After Sarah Hale became the first female magazine editor in America, she used her unique platform to help create Thanksgiving as we know it.

James Reid Lambdin/Richard’s Free LibraryAn 1831 portrait of Sarah Hale as a young widow.

Before Sarah Josepha Hale began her crusade to make Thanksgiving a national holiday, the day was mainly celebrated only in New England, where each state set its own date. Some states held Thanksgiving as early as October or as late as January while the holiday was virtually unknown in Southern states.

But in 1827, Sarah Hale published her first novel, Northwood. “We have too few holidays,” Hale wrote. “Thanksgiving like the Fourth of July should be a national festival observed by all the people.”

Thanksgiving, Hale believed, taught Americans about their “republican institutions.” And so Hale began working on her lifelong goal of promoting Thanksgiving as a national holiday.

As one of the only women editors in the country, Hale had a unique ability to influence American culture. In Godey’s Lady’s Book, Hale published editorials urging Americans to celebrate Thanksgiving. She published poems celebrating the Thanksgiving feast and recipes for roast turkey and pumpkin pie.

It took several decades, but in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln finally proclaimed “a Day of Thanksgiving and Praise” — all because of a letter from Sarah Josepha Hale. So how did Hale succeed in turning Thanksgiving into a national holiday — and why have most Americans forgotten her?

Sarah Josepha Hale’s Early Life And The Origins Of “Mary Had A Little Lamb”

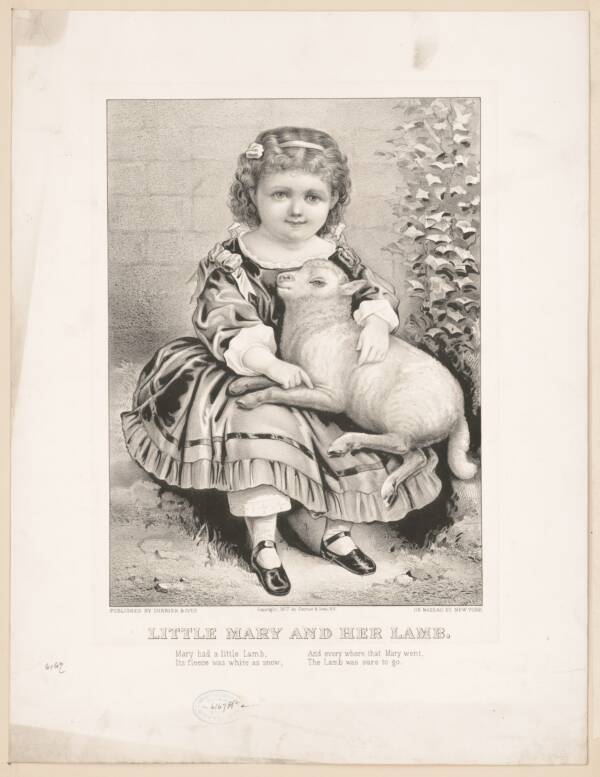

Popular Graphic Arts/Library of CongressAn 1877 illustration of “Little Mary and her Lamb.”

Born in 1788 on a remote New Hampshire Farm, Hale learned to read at her mother’s knee. Later, her brother Horatio, who studied at Dartmouth, tutored the girl.

Next, Sarah Josepha was a schoolteacher for several years before she married David Hale, a lawyer who also encouraged his wife’s educational ambitions. But tragically before their 10th wedding anniversary, David died.

Now widowed, Hale had to support five young children and her education came in handy. She began publishing poems, including a book called Poems for Our Children.

That volume included a poem titled “Mary’s Lamb.” The nursery rhyme became an instant hit, inspiring composer Lowell Mason to turn it into a song.

In Hale’s original text, the poem “Mary’s Lamb” read, “Mary had a little lamb,/ Its fleece was white as snow,/ And every where that Mary went/ The lamb was sure to go;/ He followed her to school one day/ That was against the rule,/ It made the children laugh and play,/ To see a lamb at school.”

The hit poem appeared in McGuffey’s Reader, which educated generations of children. However, the reader published the poem without crediting Hale.

