Chautauqua

2 0. 2

c h a n c e e n c o u n t e r s

2 0. 2

c h a n c e e n c o u n t e r s

E ditor

jill g E rard

a dvisory E ditor

diana hum E g E org E

m anaging E ditor

jam E s king

C ov E r & B ook d E sign

ga B i st E ph E ns

a ssistant E ditors

jana C C arv E r

krist E n dors E y

mari E marrinan

gillian pri B i C ko

E ditorial a ssistants

m E lissa C rip E

B arr E t gi E hl

ra C h E l ni C holson

sydn E y norman

sas C ha siz E mor E

C hautauqua i nstitution a r C hiv E s

jonathan s C hmitz

W ith s p EC ial t hanks to

E mily C arp E nt E r

mi C ha E l ramos

E mily louis E smith

sony ton - aim E

C hautauqua institution

univ E rsity of north C arolina W ilimington ,

d E partm E nt of C r E ativ E W riting

Every conversation is a story, and every story is an adventure, and every adventure takes me out of my small life into a larger one, and I love that. I love that it catapults me out into the world, outdoors, in all seasons, to places I have only dreamed of going—or maybe never dreamed of going—places where they speak in different accents, different languages even. Where the air smells different, and the skyline is unfamiliar, and the landscape is a brand new map.”

—Philip Gerard, “On Fire for Research”Copyright © 2023 Chautauqua Institution

Chautauqua is published each June by Chautauqua Institution, a not-for-profit corporation under section 501(c)(3) of the United States Revenue Code. The opinions expressed in Chautauqua are not necessarily the opinions held by the editors or by Chautauqua Institution.

On the Cover: Guardian, Samantha Wall, Ink on Dura-Lar, 84" x 40"

Below photos courtesy of Chautauqua Institution Archives: At the Ranch, 1899, Robert A. Miller Bell Tower by Night, 1983, Rogers Bicycles at the Girls Clubhouse, August 7, 1969, S.G. Wertz Painting Model, 1945–1955, Lloyd S. Jones

Other Photos:

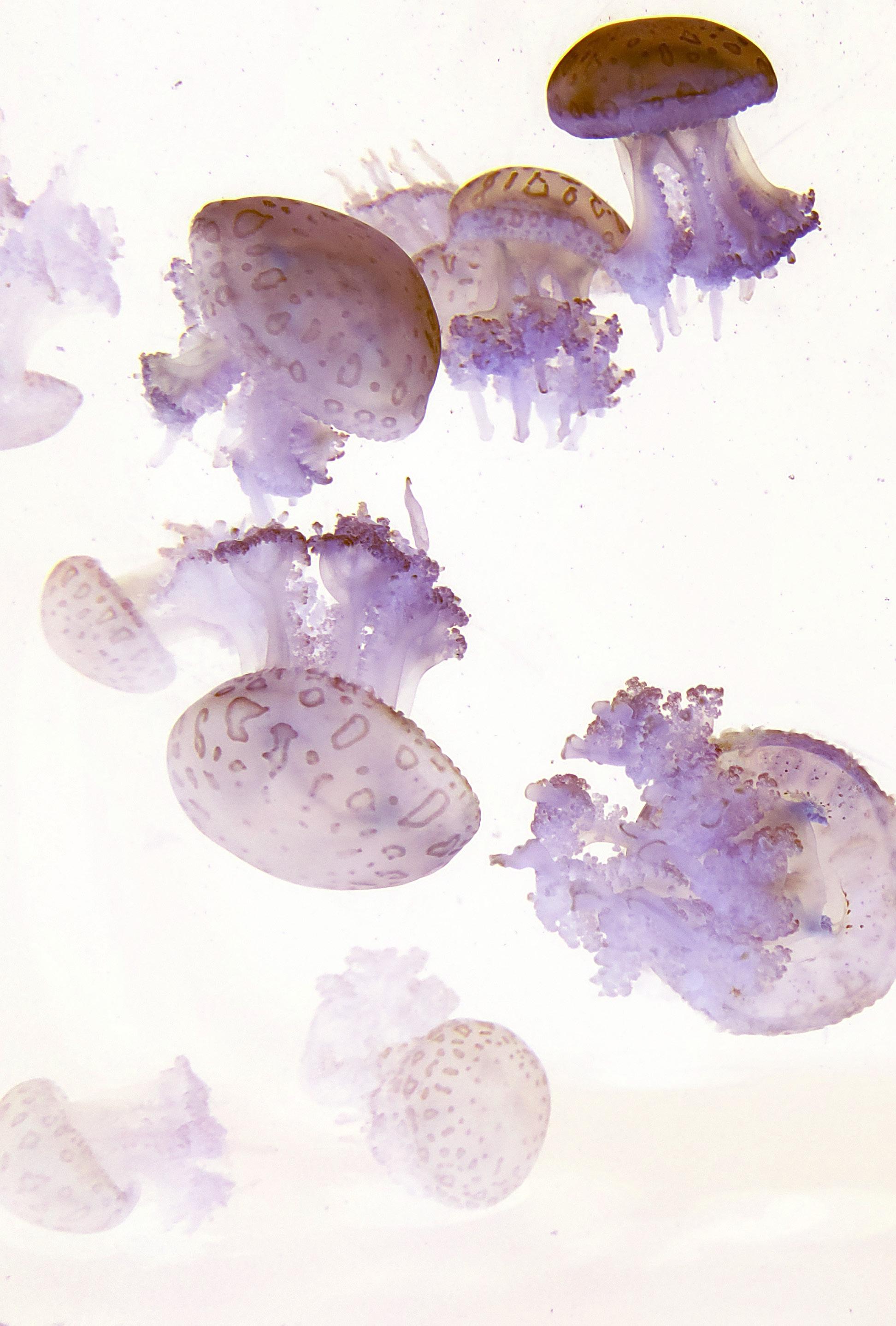

https://unsplash.com/photos/sOBfJjqptIE, January 15, 2020, Justin Campbell Unsplash, 1js7b9_sRJI, Chuttersnap Adobestock_299480836

https://unsplash.com/photos/2HXay3YD5EA, July 19, 2022, Ben Wicks

https://unsplash.com/photos/z9vkyDW9brw, November 18, 2020, Sahand Babali March 2023, Gillian Pribicko

https://unsplash.com/photos/M6-6v-vZhHc, September 19, 2020, Roberto Delfanti Stray Cups, Linda Vasconi

ISSN 1549-7917

Produced by The Publishing Laboratory Department of Creative Writing University of North Carolina Wilmington

601 South College Road

Wilmington, NC 28403-5938

www.uncw.edu / writers

For more than a hundred and thirty years, Chautauqua Institution has served as a stage and a classroom for leading figures of the times, including Ulysses S. Grant, Booker T. Washington, Alexander Graham Bell, Susan B. Anthony, and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The Chautauqua way is a habit of living in a state of continual enrichment: learning on vacation, finding intellectual stimulation in leisure, imbuing all activities with a passion for art. Learning and art should not be confined to separate spaces or designated hours, nor spirituality expressed only within sacred walls or books of prayers.

Chautauqua is a literary manifestation of the values and aesthetics of Chautauqua Institution. Each volume is a portable Chautauqua season between covers. The sections loosely reflect the categories of experience addressed during those nine summer weeks, playing one writer’s vision off another’s in the spirit of oblique, artful dialogue.

The Chautauqua way is also reflected in how we make this book. Each year, in partnership with the Chautauqua Literary Arts, graduate and undergraduate students in the Department of Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington work as members of the editorial team, guided by professional editors and an advisory board. They read and discuss submissions, fact check and edit, search for art, and participate in the artistic process of building a book, to be released at the start of the summer season.

In our editorial sessions, we read aloud excerpts or even entire works, listening for the music of great writing, searching for the piece that eloquently addresses the issue’s theme through some facet of the life in art, spirit, or play, or a life lesson. Writers, ages twelve through eighteen, enjoy that same respectful attention through Young Voices.

So settle back on a couch or a comfortable patch of grass and spread this book open like a tent. Immerse yourself in the world of ideas, imagination, and language that lives between its covers. For as many minutes or hours as you like, you are part of the Chautauqua community.

Jill Gerard, Editor Chautauqua InstitutionGuardian, Samantha Wall Ink on Dura-Lar, 84" x 40"

Theart on this cover, Guardian, was provided by the artist, Samantha Wall. It appeared, alongside other drawings by Wall, in the 2022 Chautauqua Visual Arts exhibition “All that Glitters.” Her work in this exhibition is described as “slippery yet impeccably rendered,” and a reminder “of the complicated importance of human connection.”

Wall’s golden drawings in this exhibition are representative of figures shaped by more than one culture. The metallic quality in each piece is a nod to the Korean celebration of Dol, or a child’s first birthday, during which gold rings are given as gifts to the family in hopes of funding the child’s future endeavors. For Wall, who was born in Korea but has lived most of her life in the United States, the tradition “became a point of entry to explore family history and cultural identity.”

