Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy

Updated 2 July 2021

Foreword from the Prime Minister

When we began the Integrated Review in early 2020, we could not have anticipated how a coronavirus would trigger perhaps the greatest international crisis since the Second World War, with tragic consequences that will persist for years to come. COVID-19 has reminded us that security threats and tests of national resilience can take many forms.

Thanks to the fortitude of the British people and the monumental efforts of our NHS, the UK is emerging from the pandemic with renewed determination and optimism. Our journey to recovery has already begun and we are resolved to build back better, ensuring that we are stronger, safer and more prosperous than before. Yet if we are to escape the malign effect of the virus, the race to vaccinate and therefore protect people cannot stop at national borders. Hence the UK has joined other countries in the COVAX initiative to extend this campaign across the globe.

Having left the European Union, the UK has started a new chapter in our history. We will be open to the world, free to tread our own path, blessed with a global network of friends and partners, and with the opportunity to forge new and deeper relationships. Our Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU gives us the freedom to do things differently and better, both economically and politically. In the years ahead, agility and speed of action will enable us to deliver for our citizens, enhancing our prosperity and security.

My vision for the UK in 2030 sets high ambitions for what this country can achieve. The Union between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland has proved its worth time and again, including in this pandemic. It is our greatest source of strength at home and abroad. Our country overflows with creativity in the arts and sciences: the wellsprings of unique soft power that spans the globe.

Few nations are better placed to navigate the challenges ahead, but we must be willing to change our approach and adapt to the new world emerging around us. Open and democratic societies like the UK must demonstrate they are match-fit for a more competitive world. We must show that the freedom to speak, think and choose – and therefore to innovate – offers an inherent advantage; and that liberal democracy and free markets remain the best model for the social and economic advancement of humankind.

History has shown that democratic societies are the strongest supporters of an open and resilient international order, in which global institutions prove their ability to protect human rights, manage tensions between great powers, address conflict, instability and climate change, and share prosperity through trade and investment. That open and resilient international order is in turn the best guarantor of security for our own citizens.

To be open, we must also be secure. Protecting our people, our homeland and our democracy is the first duty of any government, so I have begun the biggest programme of investment in defence since the end of the Cold War. This will demonstrate to our allies, in Europe and beyond, that they can always count on the UK when it really matters. We will exceed our manifesto and NATO spending commitments, with defence spending now standing at 2.2% of GDP, and drive forward a modernisation programme that embraces the newer domains of cyber and space, equipping our armed forces with cutting-edge technology. And we will continue to defend the integrity of our nation against state threats, whether in the form of illicit finance or coercive economic measures, disinformation, cyber-attacks, electoral interference or even – three years after the Salisbury attack – the use of chemical or other weapons of mass destruction.

As the attacks in Manchester, London and Reading have sadly demonstrated, the terrorist threat in the UK remains all too real – whether Islamist-inspired, Northern Ireland-related or driven by other motivations. Our security and intelligence agencies and law enforcement community work around the clock to stop would-be terrorists in their tracks, disrupting 28 planned attacks since 2017. We will continue to invest in this essential work, through increased funding for the intelligence agencies and Counter Terrorism Policing in 2021-22 and our drive to recruit an extra 20,000 police officers. And we will maintain constant vigilance in protecting British citizens from serious and organised crime.

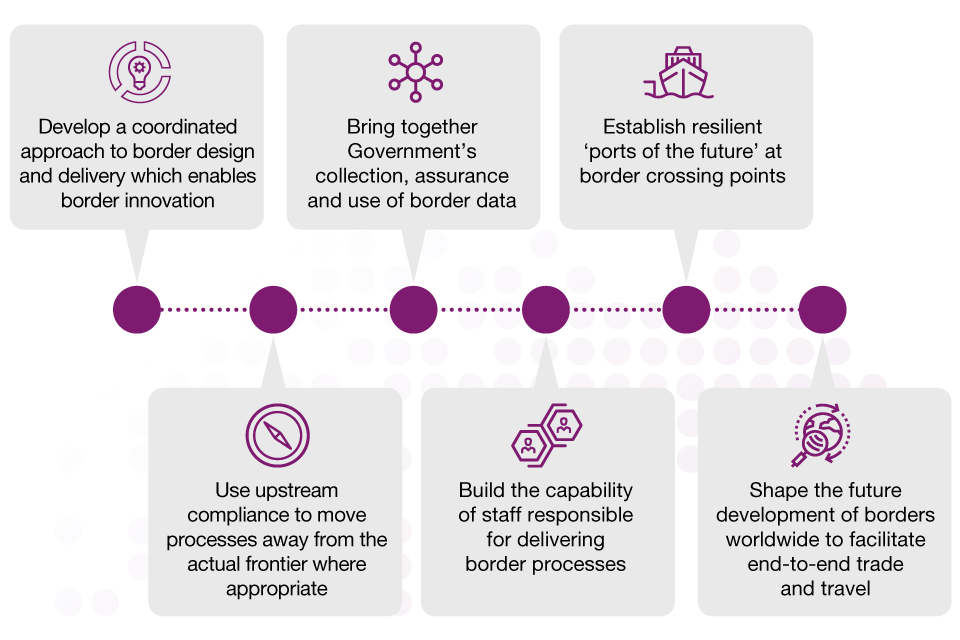

We will also bring to bear new capabilities such as the Counter-Terrorism Operations Centre and the National Cyber Force. Learning from the pandemic, we will bolster our national resilience with a new Situation Centre at the heart of Government, improving our use of data and our ability to anticipate and respond to future crises. And we will deliver our goal of having the most effective border in the world by 2025, embracing innovation, simplifying the process for traders and travellers, and improving the security and biosecurity of the UK.

Keeping the UK’s place at the leading edge of science and technology will be essential to our prosperity and competitiveness in the digital age. Our aim is to have secured our status as a Science and Tech Superpower by 2030, by redoubling our commitment to research and development, bolstering our global network of innovation partnerships, and improving our national skills - including by attracting the world’s best and brightest to the UK through our new Global Talent Visa. We will lay the foundations for long-term prosperity, establishing the UK as a global services, digital and data hub by drawing on our nation’s great strengths in digital technologies, and attracting inward investment.

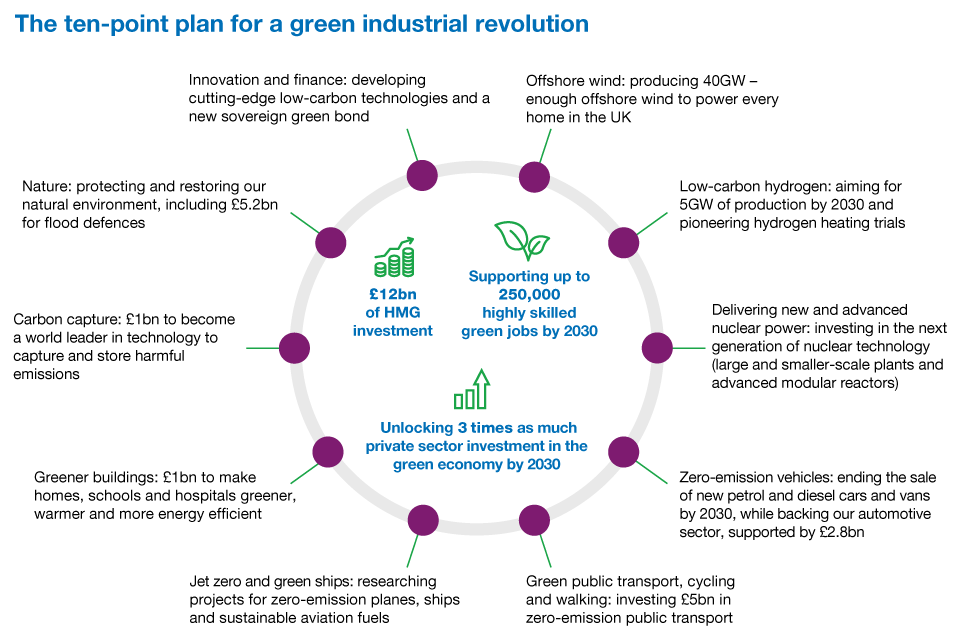

In 2021 and beyond, Her Majesty’s Government will make tackling climate change and biodiversity loss its number one international priority. Under my chairmanship, the UN Security Council recently held its first ever high-level meeting on the impact of climate change on peace and security. The UK was the first advanced economy to set a net zero target for 2050. We will now begin an unprecedented programme of new investment, taking forward our ten-point plan for a green industrial revolution by funding British research and development in green technologies, and helping the developing world with the UK’s International Climate Finance.

The creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office is the springboard for all our international efforts, integrating diplomacy and development to achieve greater impact and address the links between climate change and extreme poverty. The UK will remain a world leader in international development and we will return to our commitment to spend 0.7% of gross national income on development when the fiscal situation allows. And we will maintain the other vital instruments of our influence overseas, such as our global diplomatic network and the British Council, driving forward campaigns for girls’ education and religious and media freedom.