Writing helped Hale support her family. In 1837, she became editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. As an editor, Hale encouraged women to submit original material and paid her authors well. The magazine, Hale hoped, would promote “the moral and intellectual excellence” of women.

Hale’s Record Of Activism

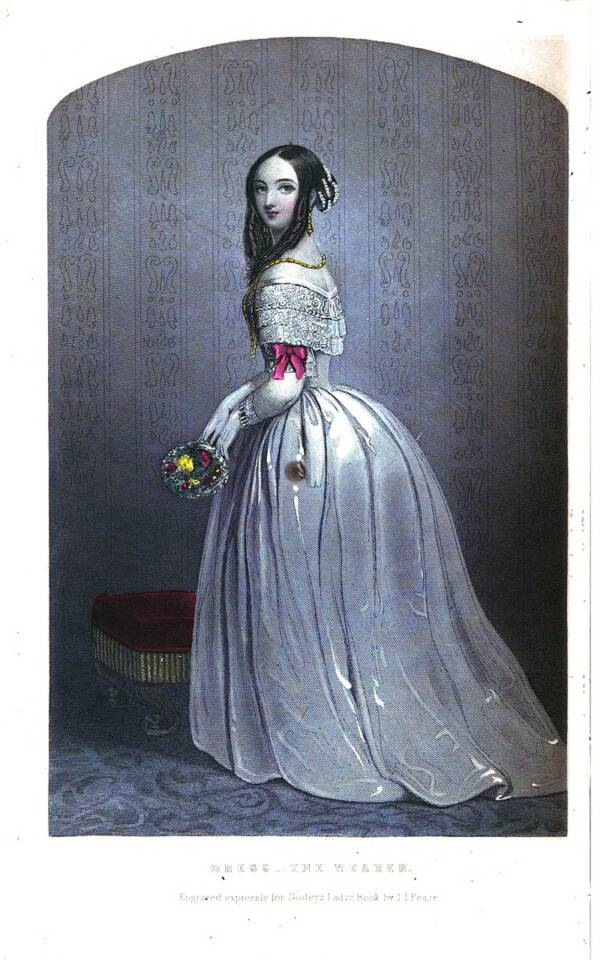

Joseph Ives Pease/Wikimedia CommonsAn 1851 fashion plate from Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Godey’s Lady’s Book became highly influential in 19th-century America and was a favorite publication among middle-class women. Like many modern women’s magazines, Hale’s publication encouraged brides to don white dresses and recommended wrinkle treatments. But she didn’t stop there.

Sarah Hale also used her magazine to promote specific causes. She believed strongly in women’s education and encouraged mothers to teach their daughters alongside their sons. Additionally, the magazine argued for the abolition of slavery in the years before the Civil War.

Hale’s activism extended beyond the magazine. Committed to preserving history, Sarah Hale raised money to maintain historic sites, including George Washington’s Mount Vernon home.

When the Bunker Hill Monument in Massachusetts ran short on funds, Hale stepped in. Using her magazine and a local network of women in Boston, Hale raised more than $40,000 through donations and the Bunker Hill Monument Fair. Against the objection of men who implied that women were stealing from their households by making donations, Hale and other women activists transformed the monument into a reality.