In thinking about the cover art for Chance Encounters, I kept coming back to the importance not only of instances of human connection that shape our lives, but also our encounters with culture, art, tradition and the divine. I was interested in how those experiences allowed for a deepening of connection and understanding between people as well as with oneself. Wall’s drawings in this exhibition are a shining example of how encounters with art, family, and culture can shape a person and their creative practice—the way they show up in the world.

To see more of Wall’s work go to samanthawall.com or find her on instagram as @samanthawall.

Chautauqua thanks Chautauqua Institution and the Department of Education for their support of the journal.

roger hart The Strong Force

john hoppenthaler After Listening to the Weather, I Pull into a Bar

susan polizzotto Tree Frogs or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Hurricanes

tricia bogle Bronx, 1995

geraldine connolly Two Foxes

janice e . rodríguez Miles to Go

chun yu The Pink Balloon

doug ramspeck Six Omens in Six Days

polly brown Parsley Caterpillar / Black Swallowtail

barbara west Satsuma for Cherie

mary gilliland Revealing the Passenger List

elizabeth garcia Japanese Bathtub

whitney hudak Most Beautiful Thing

quincy gray mcmichael Farming After Death

joanne m . clarkson Crossing Midnight

paul pedroza Criterion No. 1: He Took Himself to the Lake

xiaoly li Horn Pond in May

xiaoly li You Need to Be a Good Hunter or a Born Goddess to Get Out of It

ann aspell Intermission

michael quattrone Eastbound on I-80

michael quattrone Night Traveler

george drew Talbot’s Chance

jimmy kindree Emerging

michael colonnese Half-life: A Poem for my 45th Birthday

diana hume george This Library Still Stands

Years ago I interrupted Philip and Jill Gerard’s marriage preparations just off the grounds of Chautauqua to ask them, on behalf of the Writers’ Center literary arts board, if they’d accept the board’s invitation to edit the institution’s journal. It would have been more decent to let them get married and leave on their Erie Canal honeymoon first, but the board was in a hurry to obtain their commitment. They said yes, but if I’d waited even an hour, it might have been too late—they were about to disappear. There’d be no reading business emails on that honeymoon vessel, and who would call a couple on the phone during their honeymoon? So for years thereafter, Philip would now and then lean over to me and in a Marlon Brando godfather rasp he’d say, “You come to me on the day of my wedding”—he’d pause—“and you ask me to edit a journal...”

Starting with the next issue in 2008, Philip and Jill Gerard’s indelible imprint has marked every subsequent page of Chautauqua. In the wake of his suddenly leaving us all, I recently wondered with Jill at how Philip—who so often wrote about war and loss, violence and racism, and was unafraid to confront forces of true evil inside the covers of more than one book and steadfastly in his civic life—remained at heart an inveterate optimist. With Martin Luther King, Jr., he seemed to genuinely believe that the arc of the moral universe ultimately “bends toward justice.” Revisiting his editorial introductions to the issues of the journal, I see why.

Here, perhaps more clearly than any other single place, he recollected his early adventures, his immigrant family’s love of America, his sense of wonder, the landscapes of his youth, “the clean white arc of a baseball flying across a powder-blue summer sky,” and “the golden territory of his boyhood, now a landscape of memory and words.” He believed in the human story, “still unfolding, still an idea and an ideal.” He meant America, but the entire human project as well, because “All

the great ideas of philosophers, the sublime experience of art, the literature of the ages, are available for the taking: a person must simply make the effort. It’s our mythology, a glorious one, if you ask me.”

During the first years of our acquaintance as mentors at Goucher College’s MFA program in creative nonfiction, Philip and I regarded each other from a respectful distance. I’d used his texts in my courses at Penn State, and he’d read (and, I later learned, taught) a couple of my essays, but we weren’t pals. All of our outward signifiers were at odds—he was an imposingly Hemingwayesque guy, I an aging ex-earth biscuit swathed in scarves. He was a journalistic-facts fellow, and I was (wrongly) associated only with memoir. Both were cases of mistakenly narrow identities, but between new colleagues, those stereotypes kept us fairly formal with each other.

One August in the first years of the new century, in the middle of the night I wandered outside to the front steps of the Sheraton Hotel in suburban Baltimore where we stayed during Goucher residencies. I can no longer remember if he was already there, or if it was the other way around, but suddenly there we were, both sleepless with personal issues, both aware we had to be up in a few hours to be fully present for our students. That much we knew of each other, that we were dedicated to the task. Quietly, tentatively, line by line—“What are you doing out here in the middle of the night in this heat?” and “I was about to ask the same of you”—we confided one small thing, then another, then another, until we’d exchanged confidences that surprised us both. He was in love and missing Jill. He’d soon become a stepfather, and I had experience in step-parenting. I was concerned about a grandchild’s addiction and my own enabling tendencies—and he was great at setting boundaries. Our perceptions were useful to each other.

A friendship now two decades old was born there, and we both knew that if not for that chance encounter, we might never have seen through the thicket of each other’s contrasting personas. Thus did we graduate from seeing each other only at Goucher College to gathering together yearly at Chautauqua. Jill, with whom I immediately connected, had grown up going to Chautauqua, so when I asked Philip to teach nonfiction at The Writers’ Festival that I co-directed, he’d already started to

know the place with Jill. Later I’d go to UNCW to teach for a term. I also visited the publishing lab and editorial meetings where Chautauqua still comes into being.

Quite simply, it is beyond belief that Philip Gerard is no longer with us. It is literally beyond belief for Jill, and so many of their friends and fellow writers are trying to hold Jill in a cocoon of supportive love, because we too cannot suspend our disbelief, lesser though it be. I have moments of accepting his absence these several months later, but not many. What the African philosopher Amadou Hampâté Bâ said of any death of a distinguished personage—that with their passing, a great library burns down—would be true of Philip, but it is not burned to the ground, because much of that library still stands in the form of his many essays and books, his songs and talks and interviews. So I hope you’ll indulge me in the way I can best continue this, which is by speaking directly to him, a thing I do each day.

Philip, I write this as if you were still here, because it feels as though you are. No, not “as though.” You are. I can feel your presence. We all do.

I don’t usually feel presences from beyond this life, but you are more certainly present than anyone near me who has died in these recent years, even though there are suddenly many of them. All the recent others, when they left, were gone to me, even my brother, whom I loved.

You, Philip, you’re still here, whatever that means. I mean to figure out what you’re doing here. It’s not the same as how they say a soul lingers, hovers a while not understanding what’s happened before going on its way toward a next place, a next form, or a saving oblivion. Your presence feels different. It has to do with your powerful writing, your place in the lives of hundreds of fellow writers, students, peers. For so many of us, you’re still here speaking.

But where is this here? All the tributes to you online are in the past tense: what you meant to someone, the great lessons you taught. I have internalized you long since. This is the case for others as well. As our colleague Maggie Messitt returned from South Africa after nearly a decade, she was forced to re-envision her trajectory, one already grounded in telling true stories, and it was you, the writing life you exemplify

and embody, that she had in mind when she decided to craft a life writing books and teaching writers.

Within a few years, even though you are slightly younger, you became for me the ethical summit of what it is to live as a writer for one’s entire time on earth, book upon book building a purpose-driven life, one that must wrest meaning from every experience, especially every tragedy, such that you became a voice of transparent moral authority itself—what our mutual colleague Dick Todd called authenticity. I always cared what you thought, and when you expressed approval or respect for my words, I knew I’d done something right.

Unlike many who reach such a place in life, wherein existential struggle is joyous and determined, restless and wrestled to the ground, you’ve never stopped wanting to bring that example to apprentice writers. Your focus on whatever you research and write has always been laser-like, and you certainly have no time for fools, but you always share what you know, convey it, communicate it endlessly to those in our field. And what is our field?

We believe in telling true stories, reported or from our own lives, as a way to make meaning, to thrive, sometimes even to survive in ways we can respect. You came to narrative nonfiction from fiction. You were a novelist before you literally wrote the book on Creative Nonfiction, then Writing a Book that Makes a Difference, a perfect title for the goals you continued to meet, fully embodied in your historical nonfiction about World War II or racism in America through regional history in the Carolinas. The made-up stories were always about the real stories as well, the way that Cape Fear Rising came to rest literally decades later with The Last Battleground. Your writing was always in pursuit of large truths, whether personal or historical, those being something you believed in much more than I. You’ve always seen words as the way to search out truth—uncover it, hunt it down, even create it. Your stories that tell truth took the form of music as well as print, and lord, how you made us sing through summer Baltimore nights and at Chautauqua.

