In 1981, David “Syd” Lawrence played his debut season for Gloucestershire – a big deal for a 17-year-old, who had inherited his cricketing passion from his Jamaican father. He was sitting in his hotel room during his first away game when there was a knock at the door. He opened it to find a banana skin outside, left there by one of his own teammates. “And I just remember shutting the door…” says Lawrence.

That’s all the former England bowler manages, for a long while. The pain of the memory has sandbagged him, and he needs time to recover. “I’m sorry,” he says eventually. “It’s hard when you relive this.”

Lawrence has rarely spoken of experiences like these. “You didn’t have anywhere to go back in those days. There’s no one you can turn to. And if you did, everyone was so keen to say you’re a difficult person or you’ve got a chip on your shoulder, you just think it’s not worth it.

“I just sat in that room thinking: I’m a cricketer, what makes me different? Why would somebody want to do that, just because of the colour of my skin?”

Seven years after that incident, Lawrence became the sixth black cricketer to play for England. There have been only 21 in total, and few of those who experienced racism have spoken openly about it. “Occasionally me, Syd and Chris Lewis might talk about these things between us,” says Phil DeFreitas, “but while you were playing for England your concern was staying in the side. You didn’t want to be seen as a troublemaker.”

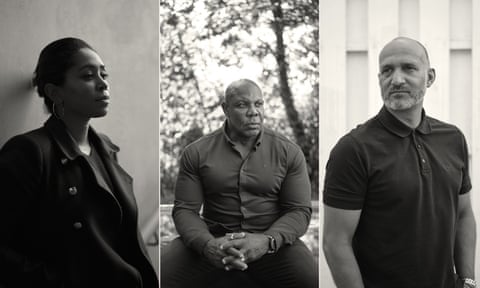

Two new projects are honouring the achievements of the black cricketers who have played for England, exactly 40 years after Roland Butcher became the first. Photographer Tom Shaw is completing a series of portraits of the players that will hang in the museum at Lord’s; and a Sky Sports documentary, You Guys Are History, is airing during the Oval Test. While there is plenty to celebrate from their careers – from Norman Cowans bowling England to victory in one of the greatest Ashes Tests of all time, to Jofra Archer’s World Cup-winning super over – the moment has emerged when the players finally feel able to open up about their struggles.

“To be honest, it’s a relief to be able to start talking and letting people know what you went through and how you felt,” says DeFreitas, of his own 44-Test career. “I never felt I could trust anyone, and whenever I did it backfired on me – you’d find that what you’d talked about had been used against you. So when I went through tough times I just held it in.”

Even when DeFreitas received letters from the National Front, sent to him when he was playing for Lancashire and then Derbyshire in the 1990s, he was afraid to tell the England management. “Can you imagine what it’s like trying to run into bowl for England with all that going on in your head? You don’t perform as well, and then you get crucified in the media.

“People make judgements on your performances but no one knew what we were going through. All my life has just been about fighting, trying to prove people wrong.”

Lawrence’s resistance to the racism he encountered turned him into one of his era’s meanest fast bowlers before injury cut short his Test career. “What I did was got in the gym and made myself a lot bigger and stronger, so nobody could ever mess with me again. That’s the way I dealt with it.”

For Mark Butcher, interviewing the players for the Sky documentary was a revelation. He admits he had had “zero” conversations about the experience of being a black England cricketer before, “which is why there were certain parts where I was stunned into silence at some of the stuff they’ve told me”.

As someone whose father was a professional player and then coach at Surrey, his own path to the elite level of the game was a far smoother one. “Growing up at the Oval, everybody knew who I was before I knew who I was. So my journey was very different from other guys born of first- or second-generation immigrants, or people born outside the country.”

Players in the documentary offer a range of different opinions on how perceptions of race have affected their careers. Dean Headley, whose father Ron and grandfather George were both Test cricketers, says he never suffered because of his skin colour. Chris Lewis, meanwhile, has become very aware of the labels he laboured under – stupid, lazy – and even Chris Jordan and Jofra Archer, two of England’s current stars, have been the subject of racist abuse on social media.

When Mark Alleyne speaks about the lack of black coaches in England today, it’s impossible to avoid the feeling that structural racism is still hampering careers. Having led his county to numerous trophies, Alleyne got his coaching qualifications – yet after seven years of experience working with MCC Young Cricketers at Lord’s he could still only score a single job interview, for the England women’s team. Black coaches in cricket have not enjoyed the same respect as, say, Australians, who often arrive in the UK with good reputations irrespective of what they’ve achieved.

“When people see black coaches they don’t necessarily see them as high-performance people,” says Alleyne. “We need to change that lens.” Lawrence, who became a certified personal trainer after retirement, says he wrote to 15 counties offering his services as a strength and conditioning coach at a time when cricket was just starting to realise their worth.

“But they don’t take you seriously. I’d successfully competed in bodybuilding for years, I told them about my experience with fitness, training and nutrition, and no one was interested – most didn’t even reply. You think, OK, why’s that? You don’t know and so you give up.”

Butcher says it was only making the documentary that made him realise how steep a decline there had been in black representation in the sport. “In the 2000s, it felt like there were black players all over the place – people like me, Alex Tudor, Michael Carberry – and you assumed that would continue. You didn’t notice that the numbers were starting to plummet.” There’s been a 75% decline in the number of black British professional players since that peak; and in the recreational game black players account for less than 1%.

Cricket has been supplanted in the Caribbean-heritage communities that once worshipped it, mostly by football, a sport that’s both more popular and more affordable to play (Alleyne’s own son, Max, has just signed a contract with Manchester City). “I loved cricket because my mum and dad loved it, and the West Indies players were always talked about in my house,” says DeFreitas. “Do those families talk about cricket now, or will they be talking about Arsenal, Liverpool, Tottenham?”

The Oval used to be a heartland for black cricket-lovers, drawn from south London’s immigrant communities. The demographic of spectators at this week’s Test match reflected little of that legacy. Ebony Rainford-Brent, the first black woman to play cricket for England, points out that until recently, re-engaging the black community wasn’t even on Surrey’s agenda, let alone the England and Wales Cricket Board’s.

“This is why we need more representation at board levels,” says Rainford-Brent, who became Surrey’s director of women’s cricket in 2015. “It wasn’t on the radar because we’ve had no black leaders in our game, no one in positions of influence and none coming through because of the way it’s structured.

“But as soon as I brought it up, our CEO said we need to do something. And once you raise it, you can move quickly and make change.” The ACE programme, a talent pathway for black cricketers funded by Surrey, already has 65 young players in its academy, several of whom have now had trials for representative cricket. “What we found was as soon as we offered the opportunities people grabbed it.”

Having grown up in south London, Rainford-Brent is acutely aware of the barriers that keep young people encountering or progressing in the sport. “If it wasn’t for a particular woman who spotted me at a tournament and did everything she could to help me and get me scholarships, I wouldn’t have had my career. We have a really good system that works for a certain type of person, but we haven’t created the system that works for diverse, lower socioeconomic backgrounds and if you’re in the inner city, if you’re not in private schools, there’s just a void.

“Even if you’re in the performance structure your chances of making it vary hugely. And it’s not just the black community suffering.” If England hopes to build on the legacy of its 21 black cricketers, it could do worse than listening to what they have to say.