Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Paleontology

Paleontology

Educating “Professor Dave” on the Fossil Record and Genetics

I have been responding to a video by popular YouTuber “Professor Dave” aka Dave Farina. As readers will have noted, Mr. Farina’s attack (Farina 2022) on Stephen Meyer and Darwin’s Doubt is quite scattershot and disorganized. My debunking follows his video minute by minute and so is necessarily meandering. This is the sixth post in my series. See my earlier posts here, here, here, here, and here. I have inserted timecodes in square brackets throughout.

[TC 44:25] Now, Farina addresses birds and acknowledges Archaeopteryx as the oldest bird from the Late Jurassic. He says that Xiaotingia, Anchiornis, and Aurornis predate Archaeopteryx and show evidence of feathers. I elaborated on the various problems with Xiaotingia, Anchiornis, Aurornis and other feathered dinosaurs in a recent article (Bechly 2022f), which shows that none of them solves the temporal paradox of early birds. Fossils like Xiaotingia also fail to contribute to the issue of feather evolution, as long as their phylogenetic attribution is in a state of chaos.

In its original description (Xu et al. 2011) Xiotingia was considered as closer relative of birds than Archaeopteryx, which was transferred to dromaeosaurid dinosaurs, better known as raptors. Shortly after, another study found Archaeopteryx closer to birds (Avialae) and Xiaotingia as a relative of Anchiornis within troodontid dinosaurs (Lee & Worthy 2011). An updated analysis by Senter et al. (2012) also found Archaeopteryx to be closer to birds, but found Xiaotingia as a dromaeosaurid raptor rather than related to Anchiornis in Troodontidae. A new and very comprehensive analysis of 1,500 anatomical characters by Godefroit et al. (2013) again repatriated Archaeopteryx to the bird lineage but placed Xiaotingia one branch even closer to modern birds than Archaeopteryx. One year later came a study of 853 characters by Brusatte et al. (2014), which confirmed the avian position of Archaeopteryx, but placed Xiaotingia outside of birds and again within troodontid dinosaurs. Finally, Cau (2018) placed Xiaotingia as sister group to the Scansoriopterygidae, which are of a highly controversial phylogenetic position themselves.

Things are even worse with Aurornis: Aurornis xiu, was described by Godefroit et al. (2013), who considered Aurornis as more basal and somewhat older than Archaeopteryx. But an embarrassing piece of information was hidden in the online supplementary information of this sensational Nature publication: the Aurornis fossil had not been found during the team’s excavations in China but had been acquired from a fossil trader. The authors even acknowledged that the fossil might also come from the Cretaceous Yixian locality and could be up to 35 million years younger (Balter 2013), which would of course invalidate its status as oldest bird. Luis Chiappe, one of the world’s leading experts on fossil birds, commented that the dubious origin from a trader and exquisite preservation of the fossil should raise eyebrows, and his colleague Stephen Brusatte argued that “in the case of things like Aurornis, CT scanning is essential. Without it, there will always be lingering doubt that the specimen is genuine” (Balter 2013). As Aurornis has not been CT-scanned until today, the jury is still open.

Apart from that, the abovementioned new phylogenetic study by Brusatte et al. (2014) recovered Aurornis outside of birds and placed it within troodontid dinosaurs, which agrees quite well with its wings that appear to be too short for active flight. So, even if it is a genuine fossil, Aurornis could be younger than Archaeopteryx and/or not a bird at all. The most recent study by Pei et al. (2017) suggested that Aurornis xui is most likely not a valid taxon and indeed just a synonym of Anchiornis huxleyi.

Missing the Real Problem

Anyway, the real problem is again something totally different: it is the fact that the fossil record leaves hardly any time for pennaceous feathers, which are the most complex integumental structures of vertebrates, to evolve from hair-like “dino-fuzz” of more primitive theropods. This not only involves the “temporal paradox” (Bechly 2022f) of assumed descendants being older than their assumed stem group, but more importantly involves a severe waiting time problem to accommodate the required genetic changes in the available window of time (see further on for a discussion about the waiting time problem).

