1. Introduction

Water utilities face numerous challenges related to the maintenance and modernisation of infrastructure, the ensuring of water supply and water quality, and the reduction of energy use [

1]. If the water utilities fail to adequately meet these challenges, it can result in a variety of negative outcomes including public health risks, lower levels of service, price increases, and reduced contributions to environmental and climate protection [

2]. With respect to the quality of drinking water, the presence of micropollutants has become a matter of concern over recent decades [

3,

4]. This is especially the case in areas or countries that produce their drinking water, both from groundwater and, in high percentages, from surface waters [

5]. In these cases, conventional treatment methods, which primarily aim to reduce pathogens and nutrient loads, are not sufficient to provide drinking water free from chemicals [

6] or pharmaceuticals [

4,

7]. Consequently, drinking water has to go through additional treatment steps based on, for example, active carbon nanofiltration or reverse osmosis membrane treatment, which creates additional costs. Sudhakaran et al. [

7] have reviewed different treatment methods with respect to their efficiency in reducing the micropollutant burdens of drinking water but also in light of their socio-economical aspects.

Aware of the potential negative consequences of having water utilities that fail to meet the challenges identified above, the European Commission announced in 2011 that it would adopt a legislative initiative on concessions that would include water services. As the Commission set out, service concessions were covered only by the general principles of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which limited “access by European businesses, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, to the economic opportunities offered by concession contracts” [

8]. The Commission further explained in its Communication that budgetary constraints and economic difficulties entail the need to define an adequate legal framework for facilitating public and private investment in infrastructure and services [

8]. At the time when the proposal was put forth, private companies were already involved in water services in several member states at the national, regional and local levels. For example, private water companies were involved in the provision of water services in England, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Wales [

1,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, the concessions were often awarded on the basis of public procurement law and the pertinent national laws were often different from one another in the individual member states [

12]. With the new directive, the Commission sought to provide a harmonised legal framework for awarding concessions contracts to both public authorities and economic operators [

8]. Thus, while the object of analysis is water services, the pertinent policy domain is EU single market policy and not water policy (for an overview of the latter see, e.g., [

15]).

The European Commission’s Communication resulted in strong public opposition and the launch of the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) “Water and sanitation are a human right! Water is a public good, not a commodity!”, which is better known under the abbreviation Right2Water. The last time the Commission experienced such intense public opposition was with the proposal of the Services Directive (Directive 2006/123/EC), which aimed to harmonise the rules for businesses and consumers so that they could provide or use services in the single market [

16].

Critics of the Commission’s proposal on the Concessions Directive alleged that it represented an unjustifiable extension of the single market rules to the water sector and was an attempt to liberalise water services through the back door [

17]. The criticism the Commission encountered induced it to remove the water sector temporarily from the scope of Article 12, in what would eventually become the Concessions Directive (Directive 2014/23/EU).

Pertinent research has shown how Right2Water in particular facilitated the emergence of a European public sphere [

18,

19,

20]. Studies have also elucidated the strategies adopted by the promoters of the initiative to attract the public’s attention to the issue of water and sanitation services and how they are governed [

12]. While the political process concerning the proposal and adoption of the Concessions Directive is fascinating, and reveals numerous insights into EU politics and the growing importance of civil society actors [

12,

18,

19,

20], we adopted a different analytical perspective in this study. Our research revolved around the argument that Right2Water was important for bringing the issue of water and sanitation services onto the political agenda of the EU member states [

19,

21,

22]. Therefore, we investigated Right2Water from the agenda-setting perspective [

23].

For an issue to be placed on the political agenda, supporters of the issue must draw attention to it by using appropriate strategies [

24,

25,

26]. If the promoters of an issue are members of the civil society rather than elected politicians or bureaucrats, citizens’ initiatives are a good strategy for agenda setting [

27]. Therefore, we concentrated on whether and how political parties responded to Right2Water. In the literature, the liberalisation and privatisation of water services had predominantly been investigated from the perspective of social movements (e.g., [

20,

28]). While this perspective is analytically instructive and reflects socio-political developments in modern societies, political parties, as the main intermediary actors responsible for aggregating and articulating policy preferences [

29], continue to play an important role in actual policy-making. Therefore, in our view, the analytical lens adopted here offered two advantages: first, it yielded insights into how different political parties ideologically position themselves on the issue of liberalising water services; second, it complemented studies on social movements by showing how and to what degree conventional political actors react to the demands of civil society.

