this regard, reasonable anonymity for small value transactions akin to anonymity associated with physical cash may be a desirable option for CBDC-R. While the intent of CBDC and the expected benefits are well understood, it is important that the issuance of CBDC needs to follow a calibrated and nuanced approach with adequate safeguards to address potential difficulties and risks in order to build a system which is inclusive, competitive and responsive to innovation and technological changes. CBDC, across the world, is mostly in conceptual, developmental, or at pilot stages. Therefore, in the absence of a precedence, extensive stakeholder consultation along with iterative technology design may be the requirement, to develop a solution that meets the requirements of all stakeholders. CBDC is aimed to complement, rather than replace, current forms of money and is envisaged to provide an additional payment avenue to users, not to replace the existing payment systems. Supported by state-of-the-art payment systems of India that are affordable, accessible, convenient, efficient, safe and secure, the Digital Rupee (e₹) system will further bolster India’s digital economy, make the monetary and payment systems more efficient and contribute to furthering financial inclusion.

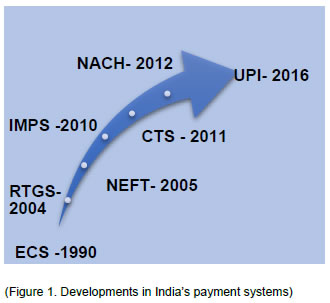

Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Maintaining monetary and financial stability and explicitly or implicitly promoting broad access to safe and efficient payments, have been among the main objectives of the RBI. Monetary stability is secured by virtue of the statutory responsibility of currency management conferred on the Reserve Bank in the Preamble of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, which mandates the Reserve Bank to regulate the issue of Bank notes and keeping of reserves. A core instrument by which central banks carry out their public policy objectives is by providing central bank money, which is the safest form of money to banks, businesses, and the public. 1.2 The history of money is fascinating and goes back thousands of years. From the early days of bartering to the first metal coins and eventually the first paper money, it has always had an important impact on the way we function as a society. The innovations in money and finance go hand in hand with the shifts in monetary history. In its evolution till date, currency has taken several different forms. It has traversed its path from barter to valuable metal coins made up of bronze and copper which later evolved to be made up of silver and gold. Somewhere along the way, people improvised and instead of actual goods for barter they started using claims on goods, a bill of exchange. 1.3 Money either has intrinsic value or represents title to commodities that have intrinsic value or title to other debt instruments. In modern economies, currency is a form of money that is issued exclusively by the sovereign (or a central bank as its representative) and is legal tender. Paper currency is such a representative money, and it is essentially a debt instrument. It is a liability of the issuing central bank (and sovereign) and an asset of the holding public. Central Bank Money acts as medium of payment, a unit of account and a store of value for a jurisdiction. 1.4 Payment systems are changing at an accelerating pace. Today, users expect faster, easier payments anywhere and at any time, mirroring the digitalisation and convenience of other aspects of life (Bech et al,2017). Systems that offer near instant person-to-person retail payments are becoming increasingly prevalent around the world. India has always been a country that has fostered innovation and development in the area of payment and settlement systems. The past decades have witnessed the blossoming of a myriad of payment systems, all for the convenience of the common man. Reserve Bank of India has taken several initiatives since the mid-eighties to bring in technology-based solutions to the banking system. The developments have been indicated in the chart given below1:  1.5 India has made impressive progress towards innovation in digital payments. India has enacted a separate law for Payment and Settlement Systems which has enabled an orderly development of the payment eco-system in the country. The present state-of-the-art payment systems that are affordable, accessible, convenient, efficient, safe, secure and available 24x7x365 days a year are a matter of pride for the nation. This striking shift in payment preference has been due to the creation of robust round the clock electronic payment systems such as RTGS and NEFT that has facilitated seamless real time or near real time fund transfers. In addition, the launch of IMPS and UPI for instant payment settlement, the introduction of mobile based payment systems such as BBPS, and National Electronic Toll Collection (NETC) to facilitate electronic toll payments have been the defining moments that has transformed the payments ecosystem of the country and attracted international recognition. The convenience of these payment systems ensured rapid acceptance as they provided consumers an alternative to the use of cash and paper for making payments. The facilitation of non-bank FinTech firms in the payment ecosystem as PPI issuers, BBPOUs and third-party application providers in the UPI platform have furthered the adoption of digital payments in the country. Throughout this journey, the Reserve Bank has played the role of a catalyst towards achieving its public policy objective of developing and promoting a safe, secure, sound, efficient and interoperable payment system. 1.6 Private virtual currencies sit at substantial odds to the historical concept of money. They are not commodities or claims on commodities as they have no intrinsic value. The rapid mushrooming of private cryptocurrencies in the last few years has attempted to challenge the fundamental notion of money as we know it. Claiming the benefits of de-centralisation, cryptocurrencies are being hailed as innovation that would usher in de-centralised finance and disrupt the traditional financial system. However, the inherent design of cryptocurrencies is more geared to bypass the established and regulated intermediation and control arrangements that play a crucial role of ensuring integrity and stability of monetary and financial eco-system. 1.7 As the custodian of monetary policy framework and with the mandate to ensure financial stability in the country, the Reserve Bank of India has been consistent in highlighting various risks related to the cryptocurrencies. These digital assets undermine India’s financial and macroeconomic stability because of their negative consequences for the financial sector. Further, a wider proliferation of cryptocurrencies has the potential to diminish monetary authorities’ potential to determine and regulate monetary policy and the monetary system of the country which could pose serious challenge to the stability of the financial system of the country. 1.8 In addition to the process of making payments, even the types of money being used for making payments are undergoing change. The Central Banks provide money to the public through physical cash and to banks and other financial entities through reserve and settlement accounts. Recent technological advances have ushered in a wave of new private-sector financial products and services, including digital wallets, mobile payment apps, and new digital assets. While cash is still the king (Bech et al (2018)), innovations are pushing Central Banks to think about how new central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) could complement or replace traditional money (Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the Markets Committee (CPMI-MC) (2018)). CBDC is a third form of base money, and central banks around the globe are exploring its feasibility, potential benefits, and the risks involved. As per the results of 2021 Bank for International Settlements (BIS) survey on CBDCs conducted on 81 central banks, 90% of central banks are engaged in some form of CBDC work and more than half are now developing them or running concrete experiments. 1.9 Recognising the global developments in the field of CBDC, the Reserve Bank had set up an Internal Working Group (WG) in October 2020 to undertake a study on appropriate design / implementation architecture for introducing CBDCs in India. The WG in their February 2021 report made the following major recommendations: -

