“If you’re a black player who is a great penalty taker, like Ivan Toney, it will be on your mind,” Rio Ferdinand says as he anticipates the anxiety that may ripple through the England squad which flies to Qatar for the World Cup next week. “If Toney gets in the squad one of his first actions in the World Cup could be being brought on to take a penalty. There’s no doubt in my mind he’ll be thinking: ‘Shit, I know what happened to [Bukayo] Saka, [Jadon] Sancho and [Marcus] Rashford.’”

Those young black footballers missed penalties in the shootout that secured Italy’s victory over England in the final of the European Championship last year. They suffered sustained racial abuse online in a depressing example of the way in which prejudice is still rife. Ferdinand, who won 81 caps for England and played in two World Cups, has spent the last few years immersed in making a trilogy of films. Two documentaries about racism and sexuality consider how to overcome the bigotry that scars football while the third explores the consequences for mental health in a game which Ferdinand believes has reached a tipping point.

The World Cup will feature heavily on social media’s febrile platforms and Ferdinand knows that more hate and prejudice are likely. “That’s why the rules need to be changed to allow players to feel there aren’t repercussions from a racial standpoint if they fail, or make a mistake,” he says. “But at the moment the laws aren’t in place to protect players. So I definitely think that will be in the back of players’ minds going into high-pressure World Cup situations. It’s not just England. All players of colour around the world will be thinking that.”

An online safety bill could take another two years to be ratified. In the meantime, as Ferdinand reiterates, social media companies have the means to block and expose racist and homophobic abuse. “The problem is that they rely on toxic behaviour and hate speech so they won’t quash that element,” he says. “Racism and all forms of discrimination are welcomed on social media because that interaction equals more advertising money. We saw with Covid that if a message needs putting out on social media there are algorithms and technology for these companies to make a difference. But they can’t tackle discrimination. So it shows there is no real intention to change. We spoke to [the social media giants] but you get wishy-washy feedback: ‘Yeah, we’re trying all we can.’ No, you’re not.”

In a powerful section of his documentary on racism, Ferdinand meets technology experts at a data company called Signify and they show him how easy it is to trace abusive messages and to identify the people responsible for those postings. They are even able to pinpoint where such racists live and work. Ferdinand shared some of their findings with the Football Policing Unit and, so far, 12 cases of racist hate crime are being investigated.

Signify also suggests that 50% of online racial abuse relating to football is aimed at three players: Raheem Sterling, Wilfried Zaha and Adebayo Akinfenwa, who retired in May. Ferdinand meets Zaha and Akinfenwa and they agree to join a WhatsApp group of socially conscious footballers he formed with Romelu Lukaku. Ferdinand is emphatic that, as shown by the ability of NBA stars such as LeBron James and Chris Paul to confront racism in the US, the real power lies with current players who have the fame and social media followings to force governing bodies to take action.

“More than just highlighting the issues again we wanted to make a solution-based documentary,” Ferdinand says. “I’m not stupid enough to think a documentary is going to end these issues. But the fact we’ve been in parliament lobbying and we’re now going to board meetings at the Premier League means we’re at those decision-making tables, bringing current players and ex-players together to talk.”

Ferdinand meets Richard Masters, the Premier League’s chief executive, to stress that occasional campaigns and statements of support are not enough to combat bigotry in football. “By the time the documentaries are available I will have been at a Premier League board meeting to discuss these issues. The ball’s rolling now but it’s not about me. I want to kick that door open and say ‘come on’ to the current players because they know the problems. They’re living and breathing them every day. So they need to be heard.”

Does Masters share Ferdinand’s desire to involve current players in the battle against racism? “The fact that he’s invited me to the board meeting is a step in the right direction. But he needs to prove himself. Far too often we’ve had people in these positions engage in tokenism and box-ticking exercises. I hope he and the Premier League are true to their word.”

Ferdinand is in close communication about racism with “over 50 current players from around Europe and England. We are going to the stakeholders within the game to discuss meaningful action”.

Sexuality is an area in which Ferdinand is less familiar when campaigning against prejudice. He should be commended, however, for facing up to his own past homophobia. In the second documentary he visits his sister, Remi, who is gay, and he plays her an audio clip in which he is heard using homophobic language during a 2006 interview with Chris Moyles. A reminder of that embarrassing behaviour had been sent to Ferdinand when, on Twitter, he asked why no Premier League footballer has ever come out as gay.

“That [interview] was done so long ago and culture and language is very different now,” he says. “Yes, it was an awkward scene to shoot but my sister obviously knows how genuine I am around sexuality. She recognises the strides I’ve made since she told me and my brother, Anton, and our dad, how hard she found it to hear some of the language used when we were growing up. So it was difficult for me to admit it but that vulnerability probably makes other people think: ‘That was me as well.’ It shows a way out to the other side [of homophobia] as long as you educate yourself and have empathy.”

