January 2022

Introduction

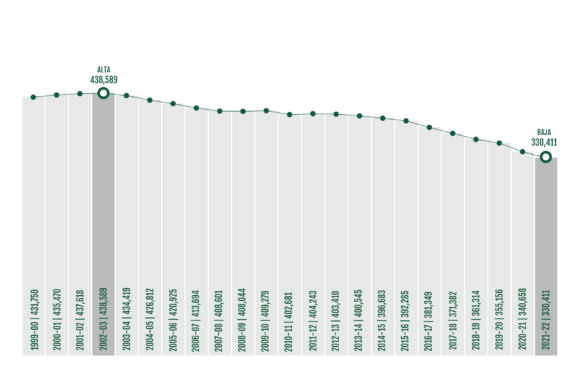

Figure 1. CPS Enrollment (School Years 1999-00 to 2021-22)

Chicago's Enrollment Decline

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the third-largest school district in the nation, has lost more than 100,000 students in the last 20 years. Of that, more than 60,000 left in the last decade, more than 40,000 of those in the past five years alone.

In 2000, CPS enrollment stood at more than 430,000 students. Today, just slightly more than 330,000 students attend CPS — and there is a consistent decline of as many as 10,000 public school students each year.

This report dives deep into these key questions:

- What are the drivers for the enrollment decline in CPS?

- Where have students enrolled outside of CPS schools?

- What does fewer students mean for CPS and Chicago?

- What might be done to stave off further enrollment drops that could cost the district billions in education funding?

Unfortunately, the answers are complicated. A confluence of decreasing births, slowing growth of Latine families in Chicago, and increasing out-migration of Black families away from Chicago contributes to CPS’s accelerating enrollment decline.

Why School Enrollment Matters

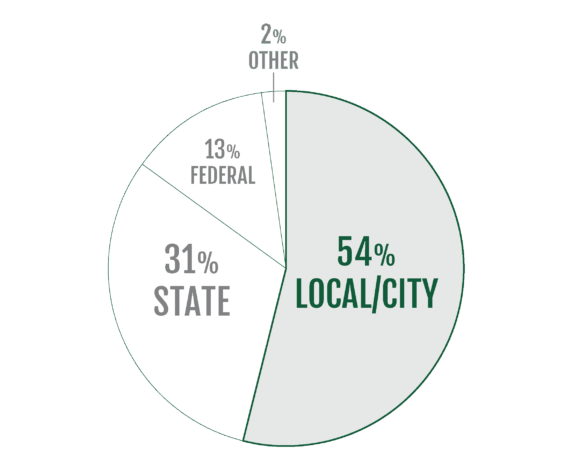

Figure 2. CPS Funding Sources (School Years 1999-00 to 2021-22)

How CPS is Funded

Nearly one-third of CPS’s funding comes from the state of Illinois, which uses an evidence-based funding (EBF) formula. EBF relies heavily on prior-year student enrollment to fund the state’s school districts, including CPS.

Because each year’s budget is based on how many students a school district serves, lower enrollment means less funding for district schools while some costs, like maintaining buildings, remain fixed.

How Low Enrollment Affects Schools Adversely. At CPS, funding for the school year is based on the number of students enrolled in school on the 20th day of the previous school year (often called the “20th-day enrollment count date”).

The number of students enrolled at each school is used to determine the base amount of funds that a school receives for core instruction, a process called Student-Based Budgeting (SBB). Therefore, low-enrolled schools receive fewer dollars and thus often lack the resources needed for their students and educators.

Faced with hundreds of schools experiencing low or declining enrollment, CPS began providing those schools with additional resources to offset the impact of decreased revenue from SBB. For School Year (SY) 2021-22, CPS provided an additional $32 million to 262 schools toward this effort.

While the infusion of $1.8 billion of federal COVID-19 relief funding to CPS will certainly help to soften and subsidize school enrollment-driven budget declines in the short term, these one-time funds are only a temporary stopgap.

Another complicating factor is that CPS, according to the state’s calculations, receives only 66% of the local and state resources needed to meet its students’ needs.