Need for a robust legal framework to back the issuance of e₹ (Digital Rupee)2 as another form of currency. It was recommended to amend the RBI Act to cover e₹ in the definition of the term ‘bank note’ and also insert a new section in the RBI Act covering features pertaining to e₹ and necessary exemptions. -

The design of e₹ may be decided depending on the circumstances and the need of the country. It recommended that the design of e₹ should be compatible with the objectives of monetary and financial stability. -

The most widespread use and advantage of e₹ was expected to emerge from the token-based variant in the retail segment. Keeping this in mind, the WG recommended undertaking some pilot projects with phased implementation to serve as a learning experience. -

Implementation of a specific purpose e₹, one each in the wholesale and retail segments to begin with. The proposed models could be implemented with little or no disruption to the market and help unravel the benefits of CBDC. For Wholesale CBDC (CBDC-W), a phased implementation strategy for wholesale account-based CBDC3 model, in securities settlement (outright), was proposed. For Retail CBDC (CBDC-R), a token-based CBDC4 with tiered architecture model was proposed wherein the Reserve Bank shall only issue and redeem e₹ while the distribution and payment services will be delegated to the banks. -

As traceability, privacy and transaction costs vary for each CBDC type resulting in different cost implications for each stakeholder, the need to conduct more research on the technological aspects of CBDC implementation on a national scale was recommended. -

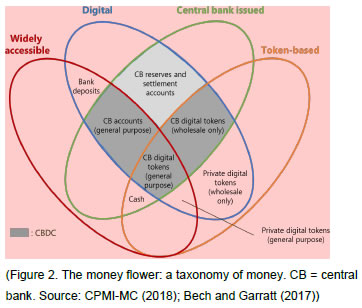

The WG was of the view that finalising a model for implementation of e₹ within a short duration may not be desirable and re-iterated that the initial models proposed be simple models that could be considered to commence work in this connection. The WG proposed to continue deliberations on CBDC over a longer period to refine and crystallise requirements for the implementation of other models of e₹ in future. 1.10 Earlier, in November 2017, a High Level Inter-ministerial committee was constituted under the chairmanship of the Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs (DEA), Ministry of Finance, Government of India (GoI) to examine the policy and legal framework for regulation of virtual / crypto currencies and recommend appropriate measures to address concerns arising from their use. The committee had recommended the introduction of CBDCs as a digital form of sovereign currency in India. 1.11 Across the globe, more than 60 central banks5 have expressed interest in CBDC with a few implementations already under pilot across both Retail6 and Wholesale7 categories and many others are researching, testing, and/or launching their own CBDC framework. As of July 2022, there are 105 countries8 in the process of exploring CBDC, a number that covers 95% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). 10 countries have launched a CBDC, the first of which was the Bahamian Sand Dollar in 2020 and the latest was Jamaica’s JAM-DEX. Currently, 17 other countries, including major economies like China and South Korea, are in the pilot stage and preparing for possible launches. China was the first large economy to pilot a CBDC in April 2020 and it aims for widespread domestic use of the e-CNY by 2023. Increasingly, CBDCs are being seen as a promising invention and as the next step in the evolutionary progression of sovereign currency. 1.12 Like other central banks, RBI has been exploring the pros and cons of introduction of CBDCs for some time. The introduction of CBDC in India is expected to offer a range of benefits, such as reduced dependency on cash, lesser overall currency management cost, and reduced settlement risk. It could provide general public and businesses with a convenient, electronic form of central bank money with safety and liquidity and provide entrepreneurs a platform to create new products and services. The introduction of CBDC, would possibly lead to a more robust, efficient, trusted, regulated and legal tender-based payments option (including cross-border payments). 1.13 However, CBDC could also pose certain risks that may have a bearing on important public policy issues, such as risk to financial stability, monetary policy, financial market structure and the cost and availability of credit. They need to be carefully evaluated against the potential benefits. 1.14 Government of India announced the launch of the Digital Rupee — a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) from FY 2022-23 onwards in the Union Budget placed in the Parliament on February 01, 2022. In the budget announcement it was stated that the introduction of CBDC will give a big boost to the digital economy. The broad objectives to be achieved by the introduction of CBDC using blockchain and other technologies as a ‘more efficient and cheaper currency management system’ were also laid down in the budget. 1.15 The Government of India vide gazette notification dated March 30, 2022 notified the necessary amendments in the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, which enables running the pilot and subsequent issuance of CBDC. 1.16 An internal high-level committee on CBDC under the chairmanship of Shri Ajay Kumar Choudhary, Executive Director, RBI was constituted in February 2022 by the Reserve Bank to brainstorm and undertake an extensive study on various aspects of CBDC and explore the motivation for the introduction of CBDC, its design features and its implications on policy issues, choice of technology platforms and accordingly suggest measures for its successful introduction. 1.17 Based on the deliberations in the Committee, the Reserve Bank hereby releases this Concept Note to present the background, motivation, choices of design features and other policy frameworks for e₹ system for the country. The aim is to build an open, inclusive, inter-operable and innovative CBDC system which will meet the aspirations of the modern digital economy of India. Chapter 2: CBDC – Conceptual Framework 2.1 What is CBDC? The report by the CPMI-MC published in 2018 defines CBDCs as new variants of central bank money different from physical cash or central bank reserve/settlement accounts. That is, a central bank liability, denominated in an existing unit of account, which serves both as a medium of exchange and a store of value. The four different properties of money are: (i) issuer (central bank or not); (ii) form (digital or physical); (iii) accessibility (wide or narrow); and (iv) technology (peer-to-peer tokens, or accounts) (Bech and Garratt (2017)). Based on these four properties, the CPMI-MC report provides a taxonomy of money (‘The Money Flower’), which delineates two broad types of CBDC: general purpose and wholesale – with the former type coming in two varieties (Figure 1).  Reserve Bank defines CBDC as the legal tender issued by a central bank in a digital form. It is the same as a sovereign currency and is exchangeable one-to-one at par (1:1) with the fiat currency9. While money in digital form is predominant in India—for example in bank accounts recorded as book entries on commercial bank ledgers—a CBDC would differ from existing digital money available to the public because a CBDC would be a liability of the Reserve Bank, and not of a commercial bank. 2.2 Features of CBDC The features of CBDC include: -

