Before she was killed, prominent indigenous activist Berta Caceres wrote a letter to Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples.

“The threat to Rio Blanco has returned due to this new onslaught by DESA Corporation,” Caceres wrote in Spanish in Oct. 2015. She then asked Tauli-Corpuz—whose UN role is to serve as an expert “investigator” of abuses against indigenous people—to visit her community in Honduras, and investigate “the severe violation of individual and collective human rights of indigenous peoples in our country,” they perceived from the development of the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam by the company Desarrollos Energéticos S.A. (DESA).

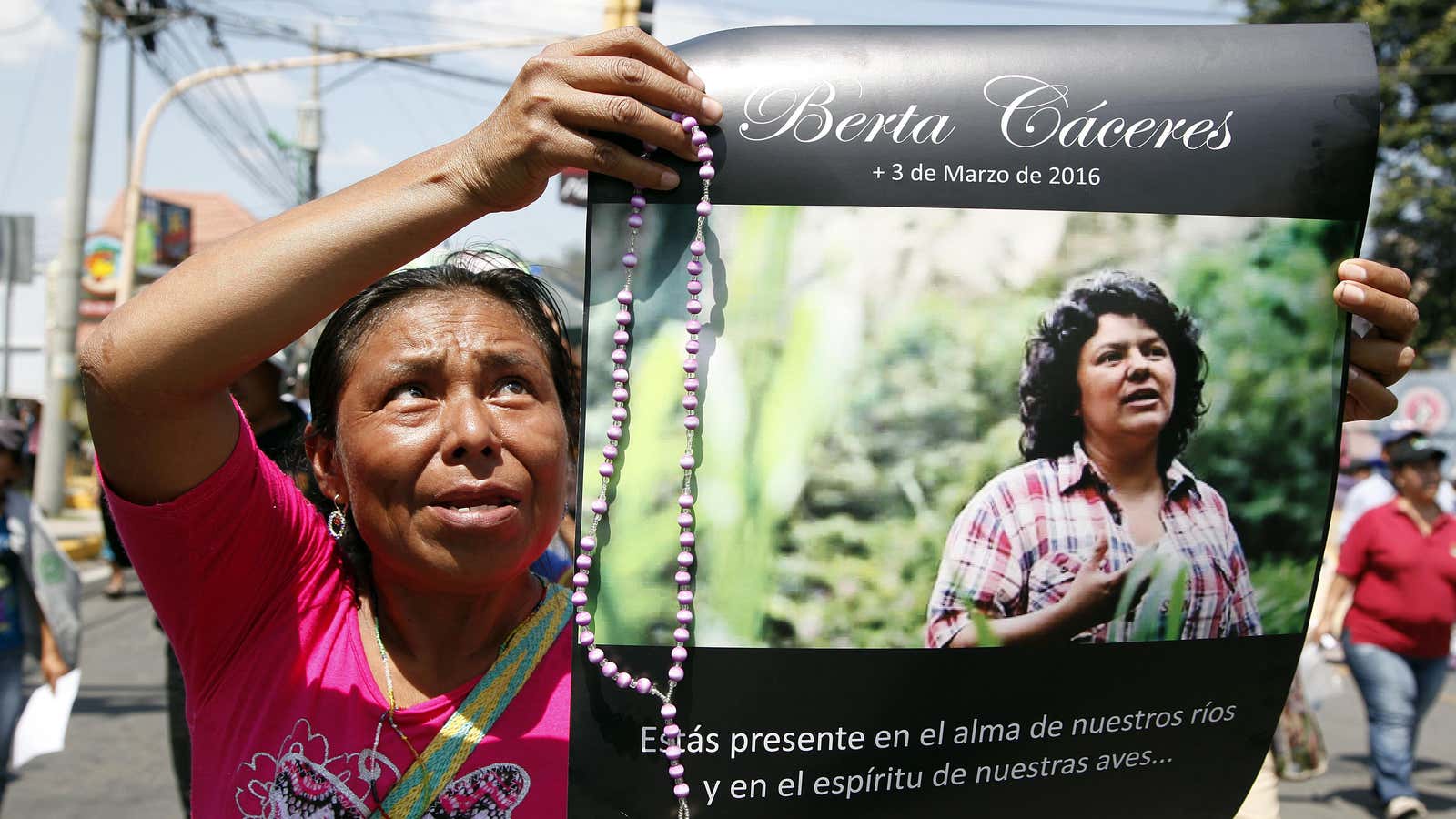

In March 2016, Caceres was shot and killed in her home. Five people were charged with her murder—including two men linked to DESA: a man named as a “manager for social and environmental matters” in a statement by DESA and a private security guard who had been employed by the company.

“This is not a safe world, especially for indigenous peoples,” says Tauli-Corpuz. “You cannot hide.” For years, fossil fuel extractors have been criticized for harming local communities; now, as the world moves towards renewable energy, indigenous people are facing threats from those seeking to make money in the new, green economy.