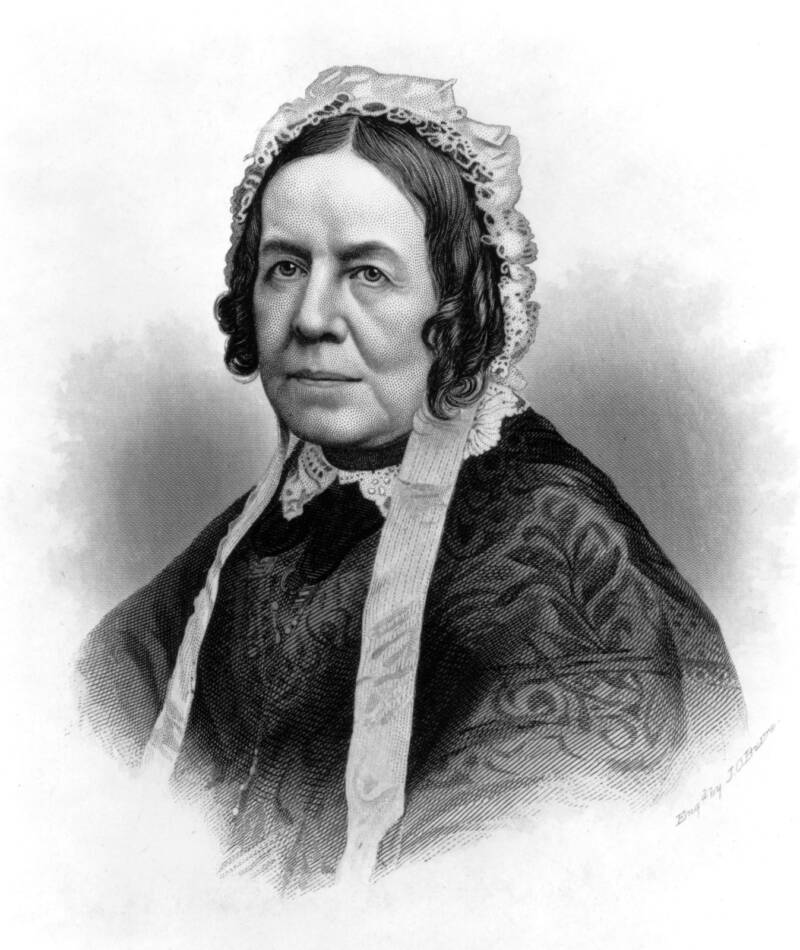

W.B. Chambers/Wikimedia CommonsAn engraving of Sarah Josepha Hale from 1850.

A common theme united Hale’s activism: she wanted to improve her country and promote patriotism. Hale’s decades-long commitment to the Thanksgiving holiday was part of that larger goal.

How The Civil War Made Thanksgiving A More Urgent Cause For Sarah Hale

Sarah Josepha Hale wanted Thanksgiving to become a unifying holiday that celebrated peace. Ironically, her campaign might have failed without the Civil War.

Starting in 1846, Hale tirelessly advocated for a Thanksgiving holiday and encouraged her readers to write to their representatives. But some politicians were not receptive to Hale’s activism. President Zachary Taylor threw up his hands in 1849 and said each state could set its own Thanksgiving day. Others argued that Thanksgiving violated the separation of church and state.

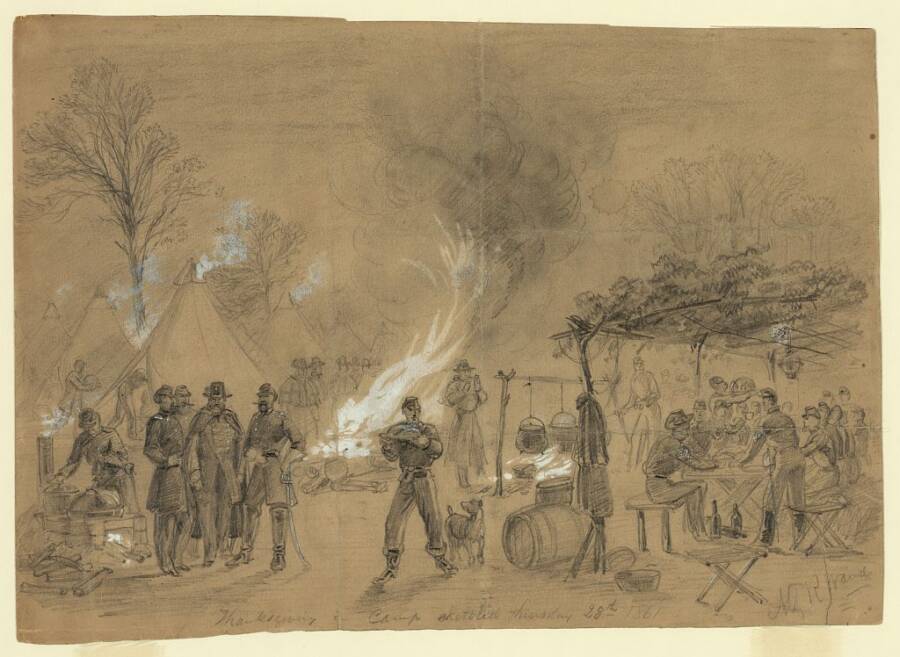

Library of CongressUnion soldiers celebrating Thanksgiving in Nov. 1861.