CBDC is sovereign currency issued by Central Banks in alignment with their monetary policy -

It appears as a liability on the central bank’s balance sheet -

Must be accepted as a medium of payment, legal tender, and a safe store of value by all citizens, enterprises, and government agencies. -

Freely convertible against commercial bank money and cash -

Fungible legal tender for which holders need not have a bank account -

Expected to lower the cost of issuance of money and transactions Chapter 3 - Motivations for issuance of CBDCs 3.1 Different jurisdictions have justified the adoption of CBDC for very diverse reasons. Some of them are enumerated below: -

Central Banks, faced with dwindling usage of paper currency, seek to popularise a more acceptable electronic form of currency (like Sweden); -

Jurisdictions with significant physical cash usage seeking to make issuance more efficient (like Denmark, Germany, Japan or even the US); -

Countries with geographical barriers restricting the physical movement of cash had motivation to go for CBDC (e.g. The Bahamas and the Caribbean with small and large numbers of islands spread out); -

Central Banks seek to meet the public’s need for digital currencies, manifested in the increasing use of private virtual currencies, and thereby avoid the more damaging consequences of such private currencies. 3.2 Further, CBDCs have some clear advantages over other digital payments systems, as it being a sovereign currency, ensures settlement finality and thus reduces settlement risk in the financial system. CBDCs could also potentially enable a more real-time, cost-effective seamless integration of cross border payment systems. India has made impressive progress in innovation in digital payments. The payment systems are available 24X7, 365 days a year to both retail and wholesale customers, they are largely real-time, the cost of transaction is perhaps the lowest in the world, users have a wide array of options for doing transactions and digital payments have grown at an impressive CAGR of 55% over the last five years. 3.3 Supported by the state-of-the-art payment systems of India that are affordable, accessible, convenient, efficient, safe and secure, the e₹ system will bolster India’s digital economy, enhance financial inclusion, and make the monetary and payment systems more efficient. There are a large and diverse number of motivations for India to consider CBDC. Some of the important motivations for India to consider issuing CBDC are given below. 3.3.1 Reduction in cost associated with physical cash management Cost of cash management in India has continued to be significant. The total expenditure incurred on security printing during April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022 was ₹4,984.80 crore as against ₹4,012.10 crore in the previous year (July 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021)10. This cost, which does not include the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) cost of printing money, is predominantly borne by four stakeholders –general public, businesses, banks, and the Central Bank. CBDC affects the overall value of the money issuing function to the extent that it reduces operational costs e.g. costs related to printing, storage, transportation and replacement of banknotes, and costs associated with delay in reconciliation and settlement. Though, at the outset, establishing a CBDC creation/issuance may entail significant fixed infrastructure costs but subsequent marginal operating costs shall be very low. Cost-effectiveness of cash management using CBDC vis-à-vis physical currency provides an additional motivation for introduction of CBDC, which may be also perceived to be environment friendly. Complementing the higher cash requirement of the country, CBDC will lead to lowering of cost as it would obviate the need of many processes associated with distribution of physical currency across the country. Further, given the geographical spread and pockets where making physical cash available is a challenge, CBDC is expected to facilitate seamless transactions. 3.3.2 To further the cause of digitisation to achieve a less cash economy. India has a unique case where the cash in the economy has shot up despite rapid digitisation in the payments space. The growing use of electronic medium of payment has not yet resulted in a reduction in the demand for cash. The percentage increase in value of banknotes during 2020-21 and 2021-22 was 16.8 per cent and 9.9 per cent respectively and the percentage increase in volume of banknotes during 2020-21 and 2021-22 was 7.2 per cent and 5.0 per cent respectively. (Source: RBI Annual Report for the year 2021-22) The year (2021-22) witnessed a higher than average increase in banknotes in circulation primarily due to precautionary holding of cash by the public induced by the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Further, a pilot survey conducted by the Reserve Bank on retail payment habits of individuals in six cities between December 2018 and January 2019, indicated that cash remains the most preferred mode of payment and for receiving money for regular expenses; it was followed by digital mode. For small value transactions (with amount up to ₹500) cash is used predominantly. CBDC can be a preferred mode of holding central bank money rather than cash in any uncertain situation like the one of pandemic COVID-19. Further, the preference for cash transactions for regular expenses and small payments for its anonymity, may be redirected to acceptance of CBDC, if reasonable anonymity is assured. This shall further the digitisation process in the country. The Reserve Bank Digital Payment index (RBI-DPI) demonstrates significant growth in adoption and deepening of digital payments across the country since its inception. | Period | RBI - DPI Index | | March 2018 (Base) | 100 | | March 2019 | 153.47 | | September 2019 | 173.49 | | March 2020 | 207.84 | | September 2020 | 217.74 | | March 2021 | 270.59 | | September 2021 | 304.06 | | March 2022 | 349.30 | | (Figure 4: RBI-DPI, Source: RBI) | This increase indicates that the digital payments are further deepening and expanding in the country and is an indication that, Indian citizens have an appetite for digital payments. Therefore, the digital currency issued by the central bank shall provide yet another option for furthering the cause of digital payment, apart from the range of other digital payment instruments available, given its ease of usage coupled with sovereign guarantee. 