Our observation period ran from 2004 to 2019, thereby enabling us to observe how attention to the issue of liberalisation and privatisation of water and sanitation services changed in response to relevant social and political events—including the ECI. Our empirical focus on Germany resulted from the particularly high levels of support for Right2Water in that country [

30].

The remainder of this article unfolds as follows. First, we provide background information on Right2Water. Then, we present our theoretical model and put forth three sets of hypotheses. In the next step, we explain our methodological approach and the data we used. Subsequently, we present and discuss our empirical findings before offering some concluding remarks.

2. The Politics of Right2Water

The ECI, as an instrument, was first introduced by the Lisbon Treaty to encourage more citizens to become involved in European policy-making. While the Lisbon Treaty went into effect in December 2009, the ECI only became operational in April 2012, after the adoption of Regulation 211/2011 and the Commission Implementing Regulation 1179/2011. A ‘successful’ ECI obliges the European Commission to decide whether to act on the issue concerned and issue the ECI a formal response. For an ECI to be successful, it must gather the support of one million EU citizens, coming from at least seven member states.

Having registered with the Commission in May 2012, Right2Water was one of the first ECIs organised. The promoters, most importantly the European Federation of Public Service Unions and various trade unions from the national civil service, collected signatures from May 2012 to November 2013. The Commission accepted the prolongation of the collection period (which must usually take no longer than one year) due to the difficulties that the organisers experienced in setting-up their online collection systems during the start-up phase of the ECI. The ECI organisers submitted the initiative to the Commission in December 2013 after receiving verification of the collected statements of support by the relevant competent authorities of the member states. Right2Water is among the few ECIs that managed to gather the necessary number of signatures [

19,

20] Since the initiative was successful, the European Commission had to respond to the organisers. The formal response was issued in March 2014 [

30].

As

Table 1 shows, public support for the ECI varied greatly across the individual member states. Member states indicated with a ratio below 1 failed to meet the minimum number of signatures. For example, Latvia was the member state with the lowest number of signatures (393) compared to the minimum number needed (6750) to meet the national quorum. We can also discern from the table that the initiative was extremely successful in Germany, where it attained 16 times the support it would have needed to meet the minimum number. The main promoter of Right2Water in Germany was the German United Services Trade Union (ver.di), but it was also supported by the German Association of Energy and Water (BDEW) and the German Association of Municipal Utilities (VKU) [

12].

Support for the initiative was also high in Austria, as well as in Belgium, Greece, Slovakia, and Slovenia. In seven more countries, Right2Water obtained more than the minimum number of signatures (Finland, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Spain, and The Netherlands), though not by a margin as high as with the aforementioned countries. In the remaining member states, the minimum number of the signatures was not reached. Among them are countries such as the United Kingdom—which comes as no surprise, considering that in England and Wales all utilities are owned privately [

1,

13].

In substantive terms, Right2Water called on the European Commission to propose legislation implementing the human right to water and sanitation as recognised by the United Nations’ General Assembly Resolution 64/292 of 2010 [

31]. A related demand concentrated on promoting the provision of water and sanitation as a public service for all [

32]. To this end, the initiative urged the Commission to:

Oblige EU institutions and the members states to ensure that all inhabitants enjoy the right to water and sanitation;

Prevent water supply and the management of water resources from becoming subject to ‘internal market rules’, and to exclude water services from liberalisation;

Encourage the EU to increase its efforts to achieve universal access to water and sanitation.