Even if the per-student amount of funding were to stay the same, it would not be enough to provide a high-quality, equitable education for students. Additionally, when there are fewer students, a school’s per-pupil resources cannot extend as far.

Put another way: School leaders are not able to reach an efficient economy of scale within the school, reducing access to necessary student supports.

If CPS’s enrollment trend is not reversed, declining revenue from the state coupled with substantial fixed costs—primarily in personnel and building maintenance—will inevitably force CPS and individual schools to make difficult budgetary decisions in the years ahead. While the district undoubtedly would strive to avoid cuts that impact student learning, it is difficult to fathom a scenario where student outcomes improve and opportunity gaps close while CPS faces annual revenue declines due to lower student enrollment.

Understanding the National Trends

Are There Fewer School-Aged Children?

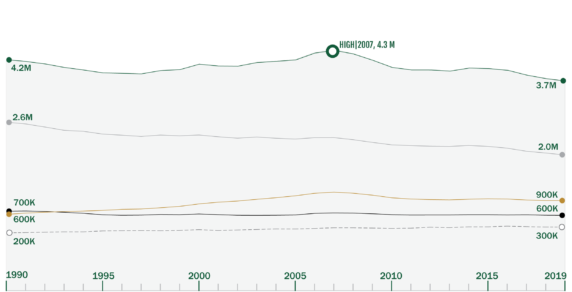

Figure 4. National Births Over Time by Race

What We Learned:

CPS’s enrollment crisis is not a uniquely Chicago problem. Enrollment in urban districts across the country is declining, while there is an upward trend in the proportion of students choosing to attend public schools.

From 2009 to 2019, the U.S. saw a 3% increase in public school enrollment, from 49.4 million to 50.7 million students. This increase was partially driven by a decline in private school enrollment, which fell by 300,000 students from 1999 to 2017.

The increase in public school students from 2010 to 2019 was driven by public schools taking a larger proportion of available school-age children — not by an uptick in the number of children in the population.

The overall number of U.S. children under the age of 18 declined over the course of a decade, from 74 million in 2010 to 73 million by 2019.

Disaggregating by race reveals that populations of children increasing include Latine (+1.5 million), Asian (+440,000), and Other/Multiracial (+500,000). Over the same period, the number of White and Black children declined by 3 million and 400,000, respectively.

The main reason for the decline in the number of school-age children is lower births.

Chicago’s Unique Challenge

4 in 5 Chicago School-Age Children Enroll in CPS

Chicago’s population of school-age children has also declined. While fewer births across all demographic groups are a key driver, other reasons for the decline are more nuanced and complex. Since 1960, the number of children ages 3-18 in the city of Chicago declined by nearly half from 760,000 to 398,000.

Put another way: There is approximately only one child today for every two children in 1960.

Despite the decline in school-age children, CPS remains the top education choice for Chicago families. CPS’s market share — that is, the percentage of school-age children in Chicago who attend CPS schools versus other options such as private, Catholic, and home schools — grew by 20% from 1960 to 2018, from 61% to 81%.

Since 2000, approximately four out of five school-age children in Chicago have enrolled in CPS — despite leadership transitions, labor strife, multiple budget crises, and a global pandemic.

CPS’s data indicates it did not lose a majority of students to non-public schools in Chicago or to homeschooling: Since 2019-20, CPS indicates that nearly 18,000 students transferred out of the city altogether; however, over that same period, only 727 students left the district for non-public schools and only 658 transitioned to homeschooling.

Rather, Chicago’s school-age population decline — and the resulting decline in CPS enrollment — can be attributed to three key drivers:

- Declining births;

- Slowing growth of Latine families; and

- Increasing out-migration of Black families.

Key Driver

01 | Declining Births

Examining the First Key Driver

According to the U.S. Census, from 2010 to 2020, Chicago’s population grew 2% to 2.7 million residents, offsetting a 7% decline that occurred over the previous decade.

While 2.7 million residents is 50,000 more Chicagoans than there were in 2010, the number is 150,000 shy of the population in 2000. Chicago remains the third-largest city in the U.S. and CPS remains the third-largest public school district in the country.