Southerners rejected the holiday as another Northern imposition. In Virginia, Governor Henry Wise scoffed that he refused to acknowledge the “theatrical national claptrap that is Thanksgiving.”

The holiday was personal to Sarah Hale. As a New Englander, Hale regularly celebrated Thanksgiving with her family. In Northwood, her 1827 novel, Hale devoted a full chapter to the holiday. She also saw Thanksgiving as an opportunity to bring Americans together in a time of increasing polarization.

When war broke out between North and South, Hale saw Thanksgiving as more important than ever. In an editorial, she encouraged readers to “put aside sectional feelings and local incidents” to celebrate Thanksgiving.

Instead, the holiday became even more divided. In 1861, Jefferson Davis proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving after a Confederate victory. The next year, the Confederate President issued a similar proclamation.

The Union states celebrated their own Thanksgiving in 1862 after the April Battle of Shiloh and in 1863 after the July Battle of Gettysburg.

Hale’s 1863 Letter That Persuaded Abraham Lincoln To Make Thanksgiving A National Holiday

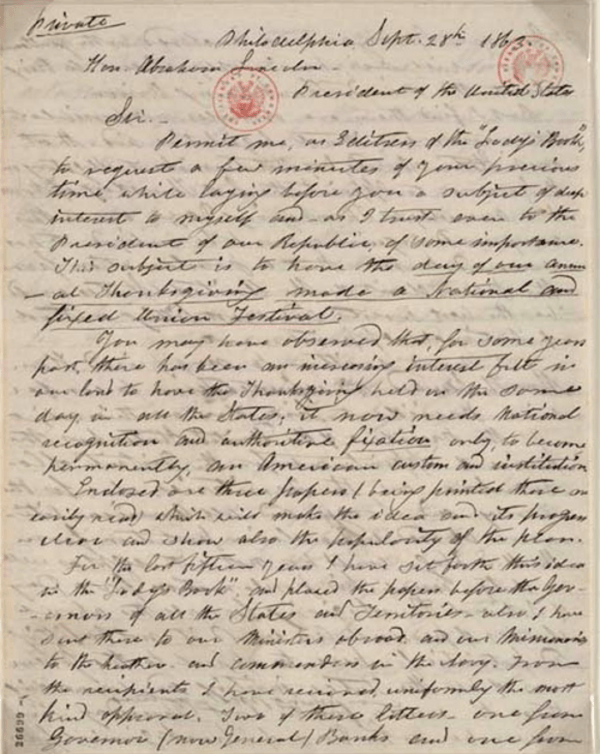

Sarah Josepha Hale/Library of CongressThe Sept. 1863 letter that Sarah Josepha Hale sent to President Abraham Lincoln.

In September 1863, President Abraham Lincoln was busy leading the Union in a war against Confederate traitors. But when Sarah Josepha Hale sent a personal letter to the president, Lincoln listened.

The letter, dated Sept. 28, 1863, encouraged Lincoln to make an “immediate proclamation” recognizing Thanksgiving as a national holiday. With the president’s help, Hale hoped, Thanksgiving could become a permanent “American custom and institution.”

Hale openly linked the holiday with the war effort, calling it “fitting and patriotic” to hold Thanksgiving as a “great Union Festival of America.” The editor encouraged Lincoln to choose the last Thursday in November for the holiday in memory of George Washington’s 1789 day of Thanksgiving.

Since Nov. 26, 1863 was less than two months away, Hale gently suggested “an immediate proclamation would be necessary.”