3.3.3 Supporting competition, efficiency and innovation in payments The digital revolution is taking the world by storm and no other area has witnessed such metamorphosis as payment and settlement systems, resulting in an array of digital options for the common man. Consumers now have a range of options to choose from when selecting a payment method to complete a transaction. They make this selection based on the value they attribute to a payment method in a certain situation as each payment mode has its own use and purpose. The shift from cash to electronic payments increases the reliance on electronic payment systems, which has implications for the diversity and resilience of the payments landscape. CBDC could further enhance resilience in payments and provide core payment services outside of the commercial banking system. It can provide a new way to make payments and also diversify the range of payment options, particularly for e-commerce (where cash cannot be used, except for the Cash on Delivery (COD) option). The CBDC based payment system is not expected to substitute other modes of existing payment options rather it will supplement by providing another payment avenue to the larger public. As has been the experience with many payment products, once CBDC is introduced, innovations around the product would only expand the choices available and healthy competition will help bringing about both cost and time efficiencies. Most payments in a modern economy are made with private money maintained by commercial banks, which are in the form of demand deposits and therefore liabilities of these banks. A key feature of bank deposits is that commercial banks guarantee convertibility on demand to central bank money at a fixed price, namely, at par, thereby maintaining the value of their money. Nevertheless, in a fractional reserve system, a commercial bank—even if solvent— may face a challenge to meet with any sudden spurt in demand to convert substantial amount of bank deposits to central bank money. A significant difference between the central bank money and commercial bank money is that central bank can meet its obligations using its own nonredeemable money, while the latter entails counterparty risk. Central Bank money is the only monetary asset in a domestic economy without credit and liquidity risk. Therefore, it is preferred asset to settle payments in financial market infrastructures (see CPMI-IOSCO Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (2012)). Therefore, an e₹ would offer the public broad access to digital money free from credit risk and liquidity risk. As such, it could provide a safe foundation for private-sector innovations to meet current and future needs and demands for payment services. It shall also help in levelling the playing field in payment innovation for firms of all sizes. For some smaller firms, the costs and risks of issuing a safe and robust form of private tender may be prohibitive. A CBDC could overcome this barrier and allow private-sector innovators to focus on new access services, distribution methods, and related service offerings. Finally, a CBDC might generate new capabilities to meet the evolving speed and efficiency requirements of the digital economy. Further, payments using CBDCs are final and thus reduce settlement risk in the financial system. CBDC will eliminate the need for interbank settlement by giving choices to market participants to choose among the various settlement options such as settlement in Central Bank / commercial bank accounts with / without using clearing corporations; or settlement on a bilateral basis without use of central counterparty by directly using CBDC accounts. It can be compared to a cash-based transaction, where instead of banknotes, CBDC is handed over leading to instant settlement. This is expected to bring in further efficiency in the payment system. 3.3.4 To explore the use of CBDC for improvement in cross-border transactions The present state-of-the-art payment systems of India are affordable, accessible, convenient, efficient, safe and secure and are a matter of pride for the nation. However, ‘Cross Border Payments’ is an area especially ripe for change and could benefit from new technologies. As per the World Bank, India is the world’s largest recipient of remittances as it received $87 billion in 2021 with the United States being the biggest source, accounting for over 20 per cent of these funds. The cost of sending remittances to India, therefore, assumes critical relevance, especially in view of the large Indian diaspora spread across the world and from the point of view of the potential (mis)use of informal / illegal channels. The G20 has also made enhancing cross-border payments a priority and endorsed a comprehensive programme to address the key challenges to cross border payment, namely high costs, low speed, limited access and insufficient transparency and frictions that contributed to these challenges. Faster, cheaper, more transparent, and more inclusive cross-border payment services would deliver widespread benefits for citizens and economies worldwide, supporting economic growth, international trade, global development and financial inclusion. BIS has published the results from a survey of Central Banks in June, 202111, which notes that CBDCs could ease current frictions in cross-border payments – and particularly so if central banks factor an international dimension into CBDC design from the outset. As noted by BIS, the potential benefits will be difficult to achieve unless central banks incorporate cross-border considerations in their CBDC design from the start and coordinate internationally. Many central banks are currently investigating risks, benefits and various designs of CBDC, mainly with a strong focus on domestic needs. Implications of CBDCs, even if only intended for domestic use, are expected to go beyond borders, making it crucial to coordinate work and find common ground among CBDCs of various jurisdictions. If coordinated successfully, the ‘clean slate’ presented by CBDCs may be leveraged to enhance cross-border payments. According to BIS survey among central banks in late 2020, cross-border payments efficiency is an important motivation for CBDC issuance, especially with regards to wholesale CBDC projects. CBDCs can boost innovation in cross-border payments, making these transactions instantaneous and help overcome key challenges relating to time zone, exchange rate differences as well as legal and regulatory requirements across jurisdictions. Additionally, the interoperability of CBDCs presents means to mitigate cross-border and cross-currency risks and frictions while reinforcing the role of central bank money as an anchor for the payment system. Therefore, the potential use of CBDC in alleviating challenges in cross-border payment is one of the major motivations for exploring issuance of CBDC. 3.3.5 Support financial inclusion The annual FI-Index for India for March 2022 is 56.4 vis-à-vis 53.9 in March 2021. It demonstrates the fact that despite various measures undertaken by various stakeholders in strengthening financial inclusion in the country, further coordinated