British leadership in the world in 2021

2021 will be a year of British leadership, setting the tone for the UK’s international engagement in the decade ahead, through our presidency of the G7 and the Cornwall summit in June, the Global Partnership for Education, which we will co-host with Kenya in July, and culminating in the 26th UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November, in partnership with Italy.

In 2021 the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, one of the two largest warships ever built for the Royal Navy, will lead a British and allied task group on the UK’s most ambitious global deployment for two decades, visiting the Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific. She will demonstrate our interoperability with allies and partners – in particular the United States – and our ability to project cutting-edge military power in support of NATO and international maritime security. Her deployment will also help the Government to deepen our diplomatic and prosperity links with allies and partners worldwide.

I am profoundly optimistic about the UK’s place in the world and our ability to seize the opportunities ahead. The ingenuity of our citizens and the strength of our Union will combine with our international partnerships, modernised armed forces and a new green agenda, enabling us to look forward with confidence as we shape the world of the future.

The Prime Minister’s vision for the UK in 2030

A stronger, more secure, prosperous and resilient Union

The United Kingdom will be a beacon of democratic sovereignty and one of the most influential countries in the world, tackling the issues that matter most to our citizens through our actions at home and overseas.

Our Union will be more secure and prosperous, with the benefits of growth and opportunity shared between all our citizens, wherever they live in the UK.

We will have built back better from COVID-19 with a strong economic recovery and greater national resilience to threats and hazards in the physical and digital worlds.

We will be better-equipped for a more competitive world – defending our democratic institutions and economy from state threats, terrorists and organised crime groups, while embracing innovation in science and technology to boost our national prosperity and strategic advantage.

A problem-solving and burden-sharing nation with a global perspective

The UK will meet the responsibilities that come with our position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. We will play a more active part in sustaining an international order in which open societies and economies continue to flourish and the benefits of prosperity are shared through free trade and global growth.

We will sit at the heart of a network of like-minded countries and flexible groupings, committed to protecting human rights and upholding global norms. Our influence will be amplified by stronger alliances and wider partnerships – none more valuable to British citizens than our relationship with the United States.

We will continue to be the leading European Ally within NATO, bolstering the Alliance by tackling threats jointly and committing our resources to collective security in the Euro-Atlantic region. As a European nation, we will enjoy constructive and productive relationships with our neighbours in the European Union, based on mutual respect for sovereignty and the UK’s freedom to do things differently, economically and politically, where that suits our interests.

By 2030, we will be deeply engaged in the Indo-Pacific as the European partner with the broadest, most integrated presence in support of mutually-beneficial trade, shared security and values. We will be active in Africa, in particular in East Africa and with important partners such as Nigeria. And we will have thriving relationships in the Middle East and the Gulf based on trade, green innovation and science and technology collaboration, in support of a more resilient region that is increasingly self-reliant in providing for its own security.

Creating new foundations for our prosperity

By 2030, the UK will continue to lead the advanced economies of the world in green technology as part of our wider international action in tackling climate change and biodiversity loss. We will be firmly on the path to achieving global net zero carbon emissions, having reduced our own national emissions by at least 68% compared to 1990 levels. We will also have protected at least 30% of our land and sea to support the recovery of nature.

We will be recognised as a Science and Tech Superpower, remaining at least third in the world in relevant performance measures for scientific research and innovation, and having established a leading edge in critical areas such as artificial intelligence.

We will be at the forefront of global regulation on technology, cyber, digital and data – to protect our own and fellow democracies and to bolster the UK’s status as a global services, digital and data hub, maximising the commercial and employment opportunities for the British people.

The UK will be a magnet for international innovation and talent, attracting the best and brightest from overseas through our points-based immigration system. Every part of the UK will enjoy the benefits of long-term investment in research and development, education and our cultural institutions.

Adapting to a more competitive world: our integrated approach

The UK will continue to be renowned for our leadership in security, diplomacy and development, conflict resolution and poverty reduction. Our cooperation will be highly prized around the world and we will be a model for an integrated approach to tackling global challenges, integrating our resources for maximum effect.

As a maritime trading nation, we will be a global champion of free and fair trade. We will continue to ensure that the openness of our economy – to the free flow of trade, capital, data, innovation and ideas – is an advantage by protecting ourselves and our allies from corruption, manipulation, exploitation or the theft of our intellectual property.

Our diplomatic service, armed forces and security and intelligence agencies will be the most innovative and effective for their size in the world, able to keep our citizens safe at home and support our allies and partners globally. They will be characterised by agility, speed of action and digital integration – with a greater emphasis on engaging, training and assisting others.

We will remain a nuclear-armed power with global reach and integrated military capabilities across all five operational domains. We will have a dynamic space programme and will be one of the world’s leading democratic cyber powers. Our diplomacy will be underwritten by the credibility of our deterrent and our ability to project power.

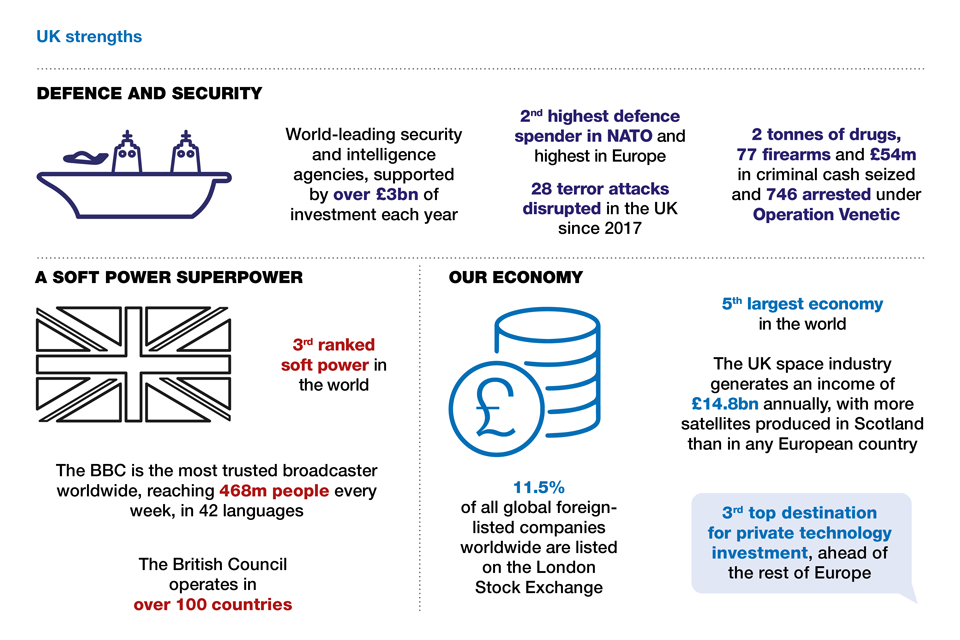

The image above consists of text with icons showing areas where the UK is world-leading.

- Defence and security: World-leading security and intelligence agencies, supported by over; £3bn of investment each year; 2nd highest defence spender in NATO and highest in Europe; 28 terror attacks disrupted in the UK since 2017; 2 tonnes of drugs, 77 firearms and £54m in criminal cash seized and 746 arrested under Operation Venetic.

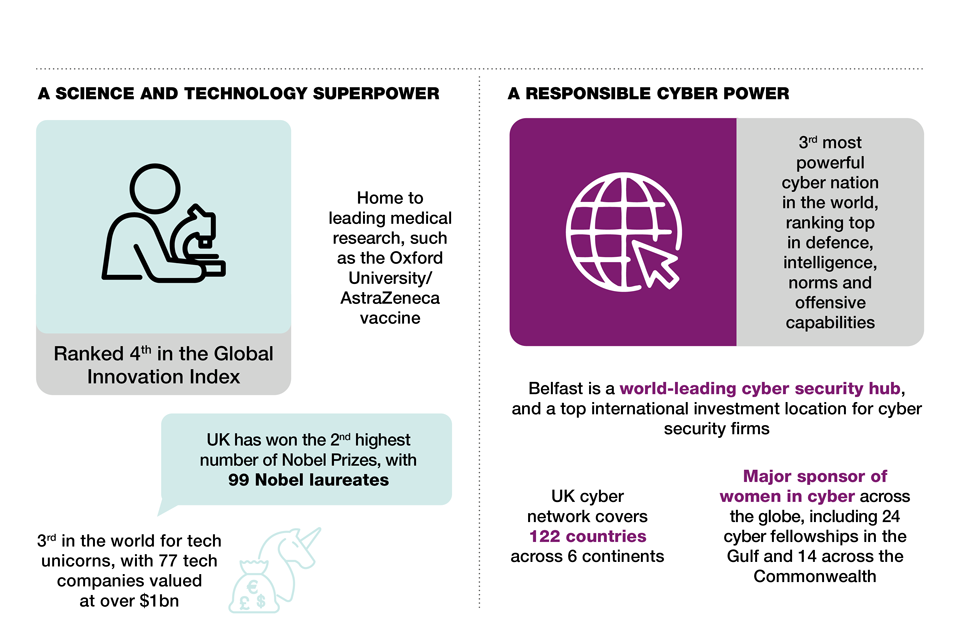

- A science and technology superpower: Ranked 4th in the Global Innovation Index; Home to leading medical research, such as the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine; UK has won the 2nd highest number of Nobel Prizes, with 99 Nobel laureates; 3rd in the world for tech unicorns, with 77 tech companies values at over $1bn

