Sleep

The Latest in Sleep Science

Sleep better, live better.

Posted August 29, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Sleep deprivation is common and harmful.

- New evidence suggests that poor sleep is associated with selfish behavior.

- Many popular sleep aids have no proven benefit.

- Melatonin supplements may help some sleep-deprived people, especially those in certain professions.

Goodnight room, goodnight moon, goodnight cow jumping over the moon.

So goes a ritual played out in bedrooms across the land.

The soothing repetition of Goodnight Moon and similar verses are employed by millions of parents each night as they send their kids off to dreamland. Many moms and dads practically obsess about the timing, ritual, and quality of their children’s sleep.

Why? Well, because, as everyone knows, sleep matters. Children with irregular rest routines are irritable, transformed from adorable puddle jumpers into barely bearable brats.

This parental common sense is also backed by strong science. Rats that don’t sleep don’t just become brats—they become dead (within four to five weeks). And the data isn’t just on rats. Studies demonstrate that sleep-deprived people have delayed reactions and difficulty concentrating, as well as impaired cognition and judgment.

This, of course, explains the rationale for sleep-deprivation interrogations. Given all this, why is it that a nation so meticulous about its children’s sleep is so careless regarding adults’ rest?

The Downsides of Sleep Deprivation

Data has consistently suggested that America is an under-slept nation. Survey data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 2017-18 estimated that over 30 percent of U.S. working adults slept six or fewer hours a night. [1] This is less than the minimum number of seven hours recommended by the CDC—and perhaps this deficit helps our collective angst and irritability.

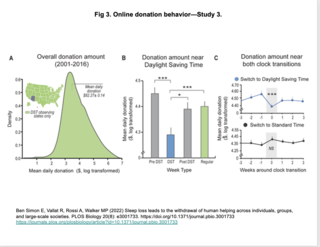

Furthermore, new evidence would seem to suggest that sleep deprivation is associated with more selfish and less altruistic tendencies. Simon and colleagues conducted a fascinating 3-tiered study just published in the journal Plos Biology presenting evidence of this link on both an individual and population level.

For example, on an individual level, sleep deprivation for a single night was associated with decreased willingness to help other people (both strangers and familiars) and decreased activation of the social cognition network on functional MRI imaging. And on a population level, from 2001 to 2016, the investigators observed a significant drop (approximately 10 percent) in the amount of online charitable donations in the week after “spring forward” daylight savings time that was not present in states that do not have daylight savings or in the week following “fall back.” [2]

Why Aren't We Getting More Sleep?

For shift workers and parents of young children, some level of sleep deprivation is virtually inevitable. But for many others, sleep deficits are preventable and should—for health, safety, and sanity reasons—be prevented.

Yet despite broad efforts to recognize sleep deprivation as a public health problem and improve American sleep hygiene, including initiatives led by NASA and the National Institutes of Health, little progress has been made. “Pushing against the wave of accelerated growth in the field has been a shoreline of indifference,” writes David F. Dinges, the Chief of the Division of Sleep and Chronobiology in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. [3]

So now that this prelude has you awake and at attention, lets’ take a less than exhausted—I mean less than exhaustive—look at best practices and what’s new with sleep research.

Recent Research in Sleep Science

The sleeping fox catches no poultry. —Benjamin Franklin

Ben Franklin, famously, required very little sleep—supposedly requiring only 30-minute-catnaps. There are certainly inborn differences in sleep requirements, but not many of us can live like Franklin. The exact physiological mechanism as to how sleep functions in a restorative manner has long been a mystery, but new evidence from mice models suggests that it may have to do with the upregulation of a “glymphatic” system that co-mingles cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid.

Lulu Xie and colleagues from the University of Rochester Medical Center proposed this mechanism for removing toxic neuro byproducts (like B-amyloid and Aβoligomers) in Science in 2013 [4]. They found that sleeping and anesthetized mice had a cortical interstitial space expansion of more than 60 percent compared to those who were awake. Thus, it may be that baseline differences in individual sleep requirements are determined by both the rate of neurotoxin creation during wakefulness as well as the degree of cortical interstitial expansion during sleep.

Regardless, we are pretty certain, for now at least, that an individual’s sleep requirement is pretty well set and not modifiable, especially in the long term. And for most of us, this requirement is at least seven hours per night.

The two best physicians of them all: Dr. Laughter and Dr. Sleep. —Gregory Dean Jr.

We might have to throw Dr. Feelgood into the mix here too. But seriously, we are just beginning to understand the physiological functions of sleep—which include encoding memories via nerve-signal repetition; increased cellular production of proteins that are likely involved in repairing damage from stress, ultraviolet light and dietary toxins; and spikes in growth-hormone release in young people. [5] These sound like beneficial functions and not ones we want to skimp on.