effort is required by the policy makers to achieve the desired goal. Some of the existing challenges to financial inclusion include limited physical infrastructure - especially in remote areas, poor connectivity, non-availability of customized products, socio-cultural barriers, lack of integration of credit with livelihood activities or other financial services across insurance, pension etc. With suitable design choices, CBDC may provide the public a safe sovereign digital money for meeting various transaction needs. It shall make financial services more accessible to the unbanked and underbanked population. The offline functionality as an option will allow CBDCs to be transacted without the internet and thus enable access in regions with poor or no internet connectivity. It shall also create digital footprints of the unbanked population in the financial system, which shall facilitate the easy availability of credit to them. Universal access attributes of a CBDC including offline functionality, provision of universal access devices and compatibility across multiple devices, shall prove to be a gamechanger by improving the overall CBDC system for reasons of resilience, reach and financial inclusion. 3.3.6 Safeguard the trust of the common man in the national currency vis-à-vis proliferation of crypto assets Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank (ECB), chair of the group of central bank governors responsible for the report titled ‘Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features’, while releasing the report stated that “… central banks have a duty to safeguard people's trust in our money. Central banks must complement their domestic efforts with close cooperation to guide the exploration of central bank digital currencies to identify reliable principles and encourage innovation.” The proliferation of crypto assets can pose significant risks related to Money Laundering & Financing of Terrorism. Further, the unabated use of crypto assets can be a threat to the monetary policy objectives as it may lead to creation of a parallel economy and will likely undermine the monetary policy transmission and stability of the domestic currency. It will also adversely affect the enforcement of foreign exchange regulations, especially, the circumvention of capital flow measures. Further, developing CBDC could provide the public a risk free virtual currency that will provide them legitimate benefits without the risks of dealing in private virtual currencies. It may, therefore, fulfil demand for secured digital currency besides protecting the public from the abnormal level of volatility which some of these virtual digital assets experience. Thus, safeguarding the trust of the common man in the Indian Rupee vis-à-vis proliferation of crypto asset is another important motivation for introducing CBDC. Chapter 4 Design Consideration for CBDC 4.1 In the October 2020 report12, the BIS, in collaboration with several leading central banks, outlined the core features and foundational principles of a CBDC. In formulating its foundational principles, BIS (2020) followed a risk-based approach. It highlighted the need to identify all potential risks associated with issuing a CBDC, particularly those that threaten financial stability or negatively impact financial market structures. BIS, thus outlined three important foundational principles for central banks to consider in issuing a CBDC: (i) It should not interfere with public policy objectives or prevent banks from performing their monetary stability mandate (a “do no harm” principle). (ii) It should be used alongside and complement existing forms of money (the coexistence principle). (iii) It should promote innovation and competition to increase the overall efficiency and accessibility of the payment system (the innovation and efficiency principle). 4.2 Considering the above principles, the design choices considered for issuing CBDCs are driven mainly by domestic circumstances. There will be no “one size fits all” approach to CBDC. A well-functioning CBDC will require an extremely resilient and secure infrastructure that can be scalable to support users on a massive scale. The design of CBDC is dependent on the functions it is expected to perform, and the design determines its implications for payment systems, monetary policy as well as the structure and stability of the financial system. Given that designs and systems will differ by jurisdictions, so will the risk, which will require significant research by a central bank before implementation. A central bank should have robust means to mitigate any risks to financial stability before any CBDC is issued. 4.3 The key considerations that need to be borne in mind while making a design choice are discussed below. The committee recommended the followings in respect to these issues: 4.3.1 Types of CBDC Based on the usage and the functions performed by the CBDC and considering the different levels of accessibility, CBDC can be demarcated into two broad types viz. general purpose (retail) (CBDC-R) and wholesale (CBDC-W). CBDC-R is potentially available for use by all private sector, non-financial consumers and businesses. In contrast, wholesale CBDCs are designed for restricted access by financial institutions. CBDC-W could be used for improving the efficiency of interbank payments or securities settlement, as seen in Project Jasper (Canada) and Ubin (Singapore). Central banks interested in addressing financial inclusion are expected to consider issuing CBDC-R. Further, CBDC–W has the potential to transform the settlement systems for financial transactions undertaken by banks in the G-Sec Segment, Inter-bank market and capital market more efficient and secure in terms of operational costs, use of collateral and liquiditymanagement. Further, this would also provide coincident benefits such as avoidance of settlement guarantee infrastructure or the need for collateral to mitigate settlement risk. According to a BIS report13, wholesale CBDCs are intended for the settlement of interbank transfers and related wholesale transactions. They serve the same purpose as reserves held at the central bank but with additional functionality. One example is the conditionality of payments, whereby a payment only settles if certain conditions are met. This could encompass a broad variety of conditional payment instructions, going far beyond today's delivery-versus-payment mechanism in real-time gross settlement (RTGS) systems. In effect, wholesale CBDCs could make central bank money programmable, to support automation and mitigate risks. Further, wholesale CBDCs would be implemented on new technology stacks. This clean-slate approach would let wholesale CBDC systems to be designed with international standards in mind to support interoperability. CBDC-W could also be explored for the following: -