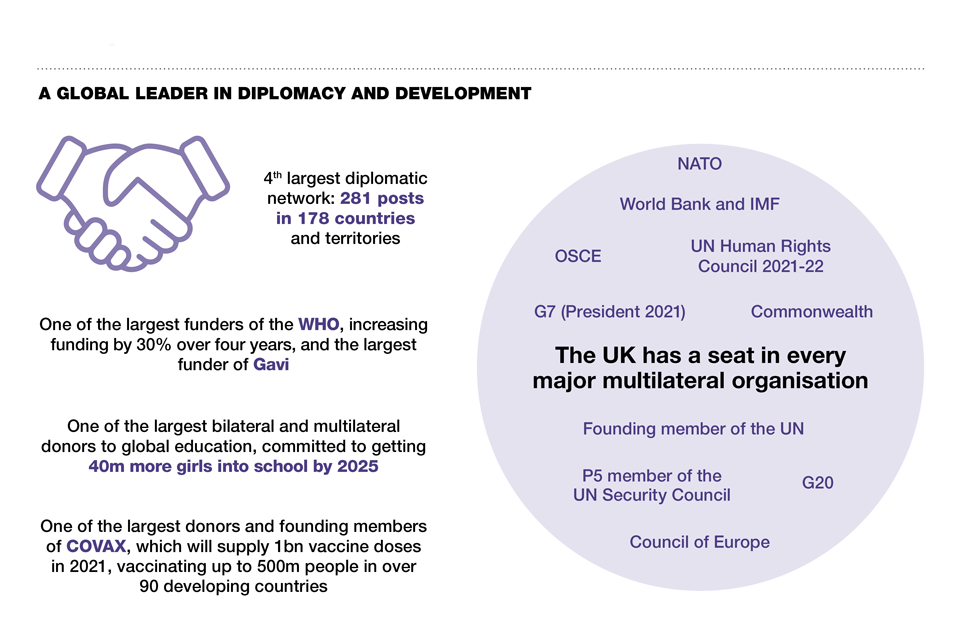

- A global leader in diplomacy and development: 4th largest diplomatic network: 281 posts in 178 countries and territories; One of the largest funders of the WHO, increasing funding by 30% over four years, and the largest funder of Gavi; One of the largest bilateral and multilateral donors to global education, committed to getting 40m more girls into school by 2025; One of the largest donors and funding members of COVAX, which will supply 1bn vaccine doses in 2021, vaccinating up to 500m people in over 90 developing countries; The UK has a seat in every major multilateral organisation: NATO, World Bank and IMF, OSCE, UN Human Rights Council in 2021-22, G7 (President 2021), Commonwealth, Founding member of the UN, P5 member of the UN Security Council, G20, Council of Europe

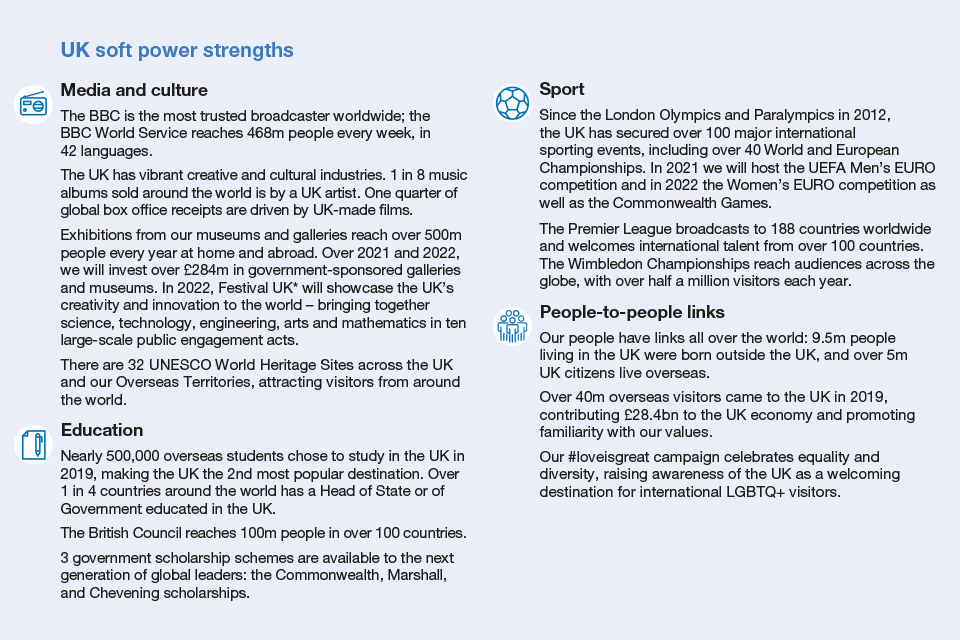

- A soft power superpower: 3rd ranked soft power in the world; The BBC is the most trusted broadcaster worldwide, reaching 468m people every week, in 42 languages; The British Council operates in over 100 countries

- Our economy: 11.5% of all global foreign-listed companies worldwide are listed on the London Stock Exchange; 5th largest economy in the world; The UK space industry generates an income of £14.8bn annually, with more satellites produced in Scotland than any European country; 3rd top destination for private technology investment, ahead of the rest of Europe

- A responsible cyber power: 3rd most powerful cyber nation in the world, ranking top in defence, intelligence, norms and offensive capabilities; Belfast is a world-leading cyber security hub, and a top international investment location for cyber security firms; UK cyber network covers 122 countries across 6 continents; Major sponsor of women in cyber across the globe, including 24 cyber fellowships in the Gulf and 14 across the Commonwealth

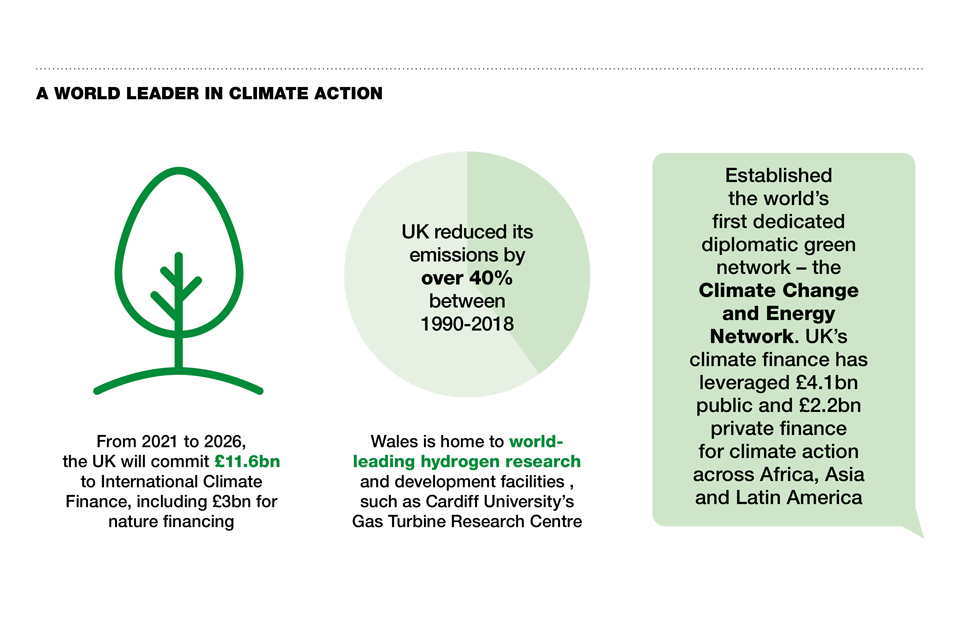

- A world leader in climate action: From 2021 to 2026, the UK will committee £11.6bn to International Climate Finance, including £3bn for nature financing; UK reduced its emissions by over 40% between 1990-2018; Wales is home to world-leading hydrogen research and development facilities, such as Cardiff University’s Gas Turbine Research Centre; Established the world’s first dedicated diplomatic green network - the Climate Change and Energy Network. UK’s climate finance has leveraged £4.1bn public and £2.2bn private finance for climate action across Africa, Asia and Latin America

Overview

The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (Integrated Review) concludes at an important moment for the United Kingdom. The world has changed considerably since the 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review, as has the UK’s place within it. Our departure from the European Union (EU) provides a unique opportunity to reconsider many aspects of our domestic and foreign policy, building on existing friendships but also looking further afield. We must exploit the freedom that comes with increased independence, such as the ability to forge new free trade deals. We must also do more to adapt to major changes in the world around us, including the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific region. Our ability to cooperate more effectively with others, particularly like-minded partners, will become increasingly important to our prosperity and security in the decade ahead.