In another revealing moment Ferdinand asks whether it is acceptable to participate in “banter”, which borders on homophobia, in straight company. He quickly shuts down the suggestion as totally unacceptable. “It’s mad to even ask,” he says now. “If you asked the same question to do with race, you know it’s not right. Flip it to sexuality and why is it different? So for me this is definitely a learning experience.”

As part of that education process Ferdinand meets gay footballers at grassroots level, including players for Stonewall FC, as well as Collin Martin, in America, and Josh Cavallo in Australia. Alongside Jake Daniels, the teenager on Blackpool’s books, Martin and Cavallo are among the very few openly gay professionals currently playing in men’s football. Two years ago Landon Donovan, the former US international who manages San Diego Loyal, led his team off the pitch after Martin had been subjected to a homophobic slur. Ferdinand contrasts the praise Donovan received for standing up to prejudice with the fate of Darren Wildman, the academy head at Skelmersdale United in the Northern Premier League.

“Darren was at the low end of the pyramid as a coach and one of his players was abused about his sexuality. Homophobic words were said and Darren took his players off the pitch. He reported it to the referee but the other team wasn’t happy and all of a sudden his life changed because he was getting abuse. The FA then made him feel like he was the perpetrator when he was actually trying to protect his team and an individual player. He got banned and fined for abandoning the game. It’s unbelievable. When we saw him he was like a broken man.”

after newsletter promotion

Wildman was told on Twitter that he should have been “gassed like the Jews” as antisemitism merged with homophobia.

“Look at Landon Donovan who was put up in lights, rightly so, for the way he handled the same situation,” Ferdinand says. “It was amazing to see his team walk off the pitch – but such a difference to what happened here.”

What advice would Ferdinand offer if a gay Premier League footballer told him privately he was considering coming out? “I would say it very much depends on the network of people around you. A strong core of people can alleviate some of the pressure. It’s going to be difficult, and hard, but the experiences [of coming out] I’ve heard are very positive. I would say you will gain a lot but be prepared for it to be tough.”

It’s obvious why there are so many mental health issues surrounding football – particularly among young players released by professional academies. Eighty per cent of those discarded players develop depression and Ferdinand explains that of the 1.5 million boys who play representative youth football in England, only 180 make it to the Premier League. He describes the 0.012% rate as “crazy” and acknowledges the struggle his two teenage sons, who are at Brighton’s academy, face in their quest to play elite level football.

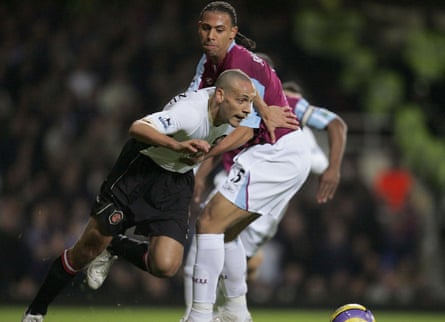

Ferdinand also meets some of his former West Ham academy teammates who were not lucky enough to match his success. “Lee Boylan is the one that stands out for me,” the 44-year-old says. “He played in the same team at West Ham as me and Frank Lampard. He was our top goalscorer in a youth team that won the league two years on the bounce. In the small town in Essex where he grew up he was a mini-superstar. But Lee didn’t make the first team at West Ham. He slips into depression, with massive anxiety, and breaks down. He never really recovers and you can see he’s still really scarred from that experience.”

Ferdinand invites all the leading academies to a forum to discuss how to deal with mental health problems among young players and he is disappointed when only four clubs attend. “They are very guarded around the media. But the subject matter should have overridden all of that.”

Each one of Ferdinand’s three documentaries faced the same problem. Whether trying to get footballers, their agents or clubs to discuss racism, sexuality and mental health, even a former player as famous as Ferdinand struggled to engender open conversations. “Trying to penetrate the ecosystem of football was so difficult. Even with my background in football, you could still see doors closing and people unwilling to talk. Agents getting in the way or players not wanting to talk because they have been on the receiving end of these issues. I was thinking; ‘What the hell? Why would you not want to be part of a process that is not just about highlighting the issue but trying to find solutions?’

“Zaha, Lukaku and Akinfenwa have had so much prejudice thrown at them. But they listened and asked good questions. As soon as they heard we were looking for solutions they wanted to be part of it. But there weren’t enough brave people like that.”

Rio Ferdinand’s Tipping Point is available on Prime Video on Friday 11 November