Despite modest population growth over the past decade, Chicago has seen a significant decline in births over that same period, mirroring national trends. From 2009 to 2019, births in Chicago fell from approximately 44,000 children born per year to 33,000 children born per year.

In 2009, approximately 30,000 Kindergarteners enrolled in CPS. By 2021, this number had fallen to less than 22,000. This trend holds across all racial/ethnic groups.

As a result, there are approximately 11,000 fewer students available in Chicago for each successive school year than there were a decade prior.

“... the opportunity to grow student enrollment in places like Chicago relies heavily on retaining the population we have and attracting non-residents to move to our city”

— Chicago's Enrollment Crisis, Part One, Kids First Chicago, January 2022

Key Driver

02 | Slowing Growth of Latine Families

Understanding the National & Local Latine Population

America’s Latinx/a/o population played a significant role in driving U.S. population growth over the past decade, though the group is not growing as quickly as it once did.

From 2010 to 2019, the U.S. population increased by 18.9 million, and Latinx/a/o residents accounted for more than half (52%) of that growth.

In 2019, the Latine population reached a record 60.6 million, making up 18% of the U.S. population — an increase of 10 million people and two percentage points from the decade prior. However, the country’s Latine population is growing more slowly than it did previously, due to a decline in the annual number of births and a drop in in-migration.

From 2015 to 2019, the Latine population grew by an average of 1.9% per year, down significantly from a peak of 4.8% from 1995 to 2000.

This trend is reflected in cities and counties across the country, including Chicago. Specifically, three factors contribute to slower growth from Chicago’s Latine population:

- Declining birth rates;

- Declining in-migration from Latin America, particularly from Mexico; and

- Increasing gentrification

-66%

America's Latine Population Growth Declined by Approximately 66% from 2015 to 2019 in Comparison to 1995 to 2000

-22%

Student Enrollment in the Pilsen/Little Village Decline by 22% Over the Last 5 Years, Demonstrated by Chicago Public Schools' Annual Regional Analysis

Key Driver

03 | Increasing Out-Migration of Black Families

"...For every 10 school-age black children who leave the city, 8 of them are likely to have been CPS students."

A Black Exodus

In addition to slower growth within Chicago’s Latine population, the third reason for the decline in the city’s population has been the continued out-migration of Black families—a large-scale Black exodus.

There were 85,000 fewer Black residents in Chicago in 2020 compared to 10 years prior when the Black population was the largest racial group in the city.

Since 2000, Chicago has lost more than 260,000 Black residents. The Black population is the lowest it has been since the 1960 census and is now the third-largest population group in the city. Whereas other population groups have seen declines based primarily on total births, the decline in Black residents is being driven by a mass departure of these families from the city.

As an example, Englewood, one of Chicago’s 77 community areas, boasted nearly 100,000 people in 1960 but is now home to about 22,000.

These local population shifts are critical as we consider the future of public schools in Chicago. As noted, CPS currently enrolls more than 80% of all school-age children in the city. However, different demographic populations enroll in public schools to varying degrees.

As of 2018, more than 85% of Black and Latine children are enrolled in public schools in Chicago, on par with the 80% of Asian families who choose CPS. However, only 55% of Chicago’s White school-age children are CPS students.

What's driving the black exodus? According to a 2020 report from the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), “Black population trends in Chicago are associated with trends in levels of racial inequality, as indicated by racial disparities in unemployment and wages.”

Chicago was once seen as a mecca for Black opportunity. But, as UIC’s report notes, a variety of factors have led to the exodus, including the demolition of public housing, the closing of public schools, the continuing effects of foreclosures and the housing crisis, the lack of access to health care, the prevalence of food deserts, the substantial wage gaps, and the high unemployment rates. High rates of crime and violence are symptoms of inequities and have also influenced many Black families’ decisions to leave the city. The latest factor is the disproportionate impact of the pandemic felt by Chicago’s Black residents.

Today, we are watching a Great Migration in reverse.

We left Chicago because of the high cost of quality child care. Leaving Chicago, we were able to afford both a house and child care. We couldn't have done both living in the city.

—Emani Johnson, On Moving to the Chicago Suburbs