At the heart of the Integrated Review is an increased commitment to security and resilience, so that the British people are protected against threats. This starts at home, by defending our people, territory, critical national infrastructure (CNI), democratic institutions and way of life – and by reducing our vulnerability to the threat from states, terrorism and serious and organised crime (SOC).

In strengthening our homeland security, we will build on firm foundations in counter-terrorism, intelligence, cyber security and countering the proliferation of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons. We will seek to match this excellence in other areas, through enhanced capabilities and appropriate legal powers that equip us to meet rapidly changing threats. We will also ensure that science and technology (S&T) is elevated to the highest importance as a component of our national security, with a particular emphasis on growing our cyber power.

In keeping with our history, the UK will continue to play a leading international role in collective security, multilateral governance, tackling climate change and health risks, conflict resolution and poverty reduction. We accept the risk that comes with our commitment to global peace and stability, from our tripwire NATO presence in Estonia and Poland to on-the-ground support for UN peacekeeping and humanitarian relief. Our commitment to European security is unequivocal, through NATO, the Joint Expeditionary Force and strong bilateral relations. There are few more reliable and credible allies around the world than the UK, with the willingness to confront serious challenges and the ability to turn the dial on international issues of consequence.

The Integrated Review also signals a change of approach. Over the last decade, UK policy has been focused on preserving the post-Cold War ‘rules-based international system’ which has greatly benefited the UK and other nations. Today, however, the international order is more fragmented, characterised by intensifying competition between states over interests, norms and values. A defence of the status quo is no longer sufficient for the decade ahead.

The Integrated Review therefore recognises the need for a sharper and more dynamic focus in order to: adapt to a more competitive and fluid international environment; do more to reinforce parts of the international architecture that are under threat; and shape the international order of the future by working with others. In particular, we will increase our efforts to protect open societies and democratic values where they are being undermined; and to seek good governance and create shared rules in frontiers such as cyberspace and space.

Our foreign policy rests on strong domestic foundations, in particular our security, resilience and the strength of our economy. It also, crucially, depends on a bond of trust with the British people. Polling in the UK shows deep reserves of faith in bodies like the UN and NATO and the pillars of British defence such as the armed forces and the nuclear deterrent. This is bolstered by high levels of trust in the power of S&T to tackle domestic and international challenges, as we have seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet the international order is only as robust, resilient and legitimate as the states that comprise it. Liberal democracies must do more to prove the benefits of openness – free and fair trade, the flow of capital and knowledge – to populations that have grown sceptical about its merits or been inadequately protected in the past from the downsides of globalisation. This means tackling the priority issues – health, security, economic well-being and the environment – that matter most to our citizens in their everyday lives. In the years ahead, our national security and international policy must do a better job of putting the interests and values of the British people at the heart of everything we do.

The Integrated Review

This publication sets out the principal conclusions of the Integrated Review. It comprises:

- The Prime Minister’s vision for the UK in 2030, from which the other outputs of the Integrated Review flow.

- The Government’s current assessment of the major trends that will shape the national security and international environment to 2030.

- A Strategic Framework that establishes the Government’s overarching national security and international policy objectives, with priority actions, to 2025.

- An outline of the approach we will take to implementing the Strategic Framework.

- A list of Spending Review (SR) 2020 decisions that support the Integrated Review, and a description of our use of evidence and the programme of domestic and international engagement which supported our work.

The document is intended as a guide for action for those responsible for aspects of national security and international policy across government, including in departments that would not previously have been considered part of the national security community. It will also inform spending decisions to be taken in future SRs.

The findings of the Integrated Review are publicly available so that the British people can understand how the Government will seek to protect and promote their interests and values. Given the Review’s strong emphasis on the need to work with others, we are also aware that it will be of interest to our allies and partners, especially in identifying the UK’s long-term objectives following our departure from the EU.

Our interests and our values: the glue that binds the Union

The Government’s first and overriding priority is to protect and promote the interests of the British people through our actions at home and overseas. The most important of these interests are:

- Sovereignty: the ability of the British people to elect their political representatives democratically in line with their constitutional traditions, and to do so free from coercion and manipulation. This encompasses the ability of citizens to protect their individual sovereignty within the rule of law, ensuring that their rights and liberties are protected, including online.

- Security: the protection of our people, territory, CNI, democratic institutions and way of life. Ensuring security in today’s world involves a growing range of activities: from tackling threats from states and non-state actors such as terrorists and organised crime groups; to building societal resilience so that we are better able to withstand risks and unexpected shocks, including future environmental and global health emergencies.

- Prosperity: the ability of the British people to enjoy a high level of economic and social well-being, supporting their families and seizing opportunities to improve their lives. This Government believes that true prosperity depends on the levelling-up of opportunity and doing more to share the benefits of economic growth across the UK. It also believes that our prosperity and security are mutually reinforcing.

These shared interests bind together the citizens of the United Kingdom, along with our Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, giving us an advantage in an increasingly competitive global environment and a distinctive and influential voice in the world. It is as the United Kingdom that we boast armed forces with global reach and have one of the most extensive diplomatic networks in the world, promoting British interests and providing round-the-clock consular assistance to British nationals abroad. It is by combining the resources of our Union and pooling the expertise of our citizens in areas such as science and health that we are able to respond to global challenges and project our influence overseas. It is as the United Kingdom that in 2021 we will host the G7 in Cornwall and 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow.

The Union is also bound by shared values that are fundamental to our national identity, democracy and way of life. These include a commitment to universal human rights, the rule of law, free speech and fairness and equality. The same essential values will continue to guide all aspects of our national security and international policy in the decade ahead, especially in the face of rising authoritarianism and the persistence of extremist ideologies. They are also expressed through our support for climate action and the UK’s leadership in poverty reduction around the world.

In most cases, the UK’s interests and values are closely aligned. A world in which democratic societies flourish and fundamental human rights are protected is one that is more conducive to our sovereignty, security and prosperity as a nation. In pursuing our goals to 2030, we will seek to make steady progress towards the protection and promotion of these values and democracy around the world.

At the same time, our approach will be realistic and adapted to circumstances. Our ability to tackle transnational challenges, from security to climate change, will depend on our capacity to work with a wide range of partners across the world, including those who do not necessarily share the same values.

The Government’s approach so far: Global Britain in action

The UK is a European country with global interests, as an open economy and a maritime trading nation with a large diaspora. Our future prosperity will be enhanced by our economic connections with dynamic parts of the world such as the Indo-Pacific, Africa and the Gulf, as well as trade with Europe. The precondition for Global Britain is the safety of our citizens at home and the security of the Euro-Atlantic region, where the bulk of the UK’s security focus will remain. As we look further afield, the future success of Global Britain requires us to understand the precise nature and extent of British strengths and the integrated offer we bring in other parts of the world. It is an approach that puts diplomacy first. As we engage more in the Indo-Pacific, for example, we will adapt to the regional balance of power and respect the interests of others – and seek to work with existing structures such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

What Global Britain means in practice is best defined by actions rather than words. The fundamentals of this Government’s approach to national security and international policy are reflected in the actions we have taken since the 2019 general election. They demonstrate an active approach to delivering in the interests of the British people: sustaining the UK’s openness as a society and economy, underpinned by a shift to a more robust position on security and deterrence. This runs alongside a renewed commitment to the UK as a force for good in the world - defending openness, democracy and human rights - and an increased determination to seek multilateral solutions to challenges like climate change and global health crises, as seen in our response to COVID-19.

For example, in seeking multilateral solutions, we have used the UK’s convening power on a range of issues across security, trade and development, including at the NATO Leaders Meeting of December 2019 and the Africa Investment Summit of January 2020. Under our ambitious environmental agenda, we have set a net zero target for 2050 and increased our commitment to International Climate Finance (ICF) to £11.6 billion. The UK also played a central role in negotiating the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature adopted in September 2020, committing world leaders to urgent action to reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. These efforts have set up our year of leadership in 2021.

We have also led international efforts in response to COVID-19, under which we have:

- Hosted the Global Vaccine Summit in June 2020 and reinforced our position as the largest donor to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

- Committed up to £548 million to COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) to help provide developing countries with 1 billion doses of the vaccine in 2021. We will also send the majority of any future surplus coronavirus vaccines from our supply to the COVAX scheme.

- Launched a five-point plan at the UN General Assembly to protect the world from future pandemics.

- Established an informal network of government, industry and academics to advise the G7 on accelerating the development and deployment of vaccines for new pathogens in future.

- Offered our expertise in genome sequencing to support other countries in tracking new variants, building on the work of British researchers in sequencing 50% of the global database of coronavirus genomes. The findings of the UK’s Recovery Trial - the world’s largest clinical trial for COVID-19 treatments - have also prevented over a million deaths worldwide.

In strengthening our defence and security, and to play our part in burden-sharing with allies, we have:

- Made the biggest sustained increase in defence spending since the end of the Cold War, exceeding NATO’s 2% spending guideline and strengthening our most important alliance.