I used to think you were wrong when you told our apprentices that they, too, could write not only essays, but books that would end up between covers. But you were right. I have a wide shelf of books that we

and others helped bring into being, books one atop another. So often it was you who first planted that seed in them, made them believe that they could do it, told them they were writers. You have often believed in apprentice writers before they believed in themselves. Certainly before I did. You are so generous that the grave cannot contain you. Your belief in what we can learn from the stories we tell, the stories we listen to, is an eternal kind of verity.

You and Leslie Rubinkowski go back even farther than you and I do, so although at first we could barely speak, now we turn to each other to stay grounded. We have to decide what to make of this, your strange disappearance from this plane, your lack of mortal form. It’s our responsibility to do something with your absence in our own lives. What Leslie says applies to me as well:

“The day after Philip died I sat by a window in a restaurant staring out at traffic, staring into space, scrolling on my phone, where I fell into an essay Nick Cave wrote about his son Earl, whose twin brother, Arthur, died without warning. Arthur died over a school break, and on his first morning heading back to school Earl told his parents, ‘What happens now is for Arthur.’ That’s how it is, how it will be, because what had happened the day before made no sense I could see. But what happened every day after would, at least in one way, because it would be for Philip.” Yes, you mean that much.

Muriel Rukeyser’s poem “Double Ghost” ends with “Do I move toward form? Do I use all my fears?” You were, you still are, always moving toward form in our minds. I think you used all your fears as part of your creative fuel. I wrote on the back cover of your Patron Saint of Dreams about your nuanced integrity, the way you view writing as a calling, arising from the conviction that words can matter to the sacred duty of figuring out what we’re doing on this earth. They are such great essays, especially those that address mortality. I think you were, and are, as prepared for death now as you would ever be—that is, fully, and not at all.

We are all headed where you’ve gone, and if we could back up far enough for deep perspective of the kind you always championed, and see our place in the firmament of storytellers, and contribute our share

of making plain-clad mortals into a mythography of the remarkable ordinary, we’d see that there’s not much time between your departure and ours, as those of us who are your peers work our way through the stories we tell, and the truths those stories contain, and make room for the incoming generations of writers who want to find their own best ways to be, like you, kind, compassionate, generous, and brave.

When the poet Anne Sexton died, her friend Maxine Kumin felt “remaindered in the conspiracy,” and we—those of us who worked alongside you, read you, listened to your voice, exchanged Al Swearengen monologues from Deadwood or lines from The Three Stooges, sang along with you and your guitar, discussed great essays and great battles and renovating histories—we will remain in that conspiracy the rest of our own earthly days. You’re right here with us, inside us, until we too move along. I have compared the aura of authoritative wisdom in some of your essays to Wordsworth’s “spots of time,” spaces the poet said contain a virtue that can “lift us up when we are fallen.” In “Bear Country,” about almost dying when you were 19, and then again 25 years later, the epigraph you chose from Wordsworth says it all: “And all that mighty heart is lying still!”

Or not. Those of us who loved you have your heart transplanted into us, Philip Gerard. Steadily it beats.

Our destiny is frequently met in the very paths we take to avoid it.” “

—Jean de La Fontaine

Cass and I put polonium’s final neutron in place and stepped back to admire our work. The model, made of eighty-four black marbles (protons) and one hundred and twenty-six white marbles (neutrons) glued together in a sphere the size of a mini soccer ball, was beautiful. Despite sweat running down our faces, we lingered inside the garage to admire our work. We’d been building atomic models for several days.

I’d read books about Marie Curie discovering radium and polonium, and, as a nerdy boy about to enter the eighth grade, I was already working on my fall science project. Some atoms, like polonium, fell apart, others did not. Nowhere could I find the reason why, and I hoped, if I built enough models of different atoms, I might discover the answer.

I explained to Cass that the strong force held the nucleus together, but sometimes it didn’t. “The glue,” I said, pointing at our model on the workbench, “represents the strong force.”

“They should call it the love force,” she said. “Love holds people together.”

We were standing shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip, and I didn’t know if she was talking about us or atoms. We’d known each other two weeks and had skipped the dating phase and gone directly to something unnamable.

“Marie and Pierre Curie worked side by side in a hot lab,” I said, hoping she might see the connection between the Curies and the two of us working in a hot garage.

Cass threw her arms wide. “Well, Pierre,” she said. But before she could finish the thought, her outstretched arm knocked a stack of old newspapers off a cardboard box on the workbench, revealing a half empty bottle of Old Grand-Dad whiskey.

She looked at me. I looked at her, and we both looked at the bottle. “My dad’s,” I said.

On Easter, I found a bottle on the back porch when I was hiding Easter eggs for my cousin. A bottle sometimes rattled beneath the driver’s seat of the car, and one was often hidden behind the jug of floor wax under the kitchen sink. Until that day, I’d kept my father’s drinking a secret from Cass. Discovering the bottle made me angry. I was embarrassed. His drinking had invaded our time and place.

Cass reached for the newspapers and was about to put them back on the box when I grabbed the bottle. I don’t know what I was thinking or trying to do. Maybe I wanted to show her how I felt. Maybe I was trying to get even with him for the nights he was drunk. I carried the bottle to the alley and poured the smokey, sweat-smelling whiskey into the gravel. I tossed the bottle in the trash.

“Will you get in trouble?” she asked.

If one element could transform into another, say polonium to lead, then alcohol transformed my father from nice guy to dangerous. I felt good dumping it out, but I could tell from the look on Cass’s face that she worried. “No,” I said, “I won’t get in trouble. Well, maybe.” He had other bottles stashed away, and I hoped weeks would pass before he discovered this one was missing.

i made my escape the next morning before sunrise. Afraid the kitchen floor would creak, or the back door screen would groan, I slung my backpack over my shoulder, dropped out my bedroom window, and tiptoed through the wet grass to the garage. As I lifted my bike off the hooks, I glanced at the workbench to admire our atom, but the polonium nucleus had been smashed and marbles were scattered across the dirt floor. My breath caught in my chest. Our work destroyed! I started picking up the marbles, dropping them in the box that once held my father’s liquor and quickly realized if I continued, I’d be late meeting Cass. I turned back to my bike. I didn’t dare push it out the gravel drive, which ran by my parents’ open bedroom window, so I rolled it through the yard to the alley and from there, jumped on and rode as fast as I could.

The morning was warm and sticky, and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky when I arrived behind the lumber yard where Cass was waiting. The town was quiet, so we whispered, afraid to wake a sleeping dog or be heard through an open window.

“Ready?” I asked, doing my best to hide how upset I was over our smashed model.

Her ponytail hung from the back of a red baseball cap, and a hint of pink colored her lips. Visible beneath her white t-shirt was a bra, which I pretended not to notice. I felt sloppy in my faded Ohio State

T-shirt and worn Converse shoes. I wished I’d worn something better, although I had no idea what that might be.

She nodded. “You?”

Cass had been living across the street with her grandparents while her parents managed their move from North Dakota to Florida, and we’d been seeing each other daily, shooting basketball behind Doc McMullen’s garage, playing Hearts on her grandparents’ back porch, studying constellations from a blanket in their backyard, and riding our bikes along the Hocking Canal. For several afternoons, we’d been building atoms that were now smashed and broken.

The sun rose above the railroad tracks on the horizon, and crows cawed from the trees. What we were about to do had been planned for a week. It was her birthday and her last day with her grandparents before her parents arrived and took her to their new home in Tampa. We were going to celebrate. Just the two of us.

“I’m ready,” I said.

She took off on her bike and I followed close behind.

i’d seen my father throw a plate of spaghetti at the wall during an argument with my mother. There was a hole in the bathroom door from his foot, and he’d once been so mad at the car for overheating that he floored the gas until we were flying down the road at over ninety miles per hour while he screamed at the engine, daring it to blow. But I’d never seen him as mad as he was the previous night when he came back from the garage where he discovered his empty bottle in the trash.

He accused my mother of dumping the contents, and they got into a fight, yelling at each other, tossing threats back and forth and slamming doors. Overcome with guilt and hoping I could end the argument, I confessed I’d poured the whiskey in the alley. I tried to think of an excuse as to why I’d done it, but none came to mind, none that I could share.

My father pulled the belt out of his pants. “You stole my stuff!” he yelled. He took a step toward me, and I braced myself against the wall next to their wedding photo, a photo in which they are both smiling.

My mother stood with her arms crossed and didn’t say a word in my

defense. Maybe she was thankful his anger had turned on someone else and given her a break.

Then, a miracle, the doorbell rang. Someone, I thought, had heard them and was coming to warn my parents they were calling the cops. My dad scrambled to get the belt back in his pants, but when he got to the door it was a high school boy selling raffle tickets to support his American Legion baseball team.