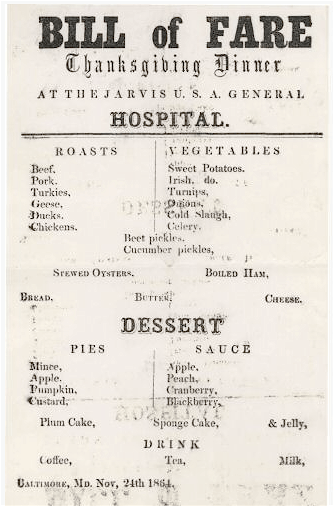

Unknown/Wikimedia CommonsThe menu at the Jarvis U.S.A. General Hospital for Thanksgiving 1864.

Sarah Hale’s dream of a unifying Thanksgiving looked farther out of reach than ever. Lincoln had just declared a day of Thanksgiving in Aug. 1863 for Gettysburg. It seemed a long shot to ask the president to declare a national Thanksgiving holiday a few months later.

Would Hale’s gamble of writing to Lincoln pay off? Perhaps aware of overstepping her bounds, Hale ended her letter to Lincoln by writing, “Excuse the liberty I have taken.”

Less than a week after receiving Hale’s letter, Lincoln issued the proclamation Hale recommended. In his Oct. 3, 1863 proclamation, the president explained, “in the midst of a civil war of unequalled magnitude and severity, the American people should take some time for gratitude.” As Hale recommended, Lincoln set the last Thursday in November as Thanksgiving day.

Why Don’t We Commemorate Sarah Josepha Hale Today?

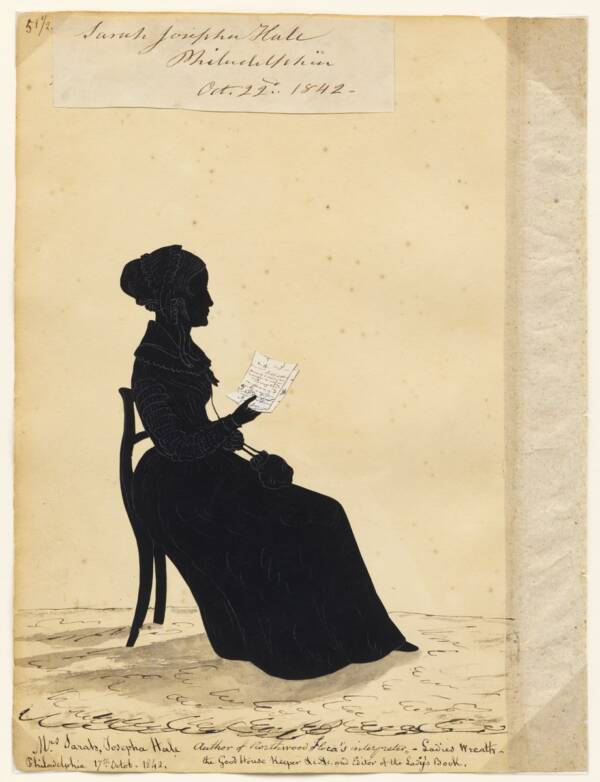

Auguste Edouart/National Portrait GalleryA silhouette of Sarah Hale, shown holding the letter she sent to Lincoln about Thanksgiving.

Today, Thanksgiving is one of the most popular holidays in the U.S. So why don’t we remember Sarah Josepha Hale?

Hale was an important voice in 19th-century America, but she believed in the “secret, silent influence of women.” Although she promoted women’s education and argued for women’s employment, Hale did not think women should take a prominent role in public life. In fact, she was against giving women the right to vote.

Hale retired in 1877, the same year that Thomas Edison recorded speech for the very first time — reciting the first lines of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” into his newly-invented phonograph. Hale died at her Philadelphia home two years later at 90 years of age.

Library of CongressThough she had a successful career in a male-dominated industry, Sarah Hale didn’t consider herself a feminist.

Thanksgiving should be a unifying, patriotic holiday, according to Hale. Because of her views, Hale was likely happy to let Lincoln take public credit for the national holiday while she secretly influenced him behind the scenes.

And Thanksgiving wasn’t the only holiday Hale shaped. She also popularized indoor Christmas trees, ensuring that her quiet influence would be felt in American homes for more than a century after her death — and most likely for centuries to come.

After this look at Sarah Hale, learn how other countries celebrate Thanksgiving and then check out these weird vintage Thanksgiving ads.