- Deployed 300 UK troops to Mali in December 2020 to support the UN’s peacekeeping mission, providing highly-specialised reconnaissance capability.

- Increased funding for counter-terrorism (CT) policing and introduced new legislation to improve our tools for fighting terrorism and state threats, including the Covert Human Intelligence Source Act, the Counter-Terrorism and Sentencing Bill and the National Security and Investment Bill.

- Made a significant breakthrough in the fight against SOC in June 2020, when we infiltrated the encrypted communications of criminals under Operation Venetic - the UK’s largest ever law enforcement operation.

- Disrupted cyber-attacks targeting vital national infrastructure, publicly attributing attacks to state actors where we had compelling evidence to do so.

- Published a pioneering ethical framework in February 2021 to guide the responsible use of artificial intelligence (AI) by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) across its missions - from tackling SOC to disrupting state-based disinformation campaigns.

- Demonstrated global leadership on reducing space threats, working with like-minded nations to deliver a UN General Assembly resolution that reshapes the international debate on threats to the space systems on which we rely.

As part of our efforts to defend human rights and support vulnerable people, we have:

- Introduced a new system of ‘Magnitsky’ sanctions to target human rights violators and abusers around the world. We were the first European country to announce sanctions against the regime in Belarus in September 2020.

- Offered British Nationals (Overseas) and their eligible family members the right to live and work in the UK, putting them on a path to British citizenship, when China breached a legally-binding agreement and imposed a repressive national security law on Hong Kong.

- Announced a package of measures to ensure that British organisations are neither complicit in nor profiting from the extensive human rights violations in Xinjiang, as part of our efforts to tackle modern slavery.

- Launched our tackling child sexual abuse strategy to drive action in the UK and internationally to disrupt and prevent offending, both online and offline.

- Supported vulnerable children’s education by funding the salaries of over 5,500 teachers in refugee camps in 10 countries through UNHCR. We have also adapted our bilateral programmes in response to COVID-19 to support girls who are hard to reach and at risk of leaving education permanently.

- Launched the Call to Action to Prevent Famine in September 2020 and appointed the UK’s first Special Envoy for Famine Prevention and Humanitarian Affairs. We have since pledged £180 million to tackle food insecurity and famine risk, providing aid to more than seven million vulnerable people in some of the world’s most dangerous places.

We have also pursued measures to enhance our long-term prosperity. For example:

- In under two years, we have secured trade agreements with 66 non-EU countries in addition to our Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU. We have also applied for accession to the CPTPP.

- We have published the 2025 UK border strategy, with the goal of creating a border that is efficient, smart and responsive.

- We have introduced a new points-based immigration system, including a new Global Talent Visa, to attract the best and brightest from around the world. This will ensure we can secure the talent we need for key sectors in our economy, treating EU and non-EU citizens equally.

- We have published a national research and development (R&D) roadmap. Learning from the successes of the Vaccines Taskforce, we have announced an independent Advanced Research and Invention Agency, which will be led by scientists with the freedom to identify and fund transformational science and technology at speed.

In 2021, we will build on this work by convening the G7 and hosting COP26 in partnership with Italy and the Global Partnership for Education with Kenya. Our most immediate priority will be to build back better from COVID-19, demonstrating the benefits of international cooperation. In addition, we will pursue an extensive multilateral agenda on climate change, global health, free and fair trade and economic resilience. We will continue to work with others to reform and strengthen the institutions that support those objectives, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Trade Organization (WTO).

The Government’s long-term approach to 2030

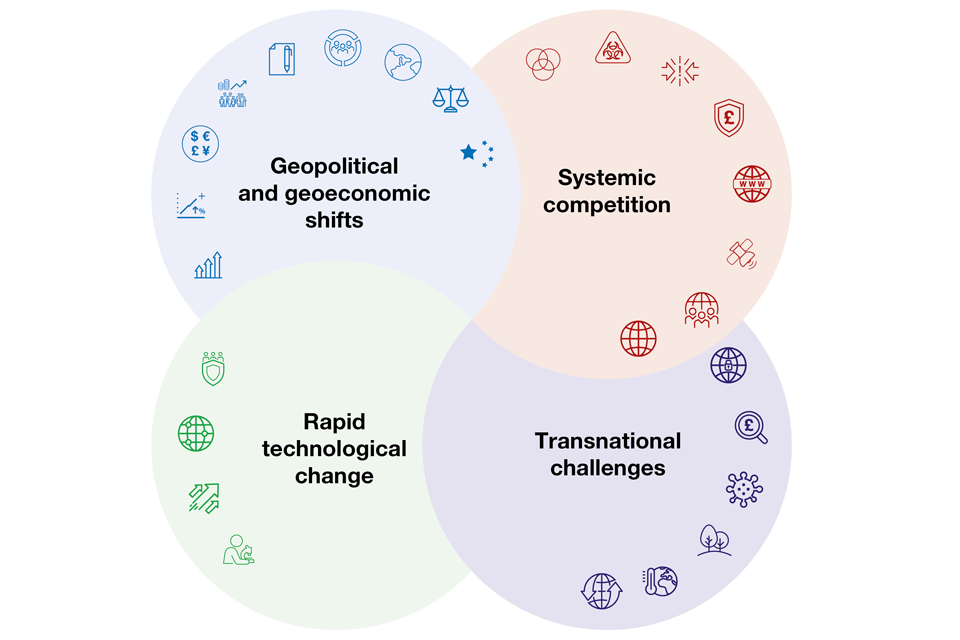

To meet the Prime Minister’s vision for 2030, we will need a long-term strategic approach – combining all the instruments available to government – that continues to adapt to a changing international environment. This is a context defined by: geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts, such as China’s increasing international assertiveness and the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific; systemic competition, including between states, and between democratic and authoritarian values and systems of government; rapid technological change; and transnational challenges, such as climate change, biosecurity risks, terrorism and SOC.

Against this uncertain backdrop, the unifying purpose of the UK’s national security and international policy is to ensure that the things that define us as a nation – our open society and economy founded on democratic values – remain sources of strength and comparative advantage, driving prosperity and improving the well-being of people across the Union.

In the more contested environment of the 2020s, this requires us to be more active in creating a world in which open societies and economies can flourish, shaping the open international order of the future – championing free trade and global cooperation, tackling conflict and instability, and standing up for democracy and human rights. We must also strengthen our security and resilience against those who seek to coerce us, and make it harder for terrorists and organised crime groups to achieve their goals.

The ability to move swiftly and with greater agility, amplifying our strong, independent voice by working with others, will be the determining characteristic of the UK’s foreign policy following our departure from the EU. Our effectiveness will also depend on our ability to maintain a consistent level of international influence, maintaining the soft and hard power capabilities required to support this. We must be prepared to compete with others, and to find new ways to cooperate through creative diplomacy and multilateralism.

In the years ahead we will need to manage inevitable tensions and trade-offs: between our openness and the need to safeguard our people, economy and way of life through measures that increase our security and resilience; between competing and cooperating with other states, sometimes at the same time; and between our short-term commercial interests and our values. Maintaining a long-term perspective will help us navigate the path ahead. Preserving our freedom of action will also enable us to adapt to circumstances as they change.

Introducing our Strategic Framework to 2025

As the outcome of the Integrated Review, we have established a Strategic Framework, which responds to prevailing trends in the international context and is intended to provide handrails for future policy-making to deliver our long-term approach. The Framework sets the Government’s overarching national security and international policy objectives to 2025. It identifies how we can bring all the instruments available to the Government together to achieve these objectives. It does not provide detailed regional and country strategies or an exhaustive description of all the activity we will undertake in the coming years. Instead, it sets a foreign policy baseline and identifies priority actions, reflecting the need for flexibility in our approach and setting out where further policy work and new sub-strategies are required.

The Strategic Framework has been used to guide spending decisions under SR 2020, including departmental settlements and funding for several new initiatives (see Annex A). Future SRs will also be informed by this Framework and will provide further opportunities to align resources with ambition.

The four overarching and mutually supporting objectives set by the Strategic Framework are:

- Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology: we will incorporate S&T as an integral element of our national security and international policy, fortifying the position of the UK as a global S&T and responsible cyber power. This will be essential in gaining economic, political and security advantages in the coming decade and in shaping international norms in collaboration with allies and partners. It will also drive prosperity at home and progress towards the three objectives that follow.

- Shaping the open international order of the future: we will use our convening power and work with partners to reinvigorate the international system. In doing so, we will ensure that it is one in which open societies and open economies can flourish as we move further into the digital age – creating a world that is more favourable to democracies and the defence of universal values. We will seek to reinforce and renew existing pillars of the international order – such as the UN and the global trading system – and to establish norms in the future frontiers of cyberspace, emerging technology, data and space.