I ran to my room and closed the door. A short time later it exploded open, and my father stood there, red-faced and panting. “If you ever, ever, mess with my stuff again…” His chest heaved like he was having a heart attack. “You’re grounded. Don’t leave this house. Don’t leave your goddamned room until I say so. Hear?”

I nodded.

“Hear?” he yelled.

“Yes,” I said.

“I’ll show you what it’s like to have your stuff destroyed,” he said.

cass didn’t ask if I’d told my parents where we were going or if my father had discovered the empty bottle. I wondered if his yelling had been heard across the street. I didn’t mention what had happened to our atomic models.

We stuck to the alley that ran behind the feed mill and the creamery and then followed the railroad tracks out of town. Gravel crunched beneath our tires. An approaching train thundered past. Just beyond the high school, we turned right and pedaled down a short hill to the towpath that ran along what was left of the Hocking Canal. We’d successfully made our escape.

Butterflies swirled up from milkweed and goldenrod as we raced where plodding mules had once pulled barges. We were flying. Cass led the way, although I could have passed her if I wanted, if the path was wider, but I was happy to follow, happy to watch the strip of exposed skin between her shorts and shirt. She stretched out her hand as we passed through clouds of butterflies and whooped with delight as the bikes bounced over dips and bumps on the path. I patted my pocket, double- and triple-checking I had the money.

We worried about getting caught, about an unknown force stopping us or pulling us apart, but the farther we got from town, the safer we felt.

Twice, we crossed a road that bisected the canal and towpath. Rows of knee-high corn grew in the field on our left and old sycamore and oak trees had taken over much of the canal, which no longer held any water. When the path widened, I moved up next to her, and we rode side by side.

Paranoid, I glanced back to make sure we weren’t being followed. To avoid getting caught I’d mapped a roundabout way down dirt roads and along the canal to our destination. It added miles to our route, but we’d be safe. We were in no hurry.

“My grandfather worries about us spending so much time together,” she said. “He worries that we might have sex, so I didn’t tell him about today. Are you obsessed with sex?” she asked. “Boys often are.”

I wondered how she knew boys were obsessed with sex. “Not obsessed,” I said. “Curious. My father threatened me, said I had to wait until I was married, or I’d ruin my life.” I didn’t mention that he’d disown me if he knew I was out of town, riding along isolated woods and quiet backroads with a girl.

“My mother gave me a book with color pictures,” she said. “It seemed…”

I waited.

“Gross.”

I didn’t know what to make of that. “And?”

“But I understand the mechanics.”

I’d never talked with a girl, with anyone, about sex, but with Cass it was as natural as our nightly discussions about basketball, school, science, and art. This was the day she turned thirteen. Maybe that was why she was talking about it.

“I’m wearing a bra,” she said. “It’s not a trainer.”

No girl in my class would’ve ever announced she was wearing a bra, not to me anyway. “A trainer? What was it training?”

Cass laughed so hard she stopped her bike, got off, and let it fall to the ground. She held her sides. She said something I couldn’t understand although I caught the word training.

I wanted to repeat my question just to keep her laughing, but I was laughing, too, and couldn’t get out the words.

“Well,” she said, when she eventually gained control. She picked up her bike and we were off again. She led the way and I’d call out, “Turn left up here,” or “Take the next road.” From time to time, I could see her shake her head and hear her laugh. I didn’t know what was so funny.

Although there was a small café back in town, we wanted to be alone, and I’d decided the safest place was the Sonic Drive-in outside Nelsonville, about a ten-mile bike ride if we stuck to the back roads. We’d eat at one of the picnic tables in the park next to the river then ride to the bakery where I’d pick up a small cake. I thought I knew the back way that would take us off the main roads, but everything looked different from the bike, and I’d been distracted by that strip of exposed skin on her back. The canal abruptly ended, and we turned onto a narrow country road that passed through a covered bridge. We briefly stopped and watched the muddy creek run beneath our feet. Ducks swam along the bank and dragonflies darted over the cattails. “Nature’s art,” Cass said.

Returning to the road, we resumed a steady pace, hugging the berm although there were few cars. The day was getting hotter, and the sun should have been behind us but was off to the side. We flew down a long hill and slowly pedaled up another. Despite my careful plans, I had no idea where we were.

“Cass?”

“Yes?”

“I’m lost.”

We stopped, got off our bikes, and stretched our legs. The air felt as hot and steamy as the boys’ locker room after gym class.

“Well,” she said, plucking a blue chicory blossom from beside the road and sticking it in the back of her cap, “you’ve taken us to a pretty place.”

“Do you want to turn back?” I asked.

She looked at me as if I’d suggested something unthinkable, something like having sex. “No! Let’s keep going.”

“But I don’t know where we’re going.”

“I think you do,” she said.

We drank from the water bottles in our backpacks and looked at the surrounding hills for a clue as to where we were. Satisfied we were lost, she jumped on her bike and began to pedal. We went around one curve and then another. Despite the heat, I was in heaven. I didn’t want to ever go home.

We didn’t discuss the future, my father’s threats, or her grandfather’s warnings. We didn’t moan about it being our last day together—that we would meet again was understood. She acted as if we’d landed in a foreign country the way she oohed and awed at the wildflowers, the tall trees, and the big fern growing alongside the road. A pileated woodpecker flew over our heads, and a fat groundhog stared as we passed. We welcomed the cool shade as the road ran beneath a canopy of leaves. Then, just when I thought we were hopelessly lost, I smelled bacon. Cass smelled it, too, and let out a hoot that sounded like an owl. Around the next curve, in the middle of nowhere, we saw a diner sitting back in a cove of trees.

“Magic!” she said, letting go of her handlebars.

We leaned our bikes against an old oak. “Hope this place is okay,” I said. “I’ve never been here.”

“The Dew Drop In,” she said, reading the small sign nailed to a post next to the road. “It’s perfect.”

There were two cars, several pickups and a couple motorcycles in the parking lot. I took a deep breath, stood straight, and pretended I was older than I was.

“We should hold hands,” she said as we approached the door. “Couples do that when they go out to eat.”

I took her hand and a warm buzz ran through my body.

Inside, the restaurant smelled of fresh baked bread and coffee. A waitress carried plates stacked with pancakes, waffles, eggs, sausage, and ham. Small pitchers of maple syrup waited on every table. A waitress standing near the front door, looked behind us as if expecting our parents to follow.

“You waiting for someone?” she asked.

“No,” we answered in unison.

“You here to eat?”

“Yes.”

“Go ahead and sit wherever you like,” she said, smiling as if amused by our presence.

I was taller than my brother, who was going to be a senior, and Cass—with her lip gloss and bra—looked like a high school girl. But we still attracted the attention of the curious sitting at the counter as we walked past a display of pies to a corner booth.

Cass loved everything about the place, the purple coneflowers in drinking glasses on the tables, the sports memorabilia on the walls, and the view of the trees across the street. She was in love with life and the moment.

While we waited, I scanned the restaurant for familiar faces, hoping I didn’t see any. The last thing we needed was someone telling my parents or her grandparents they’d seen us here, wherever here was. I shuddered to think of my father’s reaction. Isolation? Banishment? The belt?

A waitress brought two menus and asked what we’d like to drink. After we ordered Cokes, Cass and I traded facts, art for science. It was a game we’d played one night while rocking in the swing on her grandparents’ front porch.

“The sky gets a lighter blue as you get closer to the horizon,” she said.

I tried to think of the scientific reason, air scattering blue light, but she said it was my turn before I could come to any conclusion.

“Okay,” I said. “Try this. Marie Curie named polonium after her home country, Poland.”

“Good one,” she said. “Georgia O’Keeffe was still painting when she was in her nineties, even though she was almost blind.”

I nodded in recognition of an interesting fact. “Here’s one. When Marie and Pierre Curie married, there wasn’t any special ceremony. They just bought each other bikes.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No.”

She looked out the window at the tree where we’d leaned our bikes. “Nice,” she said, grinning.

Then, after the waitress brought our Cokes and we ordered pancakes, Cass mentioned the color of Jesus, which, I assumed, had something to

do with art. “You can tell your brother Jesus is white in North Dakota,” she said.

My brother was at church camp. He wanted to become a preacher.

“What?” I asked.

“Yeah, when we lived in Texas there were billboards all over the place with paintings of a brown Jesus. That’s the way I thought Jesus looked. Brown. Then, when we moved to the airbase in Minot, North Dakota, Jesus was white on the billboards, I mean really white, like he was albino. Don’t you find that strange?”

Although I didn’t go to church with my parents and brother—long story—I agreed to tell my brother about white Jesus.

Our food arrived, stacks of pancakes and links of sausage. First thing I did was stab at one of the little sausages with my fork, and it bounced off my plate and onto the tile floor. Before I could pick it up, a waitress came along, swooped it up, and brought me a new one. I was embarrassed, and then Cass tried to stab her sausage with the fork, but the skin was tough, and the sausage flew off the table and landed in the same spot as mine seconds earlier. “Quick,” she said. “Get it.”