Do Sleep Aids Work?

So, if you are one of those looking for help with maximizing the restorative nature of sleep, what are some options?

Unfortunately, many sleep aids, while not likely to be harmful, have not had proven benefits—this being the conclusion of systemic reviews of two popular slumber supplements, white noise and valerian. [6,7] So, how about we put in a call to Dr. Melatonin from the pineal gland?

There was a time when melatonin supplementation seemed like a clever way to market a placebo to long-distance travelers. But the evidence has evolved and melatonin is now recommended by The American Academy of Sleep Medicine for daytime sleep for night shift workers with shift work disorder.

Also, in the aptly titled journal Work, consider this randomized study of refinery workers in Iran. [8] The investigators tested the effect of 3 mg of melatonin taken thirty minutes prior to sleep in 50 randomly selected workers with prior sleep difficulties as determined by two validated scales. They compared markers of sleep performance, recorded by a “Somnowatch” in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial.

Although only 39 participants finished the trial and the researchers did not utilize polysomnography (the gold standard) for assessment, they did report two statistically significant differences: melatonin administration was associated with increased sleep efficiency and decreased sleep latency versus both baseline and placebo. This study builds on prior evidence that suggests that melatonin may be a safe (low toxicity and dependency profile) and reasonably effective adjunct to regulate sleep patterns in shift workers. And there is evolving evidence to suggest that it may be helpful in other populations—such as middle-aged people suffering from insomnia (sound familiar?). [9]

The Role of Light

Light, too, can wreak havoc with sleep patterns, especially with those with off-kilter work schedules. Some commonsense approaches to mitigating the pesky effects of natural light include attempting to flip the pancake on sleep patterns.

Since melatonin production by the pineal is regulated by the light/dark cycle, it makes sense that its same effects may be achieved by carefully regulating exposure to light. Other methods noted in a detailed review article by Emens and Burgess in Sleep Med Clinics are based on physiological profiles of melatonin subjects experiencing either circadian advance or delay within 2 or 3 hours of habitual bedtime based on when they were exposed to bright light. [10] Those exposed to morning light just before the normal spike in melatonin levels before bedtime were shown to delay the circadian phase whilst those with early cycle light exposure were shown to advance the phase.

Practically, this means that shift workers should strive to manipulate their light environment as much as possible. There are vendors that sell lights that approximate natural illumination and if you go online shopping for these, look for something that provides exposure to around 10,000 lux of light and with minimal UV light. Other recommendations for the therapeutic use of natural-light-machines, as stated by the Mayo Clinic, are:

- Use within the first hour of waking up in the morning

- Use for about 20 to 30 minutes

- Keep at a distance of about 16 to 24 inches (41 to 61 centimeters) from the face

- Apply with eyes open, but not looking directly at the light

Drop, drop in our sleep, upon the heart sorrow falls, memorys pain, and to us, though against our very will, even in our own despite, comes wisdom by the awful grace of God. —Aeschylus

I'm not sure exactly what this means, although it sure sounds pretty and I think it may be referencing the germination of inspiration. Guess I’ll try sleeping on it.

References

1) U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, April 24). QuickStats: Percentage of Currently Employed Adults Aged ≥18 Years Who Reported an Average of ≤6 Hours of Sleep per 24-Hour Period, by Employment Category — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008–2009 and 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:504.

2) Ben Simon, E., Vallat, R., Rossi, A. and Walker, M.P., 2022. Sleep loss leads to the withdrawal of human helping across individuals, groups, and large-scale societies. PLoS biology, 20(8), p.e3001733.

3) Worley, Susan L. The extraordinary importance of sleep: the detrimental effects of inadequate sleep on health and public safety drive an explosion of sleep research. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 43.12 (2018): 758.

4) Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. science. 2013;342(6156):373-377.

5) Eugene AR, Masiak J. The neuroprotective aspects of sleep. MEDtube science. 2015;3(1):35.

6) Riedy, Samantha M., et al. Noise as a sleep aid: A systematic review."Sleep Medicine Reviews 55 (2021): 101385.

7) Taibi, Diana M., et al. A systematic review of valerian as a sleep aid: safe but not effective. Sleep medicine reviews 11.3 (2007): 209-230.

8) Sadeghniiat-Haghighi, Khosro, et al. Melatonin therapy in shift workers with difficulty falling asleep: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover field study. Work 55.1 (2016): 225-230.

9) Xu, Huajun, et al. Efficacy of melatonin for sleep disturbance in middle-aged primary insomnia: a double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Sleep Medicine 76 (2020): 113-119.

10) Emens JS, Burgess HJ. Effect of light and melatonin and other melatonin receptor agonists on human circadian physiology. Sleep medicine clinics. 2015;10(4):435-453.