- Strengthening security and defence at home and overseas: we will work with allies and partners to address challenges to our security in the physical world and online. NATO will remain the foundation of collective security in our home region of the Euro-Atlantic, where Russia remains the most acute threat to our security. We will also place greater emphasis on building our capacity and that of like-minded nations around the world in responding to a growing range of transnational state threats[footnote 1], radicalisation and terrorism, SOC and weapons proliferation.

- Building resilience at home and overseas: we will place greater emphasis on resilience, recognising that it is not possible to predict or prevent every risk to our security and prosperity – whether natural hazards such as extreme weather events or threats such as cyber-attacks. We will improve our own ability to anticipate, prevent, prepare for, respond to and recover from risks – as well as that of our allies and partners, recognising the closely interconnected nature of our world. And we will prioritise efforts to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss - long-term challenges that if left unchecked threaten the future of humanity - in addition to building global health resilience.

The UK will not be able to achieve these objectives working alone: collective action and co-creation with our allies and partners will be vitally important in the decade ahead – leading by example where we have unique or significant strengths (such as in areas of medical science, green technologies and aspects of data and AI) and identifying where we are better placed to support others in leading the advance towards our shared goals.

The Government will need to combine a planned strategy – which sets long-term objectives, anticipates challenges along the way, and charts a course towards them – with an adaptive approach. Essential to this is deeper integration across government, building on the Fusion Doctrine introduced in the 2018 National Security Capability Review. A more integrated approach supports faster decision-making, more effective policy-making and more coherent implementation by bringing together defence, diplomacy, development, intelligence and security, trade and aspects of domestic policy in pursuit of cross-government, national objectives.

The logic of integration is to make more of finite resources within a more competitive world in which speed of adaption can provide decisive advantage. It is a response to the fact that adversaries and competitors are already acting in a more integrated way – fusing military and civilian technology and increasingly blurring the boundaries between war and peace, prosperity and security, trade and development, and domestic and foreign policy. It also recognises the fact that the distinction between economic and national security is increasingly redundant.

We are already taking major steps towards greater integration across government, including:

-

The creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), bringing our diplomatic and development expertise and policy together, as One HMG overseas.

-

The Integrated Operating Concept 2025, which will deepen integration of UK defence across the five operational domains and with other instruments of state power, and improve interoperability with allies.

-

New cross-cutting capabilities such as the Situation Centre, Counter Terrorism Operations Centre (CTOC), National Cyber Force (NCF) and a national capability in digital twinning.

Finally, the UK will also bring an integrated approach to working with others around the world – that is, we will combine hard and soft power, harness the public and private sector, and deploy British expertise from inside and outside government in pursuit of national objectives.

The principal continuities and changes in our approach

Our Strategic Framework involves significant continuities from the UK’s previous national security and international policy, adapted or upgraded to meet the opportunities and challenges of the coming decade:

- The United States will remain our most important bilateral relationship, essential to key alliances and groups such as NATO and the Five Eyes, and our largest bilateral trading partner and inward investor. We will reinforce our cooperation in traditional policy areas such as security and intelligence and seek to bolster it in areas where together we can have greater impact, such as in tackling illicit finance.

- Collective security through NATO: the UK will remain the leading European Ally in NATO, working with Allies to deter nuclear, conventional and hybrid threats to our security, particularly from Russia. We will continue to exceed the NATO guideline of spending 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) on defence, and to declare our nuclear and offensive cyber capabilities to Allies’ defence under our Article 5 commitment.

- CT and SOC: we will keep our citizens safe from terrorism, working at home and overseas to detect, disrupt and deter terrorist threats, and to address their underlying drivers. Our CT capabilities will be integrated in our new Counter Terrorism Operations Centre. We will also tackle SOC, strengthening the National Crime Agency and regional and local policing, and sustaining our international networks so that we are able to address the links between criminality from the local to international levels.

- Upholding universal human rights: we will continue to act as a force for good in standing up for human rights around the world, providing support to open societies and using our independent (‘Magnitsky-style’) sanctions regime to hold to account those involved in serious human rights violations and abuses.

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): we will remain a world-leading international development donor, committed to the global fight against poverty and to achieving the UN SDGs by 2030. We will support others to become more self-sufficient through trade and economic growth and increase our ability to achieve long-term change through combining our diplomatic and development expertise.

- Girls’ education: we will continue our efforts to ensure all girls have at least 12 years of quality education, using our aid spending and presidency - with Kenya - of the Global Partnership for Education summit in 2021 to make progress towards the global commitment to get 40 million more girls in developing countries into education by 2025.

- An open and innovative digital economy: we will establish the UK as a global services, digital and data hub. And the UK will remain one of the world’s most open economies, championing free and fair trade, welcoming inward investment under our plan for growth, and tackling illicit finance. We will use all our economic tools and our independent trade policy to create economic growth that is distributed more equitably across the UK and to diversify our supply chains in critical goods. Our new Investment Security Unit will safeguard British intellectual property and companies against national security risks, intervening in inward investment where necessary and proportionate.

Attaining our objectives under the Strategic Framework will also involve some significant changes and shifts in policy:

- Shaping the international order of the future: we will move from defending the status quo within the post-Cold War international system to dynamically shaping the post-COVID order, extending it in the future frontiers of cyberspace and space, and protecting democratic values. This will require active diplomacy, especially in using regulatory diplomacy to influence the rules, norms and standards governing technology and the digital economy; it will also require us to maximise our convening power and to do more to win elections for senior positions within multilateral institutions.

- Europe: the UK will remain deeply invested in the security and prosperity of Europe. Our exit from the EU means we have the opportunity to follow different economic and political paths where this is in our interests, and to mark a distinctive approach to foreign policy. Equally, we will work with the EU where our interests coincide - for example, in supporting the stability and security of our continent and in cooperating on climate action and biodiversity.

- Climate and biodiversity: we will lead sustained international action to accelerate progress towards net zero emissions by 2050 and build global climate resilience, starting with our presidency of COP26 in 2021 and our ICF commitment of £11.6 billion. And we will lead efforts to reset the world’s relationship with nature, including by committing £3 billion of our ICF to solutions that protect and restore nature.

- Science and technology: we will take a more active approach to building and sustaining strategic advantage through S&T in support of our national goals. We will create the enabling environment for a thriving S&T ecosystem in the UK and extend our international collaboration, ensuring that the UK’s successful research base translates into influence over the critical and emerging technologies that are central to geopolitical competition and our future prosperity. We will adopt an own-collaborate-access framework to guide government activity in priority areas of S&T, such as AI, quantum technologies and engineering biology.

- Responsible, democratic cyber power: we will adopt a comprehensive cyber strategy to maintain the UK’s competitive edge in this rapidly evolving domain. We will build a resilient and prosperous digital UK, and make much more integrated, creative and routine use of the UK’s full spectrum of levers - including the National Cyber Force’s offensive cyber tools - to detect, disrupt and deter our adversaries.

- Space: we will make the UK a meaningful actor in space, with an integrated space strategy which brings together military and civil space policy for the first time. We will support the growth of the UK commercial space sector, and ensure the UK has the capabilities to protect and defend our interests in a more congested and contested space domain - including through the new Space Command and the ability to launch British satellites from the UK by 2022.

- Indo-Pacific: we will pursue deeper engagement in the Indo-Pacific in support of shared prosperity and regional stability, with stronger diplomatic and trading ties. This approach recognises the importance of powers in the region such as China, India and Japan, and extends to others including South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines. We will seek closer relations through existing institutions such as ASEAN and seek accession to the CPTPP.

- China: we will do more to adapt to China’s growing impact on many aspects of our lives as it becomes more powerful in the world. We will invest in enhanced China-facing capabilities, through which we will develop a better understanding of China and its people, improving our ability to respond to the systemic challenge that China poses to our security, prosperity and values - and those of our allies and partners. We will continue to pursue a positive trade and investment relationship with China, while ensuring our national security and values are protected. We will also cooperate with China in tackling transnational challenges such as climate change.

- Global health: we will work to strengthen global health security, including international pandemic preparedness, through the Prime Minister’s five-point plan. We will seek reform of the WHO, increasing our funding by 30% to £340 million over the next four years, and we will prioritise supporting health systems and access to new health technologies using our Official Development Assistance (ODA).

- Armed forces: we will create armed forces that are both prepared for warfighting and more persistently engaged worldwide through forward deployment, training, capacity-building and education. They will have full-spectrum capabilities, embracing the newer domains of cyberspace and space and developing high-tech capabilities in other domains, such as the Future Combat Air System. They will also be able to keep pace with changing threats posed by adversaries, with greater investment in rapid technology development and adoption.

- State threats: we will bolster our efforts to detect, deter and respond to state threats, to protect our people, infrastructure, economy and values from those who seek to do them harm. We will introduce new legislation to give our security and intelligence agencies and police the powers they need to tackle the challenges we will face in the coming decade.