I picked it up, wrapped it in my napkin and tucked it under the edge of my plate. I noticed that the two sausages left a significant spot of grease on the floor.

As I ate my pancakes and talked with Cass, a waiter on his way to the kitchen with a tray of dirty dishes approached our table. I could see what was going to happen and wanted to shout a warning, but it was like trying to yell in a dream. No sound came out. His heel hit the grease spot, his leg shot out from under him, the tray went up in the air, and he went down, followed by crashing glasses and plates.

It was the funniest thing I’d ever seen. For a brief second the waiter, a tall guy, was suspended in air, and then boom. He wasn’t hurt and quickly got to his feet. Soon, Cass was laughing, too. We were acting immature despite our efforts to look and act like adults. I thought we’d get kicked out, but I couldn’t stop snorting and shaking. I put my head down next to my plate. I wanted to crawl beneath the table. Every time I thought I’d gained control, I’d look at Cass, and we’d both start laughing again. Only when the mess was cleaned up and our water glasses refilled

did we settle down and resume eating our pancakes. We didn’t touch the remaining sausage links.

The waitress stopped to ask what kind of pie we’d like. Before we could answer she rattled off the possibilities.

“No dessert, thanks,” we said.

“It’s already paid for: your meal, dessert.”

We looked around the diner, the muscled guys sitting at the tables and the old men sitting at the counter, a couple my parents’ age in a booth where a waitress and cook were singing “Happy Birthday.” No one gave any indication of having paid for our meal and a slice of pie. “Who?” I asked.

The waitress shrugged.

I started to mention that it was Cass’s birthday, too, but Cass caught my eye and shook her head. She turned to the waitress. “Blueberry.”

“Cherry,” I said.

Getting our meal paid for by a stranger made the morning and getting lost, finding this place, being together, even more special.

I leaned forward, whispered. “Who do you think it was?”

She scanned the diner. “The couple in the booth. It’s his birthday or hers and they see us as a younger version of themselves.”

I studied the couple. They were sharing a large slice of pie and chatting away, but they didn’t return my look. “Maybe,” I said.

A deep rumble shook the window. At first, I thought it was a train, but we hadn’t passed any railroad tracks and the second rumble, which closely followed the first, sounded like thunder. The trees outside blocked the view of the sky, but it appeared darker than it had been only minutes earlier.

“Think we should be going?” Cass asked.

What I wanted was to sit in the booth with Cass all day. Milkshakes and Cokes and slices of pie. Had we been older, I’d’ve asked her to run away with me.

She reached across the table and put her hand on mine. “Me too,” she said, apparently reading my mind.

“As soon as we finish our pie,” I said. “Maybe there’s a shorter way of getting back. I’ll ask.”

Another loud boom shook the diner, and everyone looked out the window, although there wasn’t anything to see. It wasn’t raining. The leaves weren’t stirring, and a paper cup and straw lying in the road had not moved.

When the waitress—her name tag said, Ethel—returned to see if we wanted refills on our Cokes, I asked for directions. “We got lost on the way here,” I said.

“A lot of people do,” she answered. After asking where we wanted to go, she pulled a pad out of her apron pocket and made a map, and then went over it with us, the turns and where we were to be careful. “One nasty hill,” she said.

And then we were on our bikes. “I think the rain will go around us,” I said.

And then it began to rain.

“Your future in science isn’t forecasting the weather,” she said.

We’d gone a mile, maybe a little farther, when the sky opened, and what had been a steady drizzle turned into a torrential downpour. The wind rocked our bikes. The rain stung our faces.

“You okay?” I asked. I was soaked. My shoes, socks, underwear.

“I’m good,” she said.

At the first intersection, I pulled the map out of my pocket. The ink was smeared, and the map fell apart.

Lightning flashed and an instant later the crack and boom of thunder echoed in the surrounding forest. “Let’s look for shelter,” she said.

There was no shelter, just trees and empty road. I thought we might be killed.

We rode on.

A few hills and curves later, with the rain coming down in waves, an old pickup truck pulled up beside us, and the passenger side window came down. A woman my mother’s age, the woman I’d seen sharing the slice of pie in the diner, motioned for us to stop. “Throw your bikes in the back and climb in. No room up front but you’re already wet. We’ll take you home.”

I didn’t know her and didn’t get a good look at the driver, but we were desperate.

“You know where we live?”

“We’ll find it.”

I lifted my bike on the truck bed and then Cass’s. We stepped on the bumper and climbed over the tailgate, gave the driver a thumbs up, and we were off.

“That’s the man and woman from the restaurant,” Cass whispered although whispering wasn’t necessary what with the noise of the rain beating against the roof of the cab and the bed of the truck.

We sat with our backs against the cab. The warm rain felt good. When lightning flashed, we scooted tighter against one another. Cass threw one leg over mine, and we held hands. The couple in the cab sang along to classic rock songs on the radio. “Since we’ve been together… Loving you forever.”

She had a good voice. His was deep and gravelly and he added flourishes that made us laugh. I turned and saw the backs of their heads. A baseball rolled back and forth on the dash.

They dropped us off behind the lumber yard. I wondered who they were and how they knew where to take us. Had Cass told them when I was lifting the bikes onto the truck?

“A perfect day,” Cass said as we walked our bikes through puddles. The rain was like a curtain, and it was easy to believe it hid us from the rest of the world and what would come. We didn’t know when we’d be seeing each other again. We stopped inside her grandparents’ garage, wrapped each other in a tight hug and held on as long as possible.

Sometimes, miles from home, you find wings just the way you like them. The beer is cold and cheap; the bartender doesn’t care about you and things you might say. These are small blessings: a dive that takes you in this way, comfortable enough to pay you no mind until your lager runs dry. Pool balls clack, a wager is made, and you decide to pray

to the bones piled up on your plate, thank them for all they’ve given you. A local feeds a buck into the jukebox and it’s not late yet,

you think. It’s a song you don’t hate from the nineties, full of pity and regret. The tender shimmies, putters with the liquor bottles. Her body language won’t prattle, show those things you’re not meant to see.

In the parking lot, you feel drizzle on your face, just as predicted.

Soon it turns to rain. Planted, still you fail to leave. Trees begin to sway.

My husband and I moved to North Carolina in 2015 after retiring from the military. We bought a house, the first we had purchased together, two blocks from the Intracoastal Waterway. No strangers to hurricanes, having been stationed in the Florida Keys and other Hurricane Alley locations before, Jim and I knew how to prepare for them and that often the best option was to evacuate.

Just because I knew how to prepare for hurricanes and survive them didn’t mean I liked them. Summer after summer, I braced for Matthew, Irma, Maria, and other big storms, some named, some not. The annual onslaught started to feel personal, as if climate change had me in its crosshairs.

In 2018, the mother of all storms came calling. Jim and I evacuated and Hurricane Florence swept in with a vortex and deluge that pummeled our town for four days. She devastated Topsail Island, which sits across the Intracoastal Waterway from our neighborhood, and breached the roofs of houses in our cul-de-sac, saturating and destroying everything inside of them.

When the highways and roads were clear of debris, we returned home. Expecting the worst, I was surprised to see our house standing and mostly intact. Planks of siding were loose here, pieces of trim were broken there. Water had intruded under the front door and through two windows. We lost a beloved river birch about thirty feet tall. In a final act of grace, it had collapsed on the lawn, parallel to our house but not touching it.

Jim and I did what humans do—set emotion aside, carry on, reacclimate. We repaired the siding and trim, had the floor refinished, and had several windowsills replaced. We planted a red maple where the river birch made its last stand.

In 2020, when Hurricane Isaias rumbled our way, I felt like an old hand. Tempting fate, we did not evacuate. As the wind howled and fat

raindrops soaked the young red maple, we sat on the front porch in rocking chairs, beverages in hand, and marveled at the drama of Isaias. Inside the gutters and downspouts, a chorus of tree frogs was singing. Absent the usual suburban sounds of dogs, lawnmowers, and kids on scooters, I tuned in to the frog soundtrack. Over the rain, I could just make out the lyrics.

tree frogs are chirping tonight in the hurricane water is water…

The Bronx is like this: stray things show up at the door— menus, Mormons, someone else’s morning paper.

And now an insistent cat circling the stairwell, demands echoing on cracked marble, tail an erect counterpoint to dirty paws.

It’s like this everywhere— even in Missouri, where I was born. Does everyone know how these things end?

Feline in the apartment, on the bed, the couch; fall light slants through the window to warm him, turns his whiskers golden.

Shadows lace in, too, from the fire escape, where sparrows crowd over stale baguettes, hopping like brown leaves tossed in the wind.