Farina says that if you want to make “creationists’ head explode” you just have to mention that reptile scales and bird feathers are made of the same keratin. Oh boy, where to start with this inaccurate claim: first it’s again conflating creationism and denial of common descent with an ID inference. But Farina also gets his facts wrong: scales and feathers are not made of the “same keratin simply in different arrangements,” but feather keratin differs from other keratins (Fraser & MacRae 1959, Stettenheim 2000, Alibardi & Toni 2008, Wu et al. 2018). Also, the homology of scales and feathers has been refuted by developmental biology for some time. They are only homologous on a very deep level as originating from a similar embryonic precursor. Dhouailly (2009) therefore concluded: “Concerning feathers, they may have evolved independently of squamate scales, each originating from the hypothetical roughened beta-keratinized integument of the first sauropsids. The avian overlapping scales, which cover the feet in some bird species, may have developed later in evolution, being secondarily derived from feathers.”

Again, Mostly Wrong

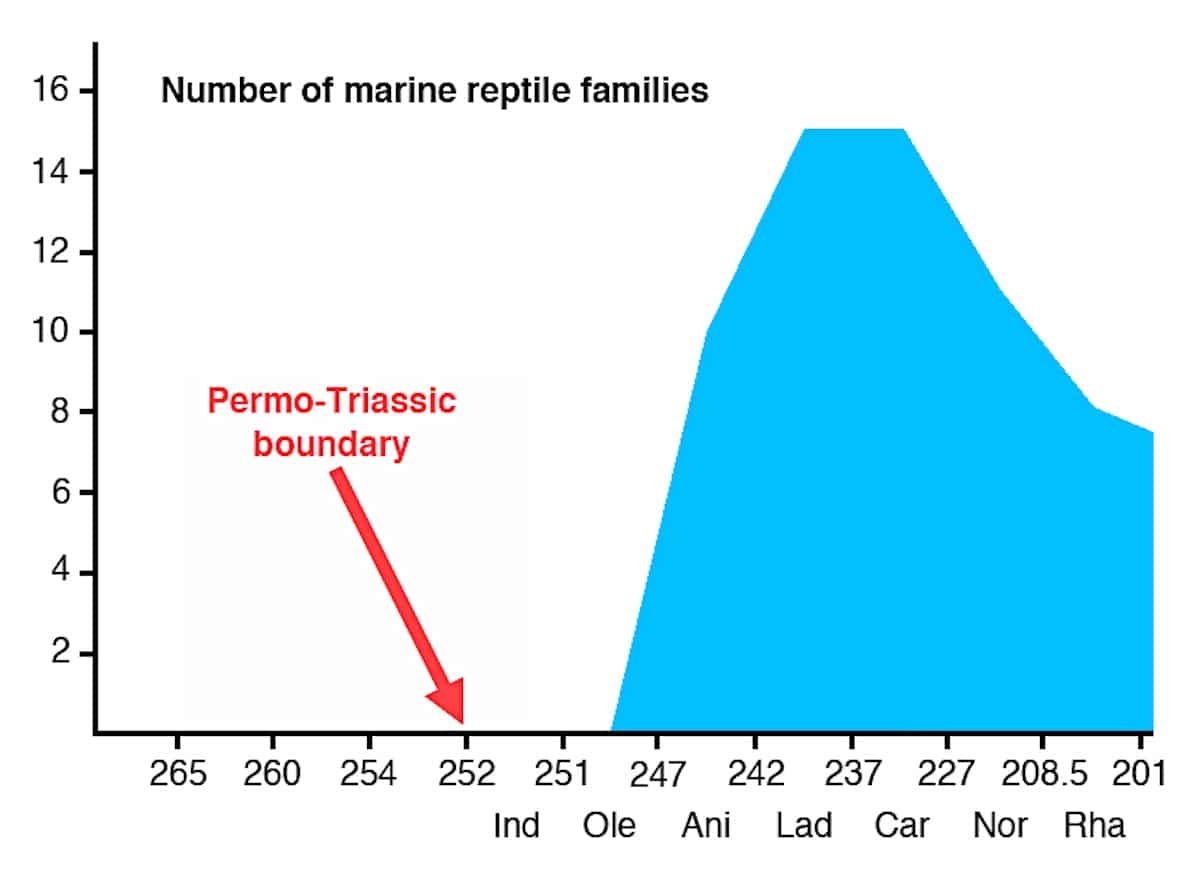

[TC 45:09] Next on his list is the issue of marine reptiles. Farina mentions three groups and claims that we have fossils documenting their evolution. This is again mostly wrong. Most of all, the real issue is the sudden jump from zero families of marine reptiles to 15 different families of marine reptiles within only 9 million years and “from obscure origins in the Early Triassic” (Twitchett & Foster 2012: fig. 5).

What about the alleged transitions? Take for example ichthyosaurs, where Farina mentions “hupehsuchus and Cartorhyncus” as alleged transitional forms with less specializations. He can hardly write the names correctly, which are Hupehsuchus and Cartorhynchus. These two taxa look very ichthyosaur-like and by no means close the gap between assumed lizard-like ancestors and fish-like ichthyosaurs. Hupehsuchia clearly were already fully marine and unable to move on land (Carroll & Zhi-Ming 1991, Chen et al. 2014a), while for Cartorhynchus it is not firmly established that they could still support themselves on the shore like sea turtles. Motani et al. (2015) only speculated that its usually large flippers “probably allowed limited terrestrial locomotion,” which was of course exaggerated and overhyped in the media reports and other comments (e.g., Dunham 2014). A new study that described Sclerocormus as the sister genus to Cartorhynchus found “that ichthyosauriforms evolved rapidly within the first one million years of their evolution” (Jiang et al. 2016). This means that the fish-like habitus of ichthyosaurs originated from terrestrial quadrupedal ancestors within a quarter of the lifespan of a single large vertebrate species. Not exactly gradual in my view! Indeed, a friend of mine, who is one of the leading experts on ichthyosaurs and not a theist, privately and confidentially told me that he came to doubt neo-Darwinism as an adequate explanation for this very reason.