- Domestic and international resilience: we will improve our ability – and that of our allies and partners – to anticipate, prevent, prepare for, respond to and recover from risks to our security and prosperity. It will be essential to take a whole-of-society approach to resilience across the Union, in addition to cooperating with international partners to address challenges such as climate change and global health risks. Learning from COVID-19, we will improve our ability to anticipate and respond to crises by establishing a cross-government Situation Centre in the Cabinet Office and developing a national capability in digital twinning.

The national security and international environment to 2030

This section describes the Government’s assessment of the strategic context to 2030. Its judgements are drawn from the evidence base assembled during the Integrated Review (see Annex B), including external consultation, the public call for evidence and internal analysis.

The nature and distribution of global power is changing as we move towards a more competitive and multipolar world. Over the coming decade, we judge that four overarching trends will be of particular importance to the UK and the changing international order:

- Geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts: such as China’s increasing power and assertiveness internationally, the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific to global prosperity and security, and the emergence of new markets and growth of the global middle class.

- Systemic competition: the intensification of competition between states and with non-state actors, manifested in: a growing contest over international rules and norms; the formation of competing geopolitical and economic blocs of influence and values that cut across our security, economy and the institutions that underpin our way of life; the deliberate targeting of the vulnerabilities within democratic systems by authoritarian states and malign actors; and the testing of the boundary between war and peace, as states use a growing range of instruments to undermine and coerce others.

- Rapid technological change: technological developments and digitisation will reshape our societies, economies and change relationships – both between states, and between the citizen, the private sector and the state. S&T will bring enormous benefits but will also be an arena of intensifying systemic competition.

- Transnational challenges: such as climate change, global health risks, illicit finance, SOC and terrorism. These threaten our shared security and prosperity, requiring collective action and multilateral cooperation to address them. Of these transnational challenges, climate change and biodiversity loss present the most severe tests to global resilience and will require particularly urgent action.

These trends will overlap and interact, and the long-term effects of COVID-19 will influence their trajectory in ways that are currently difficult to predict.

The realistic optimum scenario is an international order in which these trends can be managed effectively, with nations coming together to revive multilateral cooperation, strengthen global governance and harness the opportunities ahead for growth and prosperity. We must also prepare for the possibility that the post-COVID international order will be increasingly contested and fragmented, reducing global cooperation and making it harder to protect our interests and values. The Strategic Framework that follows this chapter is designed to help us navigate the challenges ahead, laying out how we will work with others, maximising opportunities and minimising risks to the UK

Venn diagram of the four main global trends to 2030 as highlighted in the Integrated Review: geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts; systemic competition; rapid technological change; transnational challenges. In each circle there are icons representing the different themes that come under each trend.

Geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts: moving towards a multipolar world

There will be significant areas of geopolitical and geoeconomic continuity in the 2020s: the US will remain an economic, military and diplomatic superpower, and the UK’s most important strategic ally. The Euro-Atlantic region will remain critical to the UK’s security and prosperity; partnerships beyond the immediate European neighbourhood will also remain important. Russia will remain the most acute direct threat to the UK, and the US will continue to ask more from its allies in Europe in sharing the burden of collective security.

Overall, however, the distribution of global political and economic power – both within and between states, and between regions – will continue to change, with direct and indirect implications for UK interests. By 2030, it is likely that the world will have moved further towards multipolarity, with the geopolitical and economic centre of gravity moving eastward towards the Indo-Pacific.

China as a systemic competitor. China’s increasing power and international assertiveness is likely to be the most significant geopolitical factor of the 2020s. The scale and reach of China’s economy, size of its population, technological advancement and increasing ambition to project its influence on the global stage, for example through the Belt and Road Initiative, will have profound implications worldwide. Open, trading economies like the UK will need to engage with China and remain open to Chinese trade and investment, but they must also protect themselves against practices that have an adverse effect on prosperity and security. Cooperation with China will also be vital in tackling transnational challenges, particularly climate change and biodiversity loss.

Shifts in the global balance of economic power. Drivers of growth in the global economy are likely to continue moving to the south and east, in particular towards the Indo-Pacific region. The rapid growth of emerging markets is also expected to increase the size of the global middle class, from 3.8 billion people in 2018 to 5.3 billion in 2030, increasing opportunities for trade in higher value-added goods and services. This will offer considerable opportunity for countries like the UK with strengths in these areas.

Global growth and economic stability. Before COVID-19, the world was already facing a decade of weak growth. COVID-19 has caused a deep global recession and the economic impact of the pandemic is likely to dominate the first half of the decade, with the shape of the recovery uncertain. Further economic shocks are possible, for example caused by the uneven impact of new technologies across and within states. The expected shift away from fossil fuels is likely to present economic challenges, particularly for oil-producing countries.

Challenges to an open global economy. Globalisation began to stall after the 2008-09 financial crisis. COVID-19 will likely accelerate the trend towards more regional and national approaches, although trade flows recovered relatively quickly following the initial shock. The momentum for trade liberalisation may continue to slow and cases of protectionism increase, driven by political and economic conditions within states and the increasingly aggressive use of economic and trade policy as a lever in competition between states.

Decreasing global poverty. Global poverty has reduced markedly in recent decades, and is projected to fall to under 5% by 2050. After the immediate shock of COVID-19, the momentum towards poverty reduction is likely to resume, with absolute poverty estimated to be almost eliminated in Asia and Latin America in the 2030s. Under current trends, however, Africa will increasingly be left behind: by 2045, it is likely that around 85% of the poorest billion people will live in Africa.

Improvements in global education. Over the coming decades, technology is likely to significantly improve access to and the quality of education globally. By 2050, almost anyone is likely to have easy access to online education, with technology becoming increasingly portable, accessible and high-speed. This is likely to help sustain improvements in global literacy rates. In 2000, 81% of the world’s population was able to read; by 2016 this had increased to 86% and by 2050 it is likely to be around 95%.

Changing demographics. The global population is expected to reach 8.6 billion by 2030. Population growth will be greatest in sub-Saharan Africa, interacting with other trends, including climate change, poverty and conflict and instability. Globally, demographic imbalances will become more pronounced, with ageing populations in more parts of the world.

Geopolitical importance of middle powers. Increasing great power competition is unlikely to mean a return to Cold War-style blocs. Instead, the influence of middle powers is likely to grow in the 2020s, particularly when they act together. In this context, the Indo-Pacific will be of increasing geopolitical and economic importance, with multiple regional powers with significant weight and influence, both alone and together. Competition will play out there in regional militarisation, maritime tensions, and a contest over the rules and norms linked to trade and technology.

Challenges to democratic governance. The geopolitical role of non-state actors, in particular large tech companies, is likely to continue to grow. In some democracies, inequality – made more visible by digital technology – may increase social and political dissatisfaction. Governments may struggle to satisfy popular demands for security and prosperity, with trust further undermined through disinformation. Authoritarian states will face and confront similar challenges with a different toolkit, including the use of technologies for surveillance and political control.

Systemic competition: a more contested international environment

In a multipolar world, there will be a growing contest between states and groups of states to shape the international environment. Non-state actors – ranging from large tech companies to organised crime groups – will participate in this competition, increasing its complexity.

Systemic competition will determine the shape of the future international order: the extent to which it is open, upholding the free exchange of ideas and trade, and facilitating cooperation on transnational challenges; or fragmented and broadly divided into geopolitical neighbourhoods and technological ecosystems, eroding cooperation between nations and enabling the spread of authoritarianism. Competition is likely to be ‘systemic’ in a number of ways:

Competition between political systems. Ideological competition between different types of political system will increase. On current trends, the 15-year decline in democracy and pluralism will continue to 2030, accelerated by COVID-19. Tensions between democratic and authoritarian states are highly likely to become more pronounced, as authoritarian states seek to export their domestic models, undermine open societies and economies, and shape global governance in line with their values.

Competition to shape the international order. Competition will increase the strains on the existing multilateral architecture, weakening established rules and norms that govern international conduct. In some areas, such as emerging technology or space, there will be a growing contest - in which non-state actors will play an important role - to shape new rules, norms and standards, and to control access to shared resources such as space. Those parts of the international architecture where multilateral cooperation adds value, such as the International Financial Institutions, are more likely to thrive. Conversely, where multilateral approaches are blocked, nations will likely caucus in smaller, regional or like-minded groups.

Competition across multiple spheres. Competition will continue within the conventional military domains of land, sea and air, and will grow in other spheres, including technology, cyberspace and space, further shaping the wider geopolitical environment. Systemic competition will further test the line between peace and war, as malign actors use a wider range of tools - such as economic statecraft, cyber-attacks, disinformation and proxies - to achieve their objectives without open confrontation or conflict. The UK is likely to remain a priority target for such threats. Our ability to deter aggression will be challenged by new techniques and technologies.

A deteriorating security environment. Proliferation of CBRN weapons, advanced conventional weapons and novel military technologies will increase the risk and intensity of conflict and pose significant challenges to strategic stability. The advantages offered by high-tech capabilities may be eroded by affordable, easily-available, low-tech threats such as drones and improvised explosive devices. Opportunistic states will increasingly seek strategic advantage through exploiting and undermining democratic systems and open economies. Russia will be more active around the wider European neighbourhood, and Iran and North Korea will continue to destabilise their regions. The significant impact of China’s military modernisation and growing international assertiveness within the Indo-Pacific region and beyond will pose an increasing risk to UK interests.