After the global climate agreement brokered in Paris last year, investment in renewable energy is surging. Last year, the number of new renewable energy installations outpaced the number of new fossil fuel installations globally for the first time ever.

Though they seem inherently progressive, renewable energy projects—from hydroelectric dams to wind farms—can displace indigenous groups from their land and interrupt their traditions and livelihoods.

Eniko Horvath, a senior researcher at the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre in London, says Caceres isn’t the only human rights advocate to be threatened or killed for resisting a green power project. “Despite the increasing investment [in renewables] we’ve been seeing, we didn’t see a real conversation around the human rights impacts that these companies are having,” Horvath says.

This year, the Centre released a report on responsible renewable energy. They reached out to 50 renewable energy companies about their approach to human rights, and only five said they’d committed to following the internationally recognized standard established in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which prohibits resource extraction, development or other investment projects on native land without the free, prior and informed consent of the indigenous community.

The problem is the conflict of interest inherent in green energy development, says Richard Taylor, chief executive of the International Hydropower Association, a membership organization representing corporations, engineers, and researchers working in the hydropower sector. “Many developers are coming in with a perspective of getting a return on investment,” says Taylor. “They’re not necessarily the best people to do a rigorous preparation of a project; however, the expectation is on them. So there is this conflict of interest about how much effort goes into the preparation of a project.”

In 2010, the World Bank and European Investment Bank financed the expansion of geothermal energy production in Kenya and the construction of a 140-megawatt power station on land in the Rift Valley traditionally occupied by the Maasai people. Then in 2014, Maasai leaders filed a complaint against the World Bank, alleging the community was pushed off their lands without proper consultation and resettled into a smaller area that could not support their livestock, the source of their livelihood as pastoralists. “You are evicted because it is in the national interest to have access to energy for all,” says Edna Kaptoyo of the Indigenous Information Network, a Kenyan NGO. The World Bank eventually conceded it failed to adequately communicate with the community in their language, and that they were not fairly compensated for the loss of their land and livelihoods.

But it’s complicated. Indigenous leaders are fighting for land rights and against corporate “green-grabbing”—but they do genuinely want a just transition to renewable energy. Indigenous groups are considered a “frontline community” by environmentalists—they often experience the first and worst effects of climate change. For generations, they have followed weather and climate patterns for their agriculture and other means of livelihood. When these patterns become less reliable, climate change can have severe economic, social, and health impacts.

“For indigenous peoples, renewable energy has both its good and bad sides. The good thing is we cannot deny that it can contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” says Tauli-Corpuz.

Human rights defenders like Tauli-Corpuz and Horvath contend that native peoples’ voices need to be included in development projects meant to mitigate the effects of climate change, so that the vulnerabilities that result from the uneven power dynamic between large fossil fuel companies and local communities aren’t replicated in the shift towards green energy.

“When solutions to climate change are brought to [indigenous communities] they are not consulted nor is their consent obtained,” says Tauli-Corpuz. “I’m here to make sure human rights will be included.” As the Paris agreement was being negotiated last year, Tauli-Corpuz and other advocates successfully pushed for human rights and indigenous peoples’ rights to be specifically named within the text.

Winnie Jimis, a member of the Orang Asli tribes of peninsular Malaysia, is fighting another dam project in Sabah, Borneo, by working as the project coordinator for the community organization Community-Led Environmental Awareness for our River. “We don’t want it,” says Jimis. “It’s going to drown a settlement of our people. There are schools and clinics in the village. It will drown the forest.” The proposed Kaiduan Dam would submerge up to 12 sq km of forest, and the project is already mired in controversy after two senior water officials were arrested on graft charges in connection to the dam and other federal projects.

As an alternative, Jimis advocates micro-hydro projects, like the small hydroelectric dam in Long Lawen village in Upper Bakun, Malaysia. The Orang Asli there have used the micro-dam to power lights and refrigeration for a community of about 350 people since 2000. The community received about $53,000 from several Malaysian NGOs to fund the project.

Bigger picture, some environmentalists have pushed to redefine what gets categorized as “renewable energy” in an effort to limit damage on indigenous communities. The Sierra Club, for example, supports small-scale dam efforts, but condemns large-scale hydropower projects because of the damage they inflict on wildlife and watersheds. Most influential international and funding bodies, however, still consider large-scale hydropower renewable, including the World Bank and the US House Committee on Natural Resources.

This year, Tauli-Corpuz presented a report to the UN General Assembly on the violation of indigenous peoples’ rights in the name of conservation. She also submitted a report to the Human Rights Council on the state of indigenous peoples in Honduras, condemning the killing of Caceres and calling for the Honduran government to reconsider its contract with DESA and revoke its licenses and permits.

“For me, the death of Berta [Caceres] is really very devastating and it symbolizes a lot of what indigenous peoples go through on a day-to-day basis,” says Tauli-Corpuz.

This story was reported with funding support from The GroundTruth Project, a media nonprofit focused on international enterprise journalism.