An Abominable Mystery

[TC 45:46] Farina then turns to the origin of flowering plants, also known as Darwin’s abominable mystery (Buggs 2017, 2021). He diminishes this monumental problem with a puny comment about how it “has been a bit of a mystery.” He claims that recent studies of extinct clades like Bennettitales, Pentoxylales, and Gigantopteriales helped to narrow the gap between molecular clock dates and the fossil record of flowering plants. This is far from being established. Even though Bennetitiales and Pentoxylales have been supported in the so-called anthophyte hypothesis as close relatives of Gnetales and angiosperms (e.g., Doyle 2006, Soltis et al. 2008, Rothwell et al. 2009), the most recent study recovered these fossil taxa as more closely related to living gymnosperms (Shi et al. 2021).

More importantly, the original anthophyte hypothesis was thoroughly refuted by the results of modern phylogenomics, which showed that Gnetales are more closely related to conifers than to flowering plants, so that similarities between Bennetitales and angiosperms could also be parallelisms (Donoghue & Doyle 2000, Ran et al. 2018). Gigantopteridales (Gigantopteriales is a misspelling) have rarely been considered as relatives of angiosperms and I suppose that Farina either confused them with Glossopteridales or relied on dubious sources in Wikipedia. Soltis (2017) reviewed the problematic position of the various fossil taxa and concluded that “Pentoxylales, like Bennettitales, have been envisioned as part of a separate lineage, perhaps sharing a common glossopterid ancestor with angiosperms, but not as a close relative or direct ancestor of the angiosperms.”

I have written extensively about the issue of Darwin’s abominable mystery and the debunking of all alleged Jurassic angiosperms (see Sokoloff et al. 2019, Bateman 2020) in a previous article series (Bechly 2021f). Therefore, just this revealing quote from the seminal paper by Bateman (2020): “Given current evidence, all supposed pre-Cretaceous angiosperms are assignable to other major clades among the gymnosperms.” Kew Garden botanist Richard Buggs recently clarified that “despite much progress in these areas, there is general agreement that Darwin’s ‘abominable mystery’ remains intact, and the origin and diversification of the angiosperms remains one of the greatest open questions of the history of life” (Buggs 2021).