Growing conflict and instability. The last decade saw an increase in violent conflict globally. 2016 and 2019 witnessed the highest number of active armed conflicts internationally since 1946 - the majority being civil wars involving external actors. To 2030, conflict and instability will remain prevalent and may increase unless concerted action is taken to address underlying political, social, economic and environmental drivers, especially in fragile states. Driven by systemic competition, external powers will likely remain involved in national and regional conflicts, influencing their course in pursuit of their own advantage. This will increase the risk of conflicts escalating.

Economic statecraft. More states will adopt economic statecraft as a lever in systemic competition. As well as greater protectionism and economic nationalism, this will sometimes include the deliberate use of economic tools – from conventional economic policy to illicit finance – to target and undermine the economic and security interests of rivals. There will be increased competition for scarce natural resources, such as critical minerals including rare earth elements, and control of supply may be used as leverage on other issues.

Cyberspace. Cyberspace will be an increasingly contested domain, used by state and non-state actors. Proliferation of cyber capability to countries and organised crime groups, along with the growing everyday reliance on digital infrastructure, will increase the risks of direct and collateral damage to the UK. Consequently, cyber power will become increasingly important. There will be a struggle to shape the global digital environment between ‘digital freedom’ and ‘digital authoritarianism’, which will have significant implications for real-world governance.

Space. Space will be a domain of increasing opportunity, as the application of new technologies in space enables new possibilities – from commercial opportunities to international development and climate action. But increasing commercial and military use of space will make it an important sphere of competition; there will be considerable risks to strategic stability if this is not managed and regulated effectively.

Rapid technological change: science and technology as a metric of power

S&T will be of central importance to the strategic context: critical to the functioning of economies and societies, reshaping political systems and a source of both cooperation and competition between states. This will unfold in a number of ways:

A rapidly changing landscape. The S&T landscape has changed significantly since 2015 and the pace of change will accelerate further to 2030. Novel technologies and applications are being developed and adopted faster than ever before. AI is accelerating scientific discovery; quantum technologies are expected to bring advances in medical imaging and in measuring electric, magnetic and gravitational fields; and advances in clean technologies will equip us with new and cheaper tools to tackle climate change. New analytical techniques are producing greater insight from increasing volumes of data, enabling innovation.

S&T as an arena of systemic competition. Over the coming decade, the ability to advance and exploit S&T will be an increasingly important metric of global power, conferring economic, political and military advantages. The tech ‘superpowers’ are investing to maintain their lead. At the same time, many more countries are now able to compete in S&T, while large technology companies are able to grow more powerful by absorbing innovations produced by small companies. Competition is therefore intensifying, shaped in particular by multinational firms with the backing of states, some of which take a ‘whole-of-economy’ approach to ensure dominance in critical areas. Maintaining competitive edge will rely on preeminence in and access to technology - as well as access to the human and natural resources needed to harness it - and the ability to protect intellectual property. As the volume of data grows exponentially, the ability to generate and use it to drive innovation will be a crucial enabler of strategic advantage through S&T.

New challenges to security, society and individual rights. Technology will create new vulnerabilities to hostile activity and attack in domains such as cyberspace and space, notably including the spread of disinformation online. It will undermine social cohesion, community and national identity as individuals spend more time in a virtual world and as automation reshapes the labour market. While the exploitation of personal data will support the growth of innovation, it will also pose challenges to individual privacy and liberty, including through the increased availability of surveillance technologies.

Technology and data standards. Technological advances have always driven global rule-making. But in the years ahead, the enormous pace of change is likely to result in a growing gap between what technological advances make possible and the limits of existing global governance. This will make frontier spaces - and the technologies, infrastructure and data underpinning their use - subject to intense competition over the development of rules, norms and standards.

Transnational challenges: tests of resilience and international cooperation

COVID-19 will not be the only global crisis of the 2020s. The world faces transnational challenges which overlap, reinforce each other and require a global response. This will include, for example: climate change and biodiversity loss driving poverty, instability and migration; states continuing to use organised crime groups as proxies in systemic competition; and technology both facilitating and helping to detect terrorism, SOC and illicit finance.

Climate change. Global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry increased from five billion tonnes to more than 36 billion between 1950 and 2019. Significant action to decarbonise the global economy is needed by 2030 to prevent climate change from accelerating rapidly and possibly irreversibly: under current policies the world is heading for around 3.5 degrees of warming by the end of the century, with real risks of even higher warming. Economic recovery from COVID-19 offers a chance to accelerate the transition to net zero. At the same time, the impact of existing climate change will cause increasing damage: more frequent and intense events such as extreme heat, storms and rain, leading to increased flooding, landslides and other impacts such as wildfires. This can amplify displacement and migration - increasing food and water insecurity - and damage ecosystems. The effects will be felt most acutely in sub-Saharan Africa, South and East Asia and the Middle East, with a disproportionate impact on areas that are already fragile and on the people who live in them.

Biodiversity loss. Global biodiversity is already in unprecedented decline: 75% of the world’s land surface and 66% of the ocean has been significantly altered and degraded by human activity and an estimated one million species are threatened with extinction. To 2030, unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, population growth and technological developments will cause further biodiversity loss, as a result of land and sea use change, overexploitation, climate change, pollution and invasive alien species. This will have particularly severe consequences for the world’s poor and vulnerable.

Global health. Infectious disease outbreaks are likely to be more frequent to 2030. Many will be zoonoses – diseases caused by viruses, bacteria or parasites that spread from animals to humans – as population growth drives the intensification of agriculture and as the loss of habitats increases interaction between humans and animals. Another novel pandemic remains a realistic possibility. On current trends, global deaths related to antimicrobial resistance will rise from 700,000 to 10 million per year by 2050.

Migratory flows. Migration will remain a permanent feature of the global landscape. Demographic change, climate change, biodiversity loss, conflict and instability and poverty – exacerbated by the effects of COVID-19 – will drive increased population movements, with Europe the destination for mass migration from the Middle East and Africa in particular. But interstate and intrastate migration is likely to have more stressful effects in other parts of the world.

Radicalisation and terrorism. Terrorism will remain a major threat over the coming decade, with a more diverse range of material and political causes, new sources of radicalisation and evolving tactics. In the UK, the main sources of terrorist threat are from Islamist and Northern Ireland-related terrorism, and far-right, far-left, anarchist and single-issue terrorism. In Northern Ireland, there remains a risk that some groups could seek to encourage and exploit political instability. Overseas, poor governance and disorder, particularly in Africa and the Middle East, is likely to increase space for terrorist and extremist groups to operate. There is a realistic possibility that state sponsorship of terrorism and the use of proxies will increase. It is likely that a terrorist group will launch a successful CBRN attack by 2030.

Serious and organised crime and illicit finance. SOC will continue to have a significant impact on UK citizens. The scale and complexity of SOC will likely increase – aided by new technologies – and will adapt to events faster than governments. Most SOC will continue to be transnational: criminals will source illicit goods, exploit the vulnerable and defraud UK citizens and businesses from overseas. SOC will also enable threats such as state threats and terrorism, and will undermine regional stability, especially in post-conflict zones. It will continue to be facilitated by cross-border flows of illicit finance, with tens of billions of pounds likely to be laundered through the UK every year.

Strategic Framework

Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology

The rapid pace of change in science and technology (S&T) is transforming many aspects of our lives, fundamentally reshaping our economy and our society, and unlocking previously inconceivable improvements in global health, well-being and prosperity. As competition grows between states, S&T will also increase in importance as an arena of systemic competition. In the years ahead, countries which establish a leading role in critical and emerging technologies will be at the forefront of global leadership.

The UK has a strong record of innovation in S&T - discovering graphene, decoding the structure of DNA, and contributing life-saving treatments and a vaccine to the global effort against COVID-19. In the fast-evolving and more contested environment ahead, the UK must take an active approach to building and sustaining a durable competitive edge in S&T - anticipating, assessing and taking action on our S&T priorities to deliver strategic advantage for the UK. This will become increasingly important to our domestic prosperity and our international relationships in the coming decade. It is also an essential foundation for all the objectives in this Strategic Framework: ensuring that the UK has the tools and influence to shape a future international order based on democratic values; bolster our security and maintain military advantage; and contribute to building a more resilient world.

Our first goal is to grow the UK’s science and technology power in pursuit of strategic advantage. Achieving this objective requires a whole-of-UK effort, in which the Government’s primary role is to create the enabling environment for a thriving S&T ecosystem of scientists, researchers, inventors and innovators, across academia, the private sector, regulators and standards bodies, working alongside the manufacturing base to take innovations through to markets. It also requires strategic choices and decisions by the Government, both on S&T priorities and on how we use our national S&T capability in support of wider policy goals - from net zero through to economic growth.