In the subsequent analysis, we concentrate on the second demand of Right2Water: the exclusion of water services from liberalisation and internal market rules. On its campaign website (

www.right2water.eu), Right2Water refers to ‘liberalisation’. However, in the public debate sparked by the initiative both ‘liberalisation’ and ‘privatisation’ were used. It should be noted that while interrelated, liberalisation and privatisation refer to two different processes. Liberalisation is the process of defining a regulatory framework for promoting competition, whereas privatisation is the process by which private organisations can contribute to the production of collective goods [

13,

33]. While we are aware that liberalisation and privatisation are different concepts, in the remainder of this study we will refer to both since this was what happened during the public debate.

There are two main considerations of our empirical focus on liberalisation and privatisation. First, the main trigger for the public’s discontent and the launch of the ECI was the Commission’s attempt to apply internal market rules to water supply and the management of water resources. Rather than the right to water or access to water and sanitation, this specific feature of Right2Water led to successful mobilisation [

12]. Liberalisation and privatisation have “gained a high level of attention—often negative—in the media, civil society and the public administration” [

13]. With respect to environmental issues and the maxim that drinking water has to be free of pollutants, the scepticism regarding the willingness of private companies to invest in further purification steps is of major concern [

3].

However, the academic literature shows that the liberalisation and privatisation of water services can also have positive effects. Lieberherr et al. [

14], for example, found that privatisation led to increased ‘dynamic’ sustainability, a term that refers to the routines that enable organisations to create and (re)combine resources to generate new strategies or change the market. Likewise, Lieberherr et al. [

34,

35,

36,

37] have shown that the involvement of private water companies in water services in Berlin, on the one hand, resulted in a lower level of resource protection and public acceptance and, on the other, in higher efficiency and profitability.

Second, our focus on liberalisation facilitated the development of the theoretical underpinning of this study, since extensive literature exists showing that political parties vary in their positions on the liberalisation of utilities [

38] as they generally hold different positions with regard to privatisation [

34,

35]. Related to that, adopting the perspective of political parties is potentially insightful since it can reveal the influence of ECIs beyond their official function as agenda-setting tools.

The massive support for Right2Water in Germany is the reason we concentrate in the subsequent analysis on how political parties in Germany reacted to the initiative. Given the high level of support for Right2Water, if we observed no reactions of political parties in Germany to this ECI, we were unlikely to observe them for any other member state. However, it should be noted that we could not afford an ‘experiment’-like analysis of the ECI’s effect on the political parties since the issue of privatising water services also became salient due to specific circumstances in Germany, such as the unravelling of the Berlin Water Company [

36]. Moreover, as the empirical analysis will show, the Commission discussed the possibility of liberalising water services before proposing the Concessions Directive. Despite these ‘contaminating’ conditions for the analysis, we will see that Right2Water had an impact of its own and was even added to the election manifestos of some parties.

3. Theoretical Considerations

The ECI seeks to generate attention for specific issues for a given period. Since an ECI, much like a regular citizens’ initiative launched at the national level [

27], places an issue on the public agenda (i.e., it defines what people talk about), we expected political actors to react to the increase in attention for the issue concerned. Of the political actors, we concentrated on political parties since they are important intermediary organisations in parliamentary systems. This is also clear from the fact that research in comparative politics has investigated how agenda setting affects the positioning of parties [

26,

36]. We expected parties to react to agenda setting in their electoral campaigns by choosing what topics to speak on (issue salience) and how (issue positioning).

Salience theory posits that parties structure their rhetoric by emphasising different topics rather than by opposing each other on the same topics, which becomes habitualised and helps voters differentiate parties [

39]. Thus, a promising strategy for political parties is to refer as much as possible to issues they are associated with (i.e., which they ‘own’ [

40]). If these issues assume importance in public debate, the parties concerned have an electoral advantage [

39]. Scholars have predicted the relevance of salience theory to numerous policy domains and to a large number of countries [

41,

42]. With regard to water policy more specifically, Schaub, for example, has shown that salience theory is relevant to the positioning of political parties, including on specific issues such as agricultural pollutants in water [

43].

Following salience theory, we expected left-wing parties that generally oppose the liberalisation of public services to emphasise this issue, and right-wing parties to de-emphasise it. This reasoning culminates in the first set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a. Left-wing parties will emphasise their position on the issue of liberalising water services.