[TC 46:06] But Farina has some more recent stuff to impress his gullible audience. He cites a paper by Wang (2021) about an alleged Middle Jurassic angiosperm fruit Dilcherifructus mexicana, which shows that he is uncritically quoting any kind of junk science that he can google (Yuan 2022). Anybody with a minimal knowledge of the field would have been suspicious about why such a sensational discovery, that would be akin to finding the holy grail of paleobotany, was published in a dubious journal without an impact factor instead of in a cover story in Nature. There is another reason, why this paper was totally ignored by the paleobotany scientific community. The reason is simple: the paper is simply bonkers. Here is what Mario Coiro, an expert on plant evolution commented on Twitter when asked by a colleague what he thinks Dilcherifructus is: “a Samaropsis-like winged seed. And a proof that plant anatomy is taught so poorly that a gymnosperm-like stoma is mistaken for an angiosperm-like stoma.”

[TC 46:44] Finally, Farina addresses the origin of mammals. Here he is just nitpicking about a minor lapse. Meyer, who is not a zoologist or paleontologist, simply omitted to specify in a popular video that he was not talking about mammals per se but about the origin of the placental mammal orders (crown group eutherians), when he said that the very first mammals appeared in the Eocene. Farina surely was aware of this but used the opportunity for a cheap point.