In this late light, the cat’s fur under my fingers is soft and rich. And I know the color, but cannot name it. Butternut, I say, honey, ripe wheat.

All things I moved here to get away from. Beyond the fire escape, beyond the traffic, miles beyond— my mother in her flat, wide yard uses suet to bring birds to her.

She sends me pictures in which they are small specks, and the surrounding fields swallow them up, resolute and golden.

She won’t visit me, but when the phone rings, she answers, and her voice is warm and soft. Champagne, she says—

the word a small gift offered across a line that hisses like wind in cornfields— The color of your cat is champagne.

I watch from my window as the crystal axe of winter shatters the yard’s blank mask into luminous frost stars.

Sudden ribbons of muscle and fur, two red foxes, tails on fire, erupt from their house of snow. Across the channel of unknowing,

a restless wish rises, an urge to escape my body’s border. Across the yard the foxes surge. The sky lets loose its white shrapnel. Leaves shiver, numbed into tatters. Wherever I go, I want to leave, I suffer.

“Ihearit’s flat where you come from,” the apartment manager says, tapping my driver’s license.

“So flat,” I reply, “that you can watch your dog run away for two weeks straight.”

As flat, I keep to myself, as the lines on vital signs monitor when they don’t have anything to keep track of anymore.

Like most folks around here, she’s got buckets of friendly chatter. “They say the sky’s big out there.”

I was brought up polite, so I don’t tell her Montana’s the state that nabbed that slogan. And I don’t tell her how big the bowl of the sky can be—so big it curves down to swallow up the roads on which the man you wanted to grow old with will never drive again.

She swings open the door of the furnished studio. “What brings you east?”

The studio’s balcony overlooks a hill alight with fall leaves. “I didn’t start out going east. I almost made it to the Rockies, but Beulah didn’t like the steep grades.”

She asks, “Who’s Beulah?”

“My hatchback.”

There had been no point in staying after the funeral, so I filled the tank and put mile after mile behind me, driving west as far as the foothills, where Beulah groaned and whined and threatened to overheat. I changed course; it didn’t matter where I went, so long as it was away from where I was before.

Navigating on the east side of the Rockies was simple. I kept the jagged line of peaks on my right shoulder. I stopped somewhere in Colorado to buy a suitcase; I was tired by then of keeping my things in a plastic bag. But Colorado wasn’t far enough away, and I kept driving.

I’d glance in the rearview mirror to check the progress of the gray hairs—so few that I had a name for every one of them—that tangled with the dirty blonde ones. There were new and faint fans of lines at the corners of my eyes.

Fraser’s eyes were the lightest of blue, the color of a June sky at nine in the morning. One day as he stared at the bedroom ceiling, I realized that, side-on, his pupils were as clear as glass.

“I can see through your eyes!” I exclaimed.

He rolled over and drew me close. “That’s what it’s all about, seeing the world through each other’s eyes, don’t you know?”

It was so perfectly poetic that I figured it’s what I must have meant all along.

The sound of ruffling papers calls me back to the present. The apartment manager flips through documents and says, “We’re almost ready to sign, but you didn’t fill in the emergency contact.”

Fraser was my emergency contact, but I wasn’t his. He never replaced Sierra’s name after he moved out of their house, so she was the one the police called that day.

“Let’s go to Seattle or somewhere out there,” I had suggested the week before at Larson’s Fin Dining.

He pushed couple of fries through the gravy on his plate.

“Nothing’s keeping us here,” I reasoned. “Everyplace needs bartenders.”

“You think?” he asked.

“And hotels always need someone for evening shift.”

We, the only night people in town, were made for each other—we loved pancake-thin pillows and the dark edges of overbaked cookies but dreaded perky morning people, mayonnaise, and the tuna hotdish that Larson’s Fin Dining prided itself on. We were orphans, too. Fraser was orphaned by misfortune. I was not an orphan in the legal sense, but it was less complicated to say I was than to explain how much sunnier life was out from under my folks’ corrosive and endless disappointment. Away from them, I became almost as easygoing as Fraser.

Sierra was nothing close to easygoing, and only the diminished romantic opportunities of a pocket-sized county seat in half-deserted farm country could explain why Fraser ever married her.

There were a couple of million reasons why they separated, but only two reasons they never divorced.

The first he said out loud, “It’d cost me too much in alimony.”

He never spoke the second, but it was understood by all: It was his nature, one that seemed at odds with his imposing ruggedness. He coaxed ladybugs off the inside of his window screen and onto his fingertip to release them outdoors; he absorbed the deep hurt and brittle anger of drunken bar patrons with compassion, and he avoided confrontation at all costs.

i met sierra before I met Fraser on my third night working the reception desk of the Wanderon Inn. Laughter and off-key singing of “Happy Birthday” poured out of the everything room—the day manager, Ernesto, had christened the room; it did stints as a trade show center, meeting venue, banquet hall, and just once, in 1999, a ballroom. The cash bar at the birthday party was enough to put the motel into the black for the month, and the music had already been turned up twice.

I was checking in our only guests, an older couple who had pulled off the interstate, when Sierra came to the reception desk, arms flailing.

She inserted herself between the man and woman, rested her hand on his arm, and said, “This is important.”

Turning to me, she demanded, “Call your events manager. Right now.”

Once or twice a month, when Ernesto managed to book something into the everything room, he asked Darlene to stop by and take care of the details. It was gig work she did for a few extra dollars, not for the glory of being an events manager.

Sierra spoke as if I were hard of hearing. “I requested pink napkins. The napkins on our table are salmon.”

I put on the bland, corporate smile recommended in the training video and gave the bland, corporate response, “Thank you for letting me know about that.”

I tapped the keyboard of my computer, found keys for a room as far from the birthday party as possible, and handed them to my guests.

“Room 134. Would you like help with your suitcase?”

“No, miss, but thank you kindly.”

The cheekbones of Sierra’s heart-shaped face were splotchy with anger. “My mother’s dress is pink. So is the cake.”

“I see.”

“This is completely inappropriate,” Sierra said. “She doesn’t have to put up with this for her sixtieth birthday party. What are you going to do about this?”

“Our events manager isn’t here right now,” I said, sliding my glance to the clock, which read ten-thirty. Darlene had been gone for hours, had no doubt cooked supper for her grandkids and put them and herself to bed.

“Do you have any idea how much money we’re spending here tonight?”

The offending napkins had been on the table, glorying in their ability to clash with pink, since the beginning of the party. It would have been easy to swap them if Sierra had spoken up then. One corner of her mouth hinted at an ugly smile.

I said, “I’ll be glad to share your complaint with the day manager.”

A man emerged from the everything room, his dark auburn hair damp with sweat. He tugged at Sierra’s elbow and said, “Come back to the party.”

“Fraser, the napkins…”

“Don’t matter,” he chided her gently. “Your mom doesn’t care.”

“She’s not paying for this party. Dad and I are.”

“Your dad doesn’t care, either. Come back and have a beer.”

“I don’t want a beer, Fraser!”

“Your mom says she’s going to cut the cake in five minutes.”

“Without me?” Sierra shrieked. She turned a fierce eye on me. “You need to give me your name, and you can be sure that I’ll be calling your manger about this travesty.”

“Rose White,” I replied.

He pulled her away, and I nodded my thanks to him.

He winked at me and said, “Nice name! I’ve got a plant name, too.”

Sierra made one more trip to the reception desk, right before leaving, to let me know that she’d known Ernesto her whole life. For a few dark

moments, I imagined it would have been better if I had never left home. But there wasn’t even a main street there, not a single traffic light, no motel or anywhere else to work if you didn’t want to farm or commute eighty miles to a fast-food joint. In the quiet hours of the night, I rehearsed some excuses and calculated how long I could stretch my savings until I found another place. I dragged myself out of bed early the next day to report the napkin fiasco to Ernesto before Sierra did.

“She texted me last night,” Ernesto said.

I twisted the damp tissue in my hand.

“She texted Ben Larson, too, about the placement of ‘happy birthday’ on the cake. Ignore her.” He pushed back his office chair, turning philosophical. “Rose, life is all about when we peak, and Sierra peaked at the wrong time. Some people peak in high school and spend the rest of their lives trying to recapture the glory of the homecoming court or the basketball team. The failure-to-launch people never even get started. What’s best is to always be a month away from peaking, always nudging those goalposts and striving for them.”

I wasn’t about to tell Ernesto that his advice sounded like a recipe for an ulcer. I asked, “Sierra peaked in high school?”

“Worse,” he said. “Junior high. She’s a clique queen and always needs to feel like she won. Ben’s going to offer her a free cake; I’ll refund twenty-five symbolic dollars. Then she can look for the next thing to have a cow about.”