Wholesale market for asset classes which are OTC and bilaterally or settled outside CCP arrangements- CPs, CDs, etc. -

Access to retail for buying assets such as G-secs, CPs/CDs, primary auctions etc bypassing the bank account route -

In case of g-secs, if assets are also tokenised, this could be extended to non-residents to investment in domestic asset classes. The adoption will depend on exchanges and trading infrastructure being upgraded and CBDC-W to be integrated with RTGS. The adoption will also depend on whether the cost of CBDC-W settlement less than the cost of existing settlements including liquidity savings, guaranteed, margin funding etc. CBDC-R is an electronic version of cash primarily meant for retail consumption. India is already having a sound payment system with a different array of payment products ranging from RTGS, NEFT to UPI etc. coupled with an exponential increase in digital transactions. The introduction of CBDC-R will provide a safe, central bank instrument with direct access to the Central bank money for payment and settlement. It is also argued that it could also reinforce the resilience of a country’s retail payment systems. CBDC can provide an alternative medium of making digital payments in case of operational and/or technical problems leading to disruption in other payment system infrastructures. CBDC could reduce the concentration of liquidity and credit risk in payment systems (Dyson and Hodgson (2016)). Looking at the different advantages of CBDC-W and CBDC-R, there may be merit in introducing both CBDC-W and CBDC-R. 4.3.2 Role of Central Bank and Other Entities: Who administers the CBDC A key question in the design of a CBDC would be the respective roles of the central bank and the private sector in facilitating access to and use of a CBDC. There are three models for issuance and management of CBDCs across the globe. The key differences lie in the structure of legal claims and the record kept by the central bank. A) Single Tier model - This model is also known as “Direct CBDC Model”. A Direct CBDC system would be one where the central bank is responsible for managing all aspects of the CBDC system including issuance, account-keeping, transaction verification et. al. In this model, the central bank operates the retail ledger and therefore the central bank server is involved in all payments. In this model, the CBDC represents a direct claim on the central bank, which keeps a record of all balances and updates it with every transaction. It provides an advantage of a very resilient system as the central bank has complete knowledge of retail account balances which allows it to honour claims with ease since all the information needed for verification is readily available. The major disadvantage of this model is that it marginalises private sector involvement and hinders innovation in the payment system. This model is designed for disintermediation where central bank interacts directly with the end customers. This model has the potential to disrupt the current financial system and will put additional burden on the central banks in terms of managing customer on-boarding, KYC and AML checks, which may prove difficult and costly to the central bank.  B) Two-Tier Model (Intermediate model) The inefficiency associated with the Single tier model demands that CBDCs are designed as part of a two-tier system, where the central bank and other service providers, each play their respective role. There are two models under the intermediate architecture viz. Indirect model and Hybrid Model. Indirect Model - In the “indirect CBDC” model, consumers would hold their CBDC in an account/ wallet with a bank, or service provider. The obligation to provide CBDC on demand would fall on the intermediary rather than the central bank. The central bank would track only the wholesale CBDC balances of the intermediaries. The central bank must ensure that the wholesale CBDC balances is identical with all the retail balances available with the retail customers. Hybrid Model - In the Hybrid model, a direct claim on the central bank is combined with a private sector messaging layer. The central bank will issue CBDC to other entities which shall make those entities then responsible for all customer-associated activities. Under this model, commercial intermediaries (payment service providers) provide retail services to end users, but the central bank retains a ledger of retail transactions. This architecture runs on two engines: intermediaries handle retail payments, but the CBDC is a direct claim on the central bank, which also keeps a central ledger of all transactions and operates a backup technical infrastructure allowing it to restart the payment system if intermediaries run into insolvency or technical outages. Comparison of three models | Aspect | Direct | Indirect | Hybrid | | Liability | Central Bank | Central Bank | Central Bank | | Issuer | Central Bank | Central Bank issues and intermediaries distribute it | Central Bank Issues and Intermediaries distribute it for retail use | | Operations | Central Bank | Intermediaries | Intermediaries | | Ledger | Central Bank | Intermediaries | Intermediaries as well as Central Bank | | Settlement Finality | Yes | No | Yes | | (Figure 8: Source: RBI Internal) | Considering the merits of different models, the Indirect system may be the most suitable architecture for introduction of CBDC in India. As per the RBI Act, 1934, the Reserve Bank has the sole right to issue bank notes, which has now been amended to include currency in digital form also. Therefore, in this model, RBI will create and issue tokens to authorised entities called Token Service Providers (TSPs) who in turn will distribute these to end-users who take part in retail transactions. The rationale behind the same are as given below: (i) In the entire supply chain, there are a wide range of customer-facing activities where the central bank is unlikely to have a comparative and competitive advantage as compared to banks, especially in an environment where technology is changing rapidly, which inter-alia includes distribution of CBDCs to public, account-keeping services, customer verification such as KYC and adherence to AML/CFT checks, transaction verification, etc. (ii) Banks and other such entities have the expertise and experience to provide these services. (iii) These entities can provide their customers with the ability to transact in and out of CBDC and thus can enrich the customer experience and may facilitate wider adoption of CBDCs. 4.3.3 Instrument Design - Should CBDCs bear interest? The economic design of CBDC could depend on the purpose of the CBDC and the technologies and entities involved. For example, most discussions around retail CBDC envisage it being introduced primarily as a method of payment like cash, with the presumption that it would not bear interest. Remunerated CBDC The payment of (positive) interest would likely to enhance the attractiveness of an instrument that also serves as a store of value. Some proponents support interest bearing CBDCs as it could improve the effectiveness of monetary policy by shifting the transmission leg from overnight money market rate to directly deposit rate (or CBDC as a substitute of deposits), strengthening the pass-through of the central bank’s policy rate to the broader structure of interest rates in the financial system. But, designing a CBDC that moves away from cash-like attributes to a “deposit-like” CBDC could lead to a massive disintermediation in the financial system resulting from loss of deposits by banks, impeding their credit creation capacity in the economy. Further, in such a scenario, banks may be compelled to increase deposit rates, thus increasing their costs of funding and a decrease in Net Interest Income. As a response to this, banks could be motivated to pass on these additional costs to borrowers or resort to engage in riskier activities in search of higher returns. Moreover, banks would need to maintain additional liquidity buffers to support CBDC demand, as access to large central bank and money market liquidity would need to be backed by eligible collaterals. One possible way to mitigate the risk of disintermediation is to impose a cap or limit on individual holdings but these features will reduce the attractiveness and wide acceptability of CBDCs along with adding complexities to the CBDC system. Non – remunerated CBDC If a CBDC is designed to be non-interest bearing, the public would have less incentive to switch from holding bank deposits to CBDC, and the effect of banking disintermediation would then be limited. The Bahamas and China currently do not pay interest on CBDC holdings. In both the cases, the reason is to limit CBDC competing with bank deposits. If there is no interest, CBDC can still be attractive as a medium of payment, even while its attractiveness as a store of value (savings instrument) diminishes. Further, a non- interest bearing CBDCs can avoid a major disruption to banking services and a possible disintermediation of banks. However, there is still a concern expressed in some quarters that there could be a possibility of shifting of some of the current accounts maintained by corporates and business entities with banks in favour of CBDC to gain access to central bank money. We believe that the current account is a relationship based and their association with banks is a function of multiple services offered to them and thus it is anticipated that scale of bank intermediation will be low for such deposits. In a nutshell, the economic design of a CBDC should be least disruptive to the existing financial system. Moreover, CBDCs are electronic form of sovereign currency and should imbibe all the possible features of currency. Since, physical cash does not carry any interest it