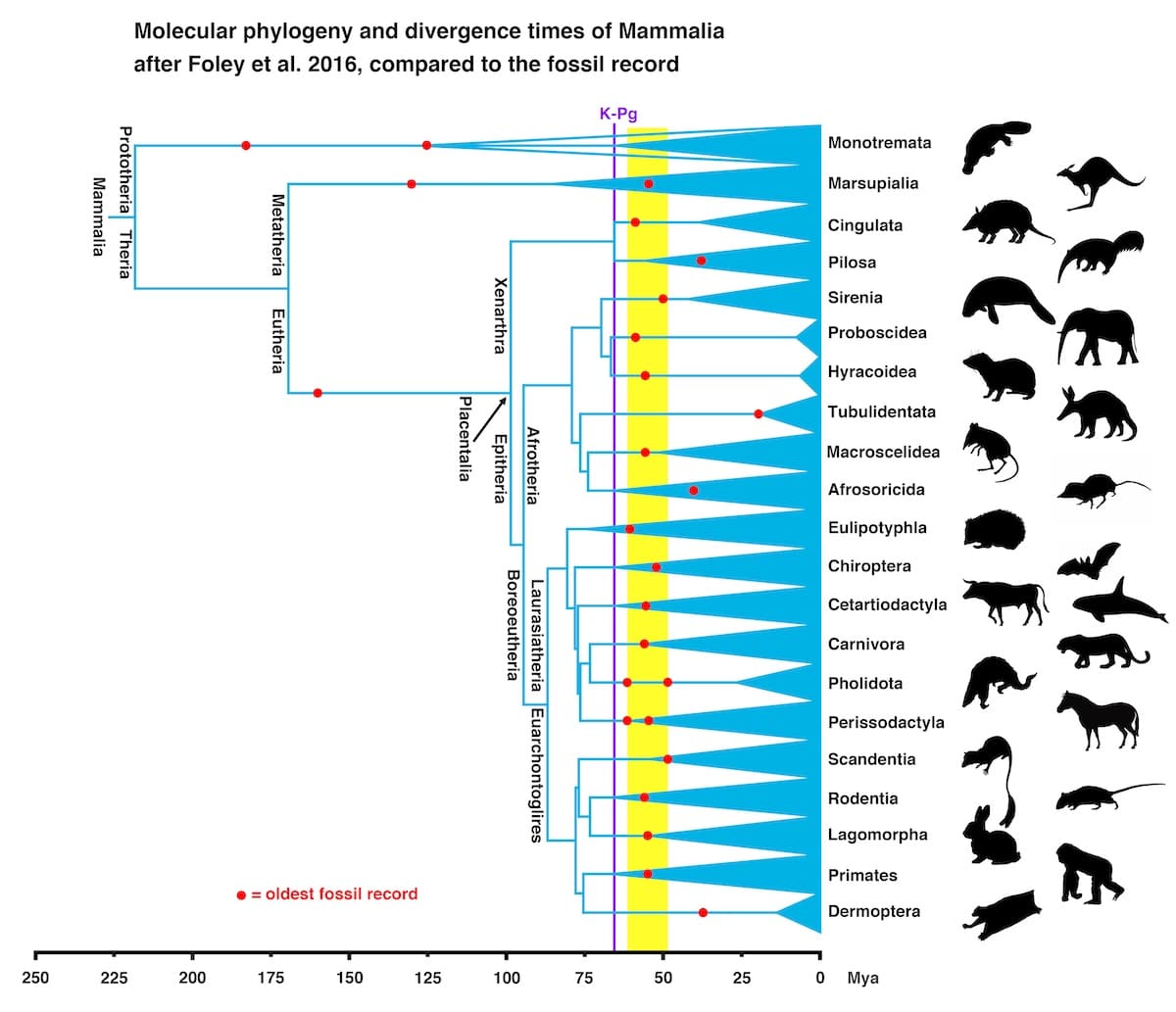

So, here is the actual problem that Farina seems ignorant about: all the orders of living placental mammals appear abruptly in a narrow window of time in the Paleogene (Lower Tertiary). There is neither fossil evidence for their gradual development, nor fossil evidence for the internal branches of the tree that would be connecting these orders. Nor is there any fossil evidence for them in the Cretaceous, where they should show up according to molecular clock studies. A recent review of the different models for the diversification of placental mammals found that “the Explosive Model is the hypothesis that is best supported by traditional interpretations of the fossil record” (Springer et al. 2019). To drive home this point, I prepared this figure, based on Foley et al. (2016: fig. 1), updated with the latest fossil data. The red dots show the oldest appearances of the mammal orders (in the window of time 62-49 mya, marked by the yellow bar), and the tree topology is based on modern phylogenomic and molecular clock studies.

[TC 47:41] Farina concludes his rant on the fossil record by repeating that Meyer is wrong on all points and lying about the absence of transitional fossils. On the contrary we have seen that Meyer is absolutely right and Farina is wrong about the science and lying about Meyer.

Moving on to Genetics

[TC 48:25] In the second section of his video, Farina moves on to genetics. This section of course contains countless red herrings and straw man fallacies, like the bizarre claim that Meyer considers information as some kind of “material substance that must be created” [TC 52:19]. You can hardly make this stuff up. As genetics is not my field of expertise, I will leave it to others to point out all of Farina’s blunders in this section. I only want to highlight a few points that caught my attention:

[TC 53:09] Farina mocks Meyer for allegedly not understanding that biology does not work by an accumulation of random changes. Well, it’s obviously Farina who does not understand the fundamentals of neo-Darwinism, which is exactly the accumulation of random changes. The fact that the accumulation is done by selection is irrelevant. It is still an accumulation of random changes. That this is or was the mainstream view and does pose severe problems for the origin of biological novelty is readily acknowledged by modern theoretical biologists (e.g., Witzany 2020) and the growing number of proponents of an extended evolutionary synthesis.

[TC 53:25] Concerning software Farina claims that “self-modifying code” exhibits a kind of evolution and refutes the ID claim that intelligent agency is required. Nothing could be further from the truth. You don’t have to believe me. Just look up what world-renowned scientist David Deutsch had to say about this (Deutsch 2011). Let this sink in:

One thing that always seems to happen with such projects is that, after they achieve their intended aim, if the ‘evolutionary’ program is allowed to run further it produces no further improvements. This is exactly what would happen if all the knowledge in the successful robot had actually come from the programmer … That is why I doubt that any ‘artificial evolution’ has ever created knowledge.