My grandfather had advice about the clique queen in my school. He told me to kick her in the shins, just once, but good and hard.

larson’s fin dining, where Fraser tended bar, was the only place in town that was open late, so that’s where I spent my Tuesday nights off. The barstools were newly upholstered, and the beer selection was decent.

My first time there, Fraser greeted me with a draft IPA, on him, he said, to make up for Sierra’s napkin meltdown.

I thanked him and said, “I looked up your plant name. Fraser means ‘strawberry’, right?”

“Two points for you.”

I ordered cheesy potato skins. When he served them, he told me that a man at the end of the bar had paid for them. The man tugged briefly at the brim of his gimme cap, nodding.

Fraser said, “That’s Bob Wagner, Sierra’s dad.”

It seemed that lots of people in this town went out of their way to compensate for Sierra.

I settled in to watch the game with the other bar patrons. Their cheers changed to angry shouts and then to mutters. After a bad call and a worse fumble, some of the old-timers paid their tabs and left. At the final score, those who remained swallowed the last of their beer and their pride and trickled out of the bar. Fraser turned the television off and the music down.

“Why does everyone in town call this place ‘Larson’s Fin Dining’?” I asked. “Does the restaurant serve fish?”

Fraser’s warm chuckle rippled as he wiped the worn oak bar. “Nah. There used to be neon sign that read ‘Larson’s Fine Dining’, but the E busted.”

Three weeks in, the other Tuesday-nighters already treated me like a regular, and Fraser had my IPA cold and potato skins hot when I arrived. I was always the last to leave, and conversation improved considerably once everyone else cleared out. He and I talked about everything. We talked about nothing.

“One more for the road?” Fraser asked one frigid February night. “Nope. I’ve got to get going, and you should get home to your wife.” I said it to remind myself that he was married.

Which he was, I learned, and he wasn’t. They had separated three years before. I did the math as he told his story; they’d spent more time apart than married.

For our first date, we strolled through the town park on a late March afternoon. The ice that remained in the middle of the lake was pocked and mottled. We tossed pebbles at the wind-driven ripples near the shore.

Fraser turned up the collar on my coat and snugged my hat down over my ears. “Don’t get cold.”

We started walking to warm up, avoiding slush puddles.

“Well, would you look at this?” he asked, stopping at trashcan. He plucked a stuffed elephant from the trash. “Now who’d leave this behind?”

“Gross, Fraser. Leave it alone.”

“Look, he’s got a big hole in his leg.”

He took it home, tenderhearted as he was, and stitched up the tear. He stood the elephant up. It leaned. He tilted his head and asked, “What’s your name, little guy?”

“You’re kidding. You’re naming it?” I asked.

“Says the woman who named her car.” He smiled and cleared a space for the elephant on the coffee table. “He looks like a Steve.”

I moved into Fraser and Steve’s apartment before the corn was knee high. It was a one bedroom with hand-me-down furniture, a view out the kitchen window as long as a summer day, perfectly flat and thin pillows on a new queen mattress, and Fraser’s two neat lists on the refrigerator— stuff to buy and things that needed doing.

One of those things was Sierra’s shutters. Three years separated, yet she had the nerve to ask him to repaint the shutters because they were too orange for her new crimson car.

“Fraser, why in heck are you fixing her house?”

“It’s too pretty a place to let it fall apart,” he answered. “She doesn’t know how to keep it nice like her grandparents did.”

“You’re going to paint the shutters?”

“Oh, yah. But I’ll need to buy new shutter dogs and hinges first,” he answered.

I said, “I think what would fix things would be if you told her where to get off.”

He cupped my face in his palms and kissed me. “That’s a hornets’ nest no one wants to poke. Besides,” he added, twisting a hank of my hair into a soft rope and brushing the tip of my nose with it, “I like her folks.”

“You and everyone else.”

“Come to the lumber yard with me?” he asked.

I passed, preferring an early start at work. I picked up coffee and

cupcakes at the truck stop—decaf for Ernesto because he was finishing his shift, regular for me because I was starting mine.

He had an opinion on Sierra’s request that Fraser be the one to paint her shutters: “Now that you moved in with him, she needs to assert her ownership.”

“What? Like a dog peeing on a lamppost? Ernesto, that’s immature.”

“She is immature.”

I offered him a cupcake. “And this whole town of too-too nice people never thought it part of their civic duty to help her grow up a little?”

Ernesto pinched the paper away from his cupcake. “It’s not our business. You know, her parents tried a long time until they had her. My wife and me, we always said no to our kids, and they say no to our grandkids. But Bob and Bobbie Wagner were so happy to finally have a baby that they couldn’t bring themselves to set boundaries.”

“Somebody might want to do that for her one day,” I said.

fraser and i always locked our doors. Sierra didn’t, and it was one of the things that she and Fraser fought about when they were together. He’d lock the house; she’d unlock it; he’d lock it again; she’d tell him that her grandparents never locked the house back when they lived in it.

Most people around town didn’t bother to lock their doors, either. Some of the old-timers were, in fact, not altogether sure where their house keys were. That’s the world they grew up in, or at least that’s how they remembered it—a smaller, friendlier world that existed before the interstate, one of trust and neighborliness. The crops went in; the crops were harvested. The four seasons rolled around and around.

“Not Southern California,” Fraser said one day. He had just emerged from the shower after spending the afternoon taking the shutters off Sierra’s house.

I gave him a puzzled look.

“When we go west,” he said. “Let’s not go to Southern California. I’d miss the change of seasons if we lived there.”

I hugged him so hard that he mimed gasping for air.

“Washington or Oregon, maybe?” I asked. “I’ve never seen the ocean. When should we go?”

“I ought to finish that porch first.”

I groaned.

The next day was the most miserable one of the summer, the kind when everyone said that it wasn’t the heat that got you, it was the humidity. Either one on its own was enough to lay you out that day. Fraser drove to Sierra’s to make some progress on the shutters before going to work.

I made him lemonade, the real thing, with lemons that I trekked to Walmart for. Soon enough, I learned why my grandmother preferred the powdered stuff that came in canisters. First off, you need a mountain of lemons to make more than a glassful. Second, if you drop them, they roll a lot farther than you’d think. And if you cut yourself, fishing the seeds out of the lemon juice sets your fingers on fire.

But I triumphed. I poured the lemonade over ice into an empty apple juice bottle and drove it to Sierra’s. I parked Beulah in the shade. Shutters in three different shades of green leaned against the house, quart-sized cans of paint next to them. Fraser was frowning at the shutter he’d rested on a sawhorse and a fourth can of paint to swatch.

“Lemonade!” I announced. The bottle was sweating almost as much as I was, not half as much as Fraser was.

In under ten seconds, he chugged most of what had taken me an hour to shop for and make.

“You’re the best,” he said, giving me a lemon-flavored kiss.

“I am, aren’t I?” I kissed him back. “Take a break. It’s hot.”

Sweat had glued his tee to his torso. He drank the rest of the lemonade.

I waggled my phone at him. “I found some places in Oregon and Washington. They’re beautiful. Want to see?”

He tried to make out the images on the screen before giving me an apologetic smile. “Maybe later?”

I perched on the porch rail and watched as he returned to the sawhorse and began to scrape the shutter.

“Don’t sit there,” Fraser said. “Part of the rail is rotted out. I need to replace it.”

“For crying out loud, Fraser!” I exclaimed. “Are you going to build her a whole new porch?”

“Ah, Rose, don’t be like that,” he said. “I love this old house. This is like my parting gift to it. Then we’ll head out to see all those places you bookmarked on your phone.”

He stripped off his tee and hung it over the rail. The previous day’s sun had turned his skin pink under its tan. As he worked, the muscles of his back tensed and relaxed under his new tattoo—a rose in bloom.

“You still have a key to this house?” I asked.

“She doesn’t lock her door.”

“So how about if we go inside where it’s air conditioned and have sex right on the kitchen table?”

He wiped sweat from his forehead, and, for a moment, I thought he might be considering the idea.

“That thing’s not too sturdy,” he replied. “She bought it for its looks.”

“The couch, then.”

He took a slow breath. “Rose, don’t. It’s not me you want right now. What you want is to mess with Sierra.”

I felt small, like I’d been caught somewhere I didn’t belong, and I knew he was right.

“It’s air conditioned at our place,” he offered, his eyes kind and clear and so deep I could have drowned in them. “We’ve got a couch, too, don’t you know? So let me finish up, and I’ll be home soon.”

“Okay. See you there.”

He added, “I’m gonna get that divorce. I’ll let Sierra know tomorrow.”

he kissed me and pulled the sheet up around my shoulder before getting an early start for Sierra’s the next morning. Ernesto rang the doorbell a few hours later.

“Why aren’t you at work?” I asked.

“Bob Wagner called,” he answered. “Put on your shoes. We’ve got to go.”

“Go where?”