would be logical to offer Non-Interest bearing CBDCs. Banks would restrain themselves from distributing CBDCs if they find it as a threat to their bank deposits which can hamper credit flows and adoption of CBDCs. Further, to begin with, many jurisdictions have opted to limit the holdings of CBDCs available to the public for transactional purposes (in wallets) to put a cap on the scale of disintermediation, as it is expected to be least disruptive. Trade-off: A more effective CBDC vs more dynamic monetary policy transmission Although a non- interest bearing CBDCs can avoid major disruption to banking services and a possible disintermediation of banks, the trade off with this consideration is that a non- interest bearing CBDC may not improve the monetary policy transmission in India. The trade-off challenge for policy resulting from interest bearing CBDC is between improved interest rate transmission and a clogged credit market resulting from financial disintermediation. Since the interest rate channel of transmission must operate by influencing the credit conditions and financial flows to the productive sectors of the economy, and non-interest bearing CBDC will not hamper the existing transmission dynamics, avoiding any scope for financial disintermediation should be the prime objective while dealing with this trade-off. This can be achieved by setting a conversion limit between deposits or cash to CBDC or paying no interest or lower interest rates on CBDC relative to bank deposits. | 4.3.4 Account-based or token-based? CBDC can be structured as ‘token’ or ‘account’ based or a combination of both. Token vs Account (i) A token-based CBDC system would involve a type of digital token issued by and representing a claim on the central bank and would effectively function as the digital equivalent of a banknote that could be transferred electronically from one holder to another. A token CBDC is a “bearer-instrument” like banknotes, meaning that whoever ‘holds’ the tokens at a given point in time would be presumed to own them. In contrast, an account-based system would require the keeping of a record of balances and transactions of all holders of the CBDC and indicate the ownership of the monetary balances. (ii) Another difference between tokens and accounts is in their verification: a person receiving a token will verify that his ownership of the token is genuine, whereas an intermediary verifies the identity of an account holder. Transactions in account-based system would involve transferring CBDC balances from one account to another and would depend on the ability to verify that a payer had the authority to use the account and that they had a sufficient balance in their account. Transactions in token-based CBDC might only depend on the ability to verify the authenticity of the token (to avoid counterfeits just as in the case of a paper currency) rather than establishing the account holder’s identity. (iii) In an account-based CBDC system, during the initial creation of each CBDC account, the identity of the account holder would need to be verified and from that point onward, payment transactions could be conducted rapidly and securely. By contrast, in a token-based system, the entire chain of ownership of every token must be stored in an encrypted ledger. In case of tokens on distributed ledger, new payment transactions are collected into blocks that must be verified before being added permanently to the ledger. The CBDC-W may be issued in account-based form, as legally, it attempts to offer instant settlement and their legal status is well understood and established. Moreover, the use case of CBDC-W warrants them to be account based to facilitate the transactions. CBDC-R is mainly devised for consumption of common public with features akin to physical cash viz. anonymous, unique serial number etc. A token-based system would ensure universal access – as anybody can obtain a digital signature – and it would offer good privacy by default. Moreover, the token generated will have a unique token number which will enable the detection of counterfeiting of tokens and potentially also the restoration of value if an individual loses the device. Under a token-based CBDC-R regime, users would be able to withdraw digital tokens from banks in the same way they can withdraw physical cash. They would maintain their digital tokens in a wallet and could spend them online or in person or transfer them via an app. The token based CBDC also supports innovation with an ability to include programmable feature that supports efficiency such as standardisation of compliance rules, fraud detection, wrapped CBDC to other use cases in future. Further, token-based CBDC-R can be used to accomplish financial inclusion goals. 4.3.5 Anonymity14 - What degree of privacy would apply and who could hold CBDC? For CBDC to substitute currency as a medium of exchange, it needs to incorporate all the features that physical currency represents – anonymity (that currency transactions can be carried out without maintaining evidence of transacting parties), universality (that currency can be used for any transaction) and finality (that payment of currency unconditionally settles the transaction). Ensuring anonymity for a digital currency particularly represents a challenge, as all digital transactions leave a trail. Clearly, the degree of anonymity would be a key design decision for any CBDC and there has been significant debate on this issue. Most central banks and other observers have, however, noted that the potential for anonymous digital currency to facilitate shadow-economy and illegal transactions, makes it highly unlikely that any CBDC would be designed to fully match the levels of anonymity and privacy currently available with physical cash. An intermediate degree of privacy may be thought of and can also be possible. For example, the European Central Bank (2019) has experimented with the concept of a CBDC with elements of programmable money, by which individuals could be allotted a certain amount of ‘anonymity vouchers’ that could be used for small transactions, with larger transactions still visible to financial intermediaries and the authorities, including those responsible for AML and CFT. Trade-off: Anonymity vs AML/CFT compliance Anonymity is one of the key traits of cash, and the rise of digital payments threatens the lawful or legitimate preference for anonymity as they leave digital trails. The anonymity will expand the user base for CBDC and will increase its acceptability and usage, but it is seen as a potential risk in the digital ecosystem. Anonymity can also be used for illicit purposes and can undermine AML/CFT measures. Anonymity, therefore, poses a policy trade-off—the more anonymous, the larger the risk for illicit use. Considering the potential risks associated with privacy and anonymity, the idea of complete anonymity in digital world is a misnomer. To what extent a Central Bank should allow spending in digital currency to be anonymous is an open question. However, the principle of Managed Anonymity may be followed i.e., “anonymity for small value and traceable for high value,” akin to anonymity associated with physical cash. The importance of protecting personal information and data privacy needs to be considered to foster usability and wider adoption. | 4.4 Fixed Denomination vs minimum Value based CBDCs A token based CBDC may be issued either with minimum value or fixed denominations akin to existing physical currency denominations. The usage of minimum value of token may result in higher volume and, thus, lead to increase in processing time and performance issues. Further, the physical appearance (touch and feel) of cash in India imparts trust to public to undertake cash transactions. The introduction of CBDC with fixed Denomination as in physical currencies in denominations of Rs. 500, 100, 50 etc., shall facilitate in building the same level of trust and experience among public albeit in digital form. This similarity with existing currency is expected to induce wider acceptance and adoption of CBDC. Moreover, the fixed denomination CBDC shall facilitate transactions by way of exchange management of tokens in permissible legal tender of the country with help of TSPs. Therefore, introduction of fixed denomination CBDC is presently considered as preferable taking into account the Indian scenario. 4.5 Summary of Design Features The table below summarises the design features under consideration or deployed by the six central banks. | | Carry Interest or Not | Quantitative Restrictions | Anonymity | Offline | Cross-Border Payments | | Bahamas | No | Yes | For lower tier | Yes/exploring | Future project | | Canada | Undecided | Undecided | Undecided | Exploring | International collaboration | | China | No | Yes | For lower tier | Yes | Experimenting/international collaboration | | ECCU | No | Yes | For lower tier | No | Future project | | Sweden | Undecided | Exploring | Undecided | Exploring | International collaboration | | Uruguay | No | Yes | Yes, but traceble | No | Possible future project | | (Figure:10, Source: IMF FinTech Notes (February 2022)) | 4.6 Preferred Design Choices: snapshot Chapter 5: Technology Considerations for CBDC 5.1 CBDC being digital in nature, technology considerations shall always remain at its core. Technology is what will constitute any CBDC and technology is what will translate the abstract policy objectives to concrete forms. Having discussed the motivations and possible implications of CBDC, it is apt to deliberate on the technology considerations of the digital currency. While the “Why” has been discussed in previous chapters, the current chapter will focus on “How”. The technical principle underlying the deployment of CBDC to achieve the intended objectives may include: -