[TC 55:30] Farina says that Meyer’s frequent claim that “Mutations degrade information” does not make any sense and shows “what an unbelievable moron he is.” Let’s gloss over the vulgar insults and focus on the claim that mutations degrade information. Of course, there is good evidence for Meyer’s claim, such as computational evolution experiments revealing a net loss of genetic information despite selection (Nelson & Sanford 2013). However, instead of a long argument on the point, which you can better find in Michael Behe’s recent book, Darwin Devolves (Behe 2019), let’s see what some experts in evolutionary biology say about the creative power of mutations: “For more than half a century, it has been accepted that new genetic information is mostly derived from random error-based events [mutations]. … Meanwhile, it is recognized that errors cannot explain the evolution of genetic information, genetic novelty, and complexity” (Witzany 2020). A similar statement was made in 2016 by the famous evolutionary theoretical biologist Professor Gerd Mueller in his keynote speech for the conference “New Trends in Evolutionary Biology” at the Royal Society of London. He mentioned several explanatory deficits of the Modern Synthesis (a synonym for neo-Darwinism), meaning what the mechanism of random mutations and natural selection cannot explain. Among these deficits he listed phenotypic complexity, phenotypic novelty, and non-gradual forms of transition, basically everything that is important for macroevolution. So much for the creative power of random mutations and natural selection according to leading evolutionary biologists.

[TC 58:22] Farina ridicules Meyer for saying that “sequences that produce stable proteins are rare.” That statement is arguably defensible. But to be clear, it was said in a popular-level PragerU video, “Evolution: Bacteria to Beethoven,” obviously intended for a lay audience. From the context (Meyer discusses Douglas Axe’s research right after this intro) and from Meyer’s more technical writings it is totally clear that he was talking about the rarity of islands of function in the combinatorial search space of amino acid sequences, thus of proteins that not only fold into a stable complex three-dimensional tertiary structure, but fulfill any sophisticated biological function beyond being sticky. Farina even recognizes that this is what Meyer obviously meant [TC 59:14]. The underlying research by Douglas Axe has been published in peer-reviewed mainstream journals like the Journal of Molecular Biology (e.g., Axe 2004). Instead of addressing this main argument, though, Farina knocks down another silly straw man and triumphantly proclaims that any amino acid sequence results in a stable protein. Mr. Farina dares to call PhD molecular biologist Douglas Axe “just another DI clown” and misrepresents the argument as “Wow, big scary numbers!” [TC 1:02:18]. I leave it to Axe or others to educate Dave about the true gist of this argument, which is of course not an argument from incredulity because of big scary numbers, but a precise mathematical refutation of any possibility for a blind search process to stumble upon a new functional protein fold within the lifetime of our universe.

[TC 1:04:00] Farina mentions Richard Lenski’s long term experiment for showing how beneficial mutations created the ability to metabolize citrate in the lab. This experiment has been criticized in peer-reviewed studies (Van Hofwegen et al. 2016), which concluded that “no new genetic information (novel gene function) evolved.” It was also discussed at length by ID proponents (e.g., Behe 2020, Luskin 2021b, Witt 2021) and shown to be just another case of devolution rather than evolution.

[1:05:38] Farina claims that a modern understanding of Hox genes shows that few changes in such genes can result in dramatically different body plans. This aligns with the common claim by ID critics that no new genes and no new proteins (thus no new information) were necessary to bring about the new body plans of the bilaterian animal phyla in the Cambrian Explosion, but just a rewiring of the developmental toolkits such as GRNs and Hox genes. This is a crucial issue and indeed is a point that was raised by Charles Marshall in his critical review of Meyer’s book (Marshall 2013), based on suggestions by some researchers such as Davidson & Erwin (2006). However, new science has debunked this possibility and vindicated Meyer (also see Meyer 2013b, Bechly 2018a, 2018b, Luskin 2018, 2021a, and Coppedge 2022): the studies of Paps (2018), Paps & Holland (2018), Heger et al. (2020), and Wu & Lambert (2022) showed that thousands of new genes, far from being unnecessary for new body plans, strongly correlate with each of the animal phyla and other major transitions in the history of life.

Next, “’Crazy Stuff’? Dave Farina on the Waiting Time Problem.”