It was 180 miles to the trauma center, and Ernesto stopped trying to distract me with small talk after the first ten. Flashing police lights dotted the place where the endless straight of the highway met the sky. The dots grew larger.

“Don’t look, okay?” Ernesto said. “He’s not there. They took him in a helicopter.”

Fraser’s pick-up was on its side; nearby, an SUV teetered upside down. A semi was parked on the median, its load of pipes scattered like pick-up sticks.

I could not help but stare.

“Rose, don’t look. Rosita! Why don’t you think of things to tell Fraser when you see him?”

I imagined us sitting on beach in Oregon, a cloud-streaked sky and majestic waves, pillars of rock standing guard offshore, gulls wheeling overhead. We’ll go there, I would say to him when I saw him. We’ll walk that beach together.

The trip to the hospital seemed to take hours. The walk down the shiny, brightly lit corridors seemed longer still. I held the image of the beach in my mind, ready to share it with Fraser. In our imaginations, we’d be together in a place of peace and beauty.

I stared at his vital signs monitor, uncomprehending. It was silent, no green lines on its black screen.

Fraser was somewhere under the bandages, tubes, and tape. His eyes were closed; what I could see of his face was slack.

“What is she doing here?” Sierra demanded.

Bob answered, “I asked Ernesto to bring her.”

“I don’t want her here.”

“Be polite, sweetheart,” Bobbie admonished, taking Sierra’s elbow and guiding her to the door. “It’s not about what we want. It’s about what Fraser would have wanted. Let’s get something to eat.”

Ernesto asked. “Do you want me to stay?”

I must have shaken my head no, because I found myself alone with Fraser.

The beds of his fingernails were a dusky blue, his hand pale and cool.

I held it to my cheek. Someone had combed the part of his hair that wasn’t swathed in gauze.

A tiny woman knocked at the door and introduced herself as the chaplain.

“How are you bearing up?” she asked.

“I should bring some clothes for him.”

She rested her hand on my shoulder. “He doesn’t need clothes anymore.”

“Oh,” I said, the reality forming in my mind. “I was too late.”

“Do you want us to pray together?”

I shrugged and said, “He promised he’d be with me forever.”

“And He is, even to the end of the world.”

“I didn’t mean God, Reverend.”

After a time that was either too short or close to forever, Bob and Bobbie returned with Sierra, who stared at Fraser as if she didn’t know him.

She whispered, “Cremation.”

I said, “I’d like to buy the urn.”

Ernesto drove me home. He and Ava made me stay at their place. She made tomato soup that I wasn’t hungry for but ate anyway.

Sierra texted me after breakfast the next day:

You can have half the ashes.

What’s the password for his phone?

Ava took me to the apartment for clothes. Without Fraser, the place was as neutral and antiseptic as the furniture display in a department store.

“Want me to pack some things for you?” Ava asked. “You sit on the couch and take it easy.”

A pair of his socks was on the floor, his coffee cup in the sink. Steve, listing to one side, stared at me with sad little eyes.

Ava hummed and puttered for a few minutes before emerging from the bedroom with my overnight bag.

She said, “Sit there a little longer if you want, and I can wait in the car.”

“No.”

“You’re ready to go?” she asked.

“You bet.”

I took Steve with me. He smelled like Fraser and kept me company when the world was asleep. He was in my hands when I awoke every night, disoriented, standing in one room or another of Ernesto’s house.

i ordered a handmade raku urn with iridescent blue glaze above, the green of endless fields below, and had it sent, at Sierra’s request, to her house.

She sent more texts that week:

The urn arrived today.

I’ll arrange the funeral.

Ushers will seat you.

Don’t wear navy.

Not only did she arrange the funeral, she starred in it—picked music that Fraser hated; held court in the first pew next to his only living relative, Uncle Leo; carried on like she was the one that Fraser wanted to spend the rest of his life with; murmured to other mourners and pointed at me, in the back pew, where the usher had been told to seat me. I wore my defiance in the form of a head held high and a navy dress.

I balked at the thought of attending the funeral lunch in the motel’s everything room. I walked to Larson’s Fin Dining instead. Ben Larson unlocked the door and let me in.

He said, “I offered her this place for free, you know.”

He poured me a coffee and topped up his own cup. I stood at the bar, more than a little lost. He led me to a booth.

“You know why she didn’t want this place?” he asked. “Because I don’t have round tables in the dining room. Jeez. Have you ever heard of such a thing?”

“Did you tell her off?”

“Yeah, no, course not. That’d be rude,” he answered. “How are you getting on?”

“I’m sleepwalking for the first time in my life. Sometimes I take pictures off the wall or open drawers.”

Ben stared into his cup. I stared into mine. We let the creaking and settling of the building do the rest of the talking. Two cups of coffee later, I walked to Ernesto’s and found him and Ava back from the interment.

Their sympathetic looks and overflowing kindness had grown, suddenly, to distress more than soothe me.

“I’m ready to go back to the apartment,” I told them.

To the apartment first, I thought, and then to Sierra’s to get my half of the ashes so I could say my own goodbyes to Fraser.

Outside the apartment door, I dropped my overnight bag, blindsided by what she had done: the lock was changed; my possessions were in an oversized garbage bag that slumped in the hallway.

My knees gave way, and I slid to the floor. For the first time since the accident, I cried. I cried loud and long enough that the neighbors cracked their doors to stare.

Shirley, who lived across the hall, came to pat my head with her knotted, arthritic hand. She was wearing her funeral clothes but had changed into aqua slippers. She nodded at the plastic bag. “It was there when I got back. So uncalled for! I saw her talking to the manager yesterday.”

I didn’t need to ask who Shirley was talking about.

“You weren’t at the luncheon. Have you had anything to eat?” she asked. “Come on over. I’ll make you tea and a sandwich. You’ll feel better with something in your stomach.”

“Thanks,” I said. “But there’s something I’ve got to do.”

The hinges squeaked when I yanked Beulah’s hatch open. I shoved in my overnight bag and the plastic garbage bag. I did something I had never done before—gunned the engine—and instead of dispelling my anger, fueled it.

Sierra was home; her car was parked out front. Fraser’s toolbox was on her porch, the sawhorse near the rail, the shutters and paint cans where he had left them.

She opened the door before I knocked. “Did you need something?” she asked with a saccharine smile.

“I’m here for my half of the ashes and the urn.”

She disappeared inside and returned with the urn. “Here you go. I’m so glad you came to your senses and stayed away from the luncheon. What would people have said?”

I swallowed the retort that was forming on my lips and walked away. I made it halfway to the car before growing suspicious of the urn’s lightness. I pried off the lid.

It was empty.

I spun around and glared at Sierra, who wiggled her fingers at me and said, “Have a nice life.”

I stormed back up the steps and hammered on the door until she shot the deadbolt. I moved to the window and slammed the glass with the flat of my hand. She pulled the shade down. I wailed in protest and rained down on her all the curses I knew. Wrung out, I sat on the top porch step, the urn still cradled in my left arm.

The need to be somewhere—anywhere—else took hold of me. My hands strayed over the urn, and I wondered where. But I intended to burn some bridges first.

Sierra’s car was unlocked. I pried open the cans of paint and poured Lincolnshire Loden onto her leather upholstery, Mediterranean Olive into the gear shift, Forest Primeval over her engine block, and Manifestly Matcha on her roof. I wiped my hands clean on her shearling steering wheel cover.

I buckled Steve into the passenger seat of my car and said, “Let’s see the ocean, little guy.”

The insurmountable Rockies stood between us and the Pacific, their profile as jagged as fresh pain. I turned south, skirting the foothills, searching for a place to call home.

The hypnotic straights of interstate sent my mind back to the accident. I abandoned the interstate to thread truer landscapes, those rich in relics of the people who had lived, loved, and died there. I held my own memorial for Fraser by a stone-choked stream, settling his urn in the shade of a silver-leafed tree. I opened an IPA, took a sip, and poured the rest out on the ground. I told Fraser that I missed him. I told myself it was time to let him go.

Still, I awoke every night to find myself standing, bewildered, inside a motel room.

a month and a half into going wherever the wind blew me, I came to a small city that lazed by the curve of a wide and glassy river.

“Should we stop here?” I asked Steve, and he nodded a yes as we rumbled over railroad tracks.

Half the businesses of the main street were shuttered, but the barbecue joint was crowded with lunchtime patrons. Their overheard laughter and conversation kept me company as I ate. When I emerged into the afternoon sunshine, I saw a woman seated under a sign—Mo’s Tattoos—sketching, a dripping glass of sweet tea next to her lawn chair.

“You’re far from home,” she said, peering over her reading glasses and pointing at my car.

“I’m on my way to a new one,” I said.

“Where’s that?” she asked, running purple fingernails over her tattooed left arm.

I looked through the window of her studio. “I don’t know.”

“Come on in,” she said.