Strong cybersecurity, technical stability and resilience. -

Sound technical governance The first and fundamental question that needs to be answered is the choice of technology platform. The platform can either be a distributed ledger or a centralised system. In addition to platform choices, other technical considerations shall flow from the policy imperatives. For example, if one of the motivations behind introduction of CBDC is financial inclusion, it should support offline capability. Further, the security aspects of CBDC shall also determine its resilience and will be necessary for robust, secured implementation. The business continuity planning will also need to be embedded in the technology architecture. In the end, the environment and energy intensiveness concerns shall also need to be factored while designing the technology choices. 5.2 Choice of Technology Platform 5.2.1 Platform features CBDC should be developed in India as a large-scale enterprise-class digital platform which may have the following features: -

Highly scalable to support very high volume and rate of transactions without performance degradation. -

Robust to ensure stability of financial ecosystem -

Tamper-proof access control protocols and Cryptography for safety of data, both CBDC and transactional data -

Cross platform support, to allow development of large variety of client applications using CBDC for financial services -

Ability to integrate with other IT platforms in the financial ecosystem must be at the core of platform design -

Configurable workflows for quick implementation of policy level directives issued by RBI from time to time -

Comprehensive administration, reporting, and data analytics utilities -

Highly evolved fraud monitoring framework to prevent occurrence of financial frauds 5.2.2 Technology Architecture Options 5.2.2.1 Large scale digital platforms using traditional client-server architecture have been successfully implemented across the world in the banking, retail, health, and other sectors. These platforms provide all the platform features described in the earlier paragraphs but in the case of CBDC, careful planning is required on account of following key requirements: a) Zero downtime, to keep the economy functioning b) Zero frauds, to prevent destabilization of the economy c) Decentralization, for effective participation of the ecosystem d) Need for confidentiality, authentication, data integrity, and non-repudiation e) High volume and rate of Transactions, will be a key requirement of the ecosystem partners to avoid choking of the CBDC platform resulting in delays in completing financial transactions f) Design for unpredictable workloads, the platform must handle both lean and peak load periods in a cost-effective manner. g) Zero loss due to Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) and other brute cyberattacks h) Mission Critical approach, to meet all the above key requirements 5.2.2.2 DLT or non-DLT The infrastructure selected for implementing CBDC could be based on a conventional centrally controlled database, or on a distributed ledger. Conventional and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT)-based infrastructures often store data multiple times and in separate physical locations. However, the key difference between conventional and DLT based infrastructure lies in how data is updated. In conventional databases, resilience is ensured by storing data over multiple physical nodes, which are controlled by one authoritative central entity, i.e., the top node of the hierarchy. On the other hand, in DLT-based systems, the ledger is usually managed jointly by multiple entities in a decentralised manner and each update needs to be harmonised amongst the nodes of all entities without the requirement of a top node. This consensus mechanism requires additional overhead which is the primary reason why DLTs enables lower transactions than conventional architectures. Given the above, DLT at this point of time, is not considered suitable technology except in very small jurisdictions, given the probable low volume of data throughput. However, DLT could be considered for the indirect or hybrid CBDC architecture. Further, it may also be possible that some layers of the CBDC tech stack can be on centralized system and remaining on distributed networks. The choice of tech architecture shall also factor in the resource intensiveness and energy efficiency associated with the solutions. 5.3 Scalability It is expected that every CBDC project will start with a limited scale pilot and would subsequently be scaled up at population scale. Despite being a limited pilot, it will always be essential that the system should be designed so that it can be extended in the future and used in production or large-scale deployments. To begin with, the system should be able to accommodate the likely volume of transactions (Billions per day) involved in a large-scale deployment. The architecture should not be redesigned or reworked to achieve this. Additionally, the system should be designed so that it can be expanded in the future without needing to be redesigned or reworked. 5.4 Trusted Environment It is essential that entire lifecycle of CBDC should be within an end-to-end trusted environment. It can be achieved by ensuring that Double-spend and malicious token creation or manipulation is avoided, monitored and checked regularly. It also needs to be confirmed that data is shared only with the relevant parties and does not need to be shared across the whole network (distributed or otherwise) for verification. Further, systemic checks through third party validation should ensure that in case of a token system, only such tokens issued by the Central bank are circulating in the ecosystem. Additionally, a competent party should be able to verify identity information before a participant is allowed to join the CBDC network. Policy related Tech Considerations 5.5 Recoverability In case of account-based models, the issue of recoverability does not arise as the identity of user shall always be available where the account is held. In the case of token-based models, based on whether CBDCs will be recoverable or not, the system can support two types of wallets based on User Consent: -