Hypothesis 1b. Right-wing parties will de-emphasise their position on the issue of liberalising water services.

Concerning issues parties ‘own’, the party can take outlying positions in the sense that they demand a very fundamental policy change or favour policy instruments not supported by the competing parties. Taking an outlying position on issues makes parties distinguishable and helps them to capture (additional) public attention [

44]. In the case of liberalising water services, we assumed left-wing parties ‘owned’ the issue. Therefore, we formulated a hypothesis on the left-wing parties only.

Hypothesis 2. Left-wing parties will take outlying positions on the issue of liberalising water services.

In contrast to salience theory, the ‘riding the wave’ argument posits that a party will refer to issues that feature prominently on the public agenda. In this way, parties can show that they are responsive to public debate [

41,

45]. Public attention for the liberalisation of water services can be regarded as an issue that was high on the public agenda in Germany in 2012 and 2013, and, therefore, was bound to migrate from the public agenda to the political agenda. Which parties are likely to ‘ride the wave’ concerning the liberalisation of water services? Left-wing parties do not need to ‘ride the wave’ since opposing the liberalisation of public services lies at the core of their identity. This kind of strategy is appealing to political parties that hold moderate positions on the issue concerned. If they held extreme positions, changing their position would not be credible to the electorate and, therefore, would not yield the expected results. However, if the party holds a moderate position, it can adopt that of the parties that ‘own’ the issue and potentially gain from this electorally.

Hypothesis 3. Parties with moderate positions on the issue of liberalising water services will change their position and emphasise their new position when the issue’s salience to the public is high.

4. Materials and Methods

Our empirical analysis concentrates on five political parties and how they referred to the liberalisation and privatisation of water services in their election manifestos for eight elections (four at the federal level in Germany and four elections to the European Parliament), in the period 2004–2019. Usually, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU) are treated as one party—or ‘sister’ parties—since they jointly form a parliamentary group and produce shared election manifestos. However, for the European Parliament elections in 2004, 2009, and 2014, the CDU and the CSU produced different election manifestos. We obtained the election manifestos from the parties’ websites; they are publicly accessible.

The observation period selected was long enough to capture different political discussions that took place in Germany, as well as in the EU, concerning the liberalisation and privatisation of water services. In Germany, this issue was on the political agenda in 2000, with a study prepared by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs that recommended the introduction of competition in order to reduce inefficiency in the provision of water services [

46]. At the EU level, in 2003, the Commission announced that it would evaluate the water and sanitation sector in EU member states “with a view to increase competition” [

47]. Most importantly, the period covered several citizens’ initiatives launched in Germany (e.g., in Berlin) and, of course, the ECI Right2Water. To clarify, while our primary research focus was Right2Water and how the German parties reacted to it, by covering a period of 15 years we were also able to assess reactions to other relevant events. In other words, we are aware that this was not a hard experimental setup for testing the isolated effects of Right2Water on the Germany parties’ positions. Rather, we captured additional social and political events and determined how the political parties reacted to these as well. The encompassing database does not threaten the validity of our research design since the hypotheses put forth in the theory section posit general relationships between the variables of interest. Furthermore, as we will demonstrate, the impact of Right2Water was directly observed since some parties explicitly referred to the ECI in their election manifestos.

Election manifestos represent the central documents for testing salience theory. They contain the issues to which parties commit themselves as a collective actor. Of course, individual party members or members of parliament can make statements on certain issues in the media. Yet to capture a party’s position on an issue one has to consult its election manifesto, which represents the outcome of intra-party deliberation and decision-making. The election manifestos are also an important source for news media when they present the parties’ positions on certain issues. The importance of how the media frames parties’ election manifestos can be inferred from the example of the ‘Veggie Day’ proposed by the Greens in their election manifesto for the 2013 federal elections. The daily paper BILD ran an article claiming that the Greens wanted to ban the consumption of meat, which had a negative impact on the votes the party won at the elections [

48]. The basis for this article was the party’s election manifesto and the information provided therein.

Comparative research [

49,

50] as well as empirical studies focusing on Germany [

51] have shown that the policy pledges parties make in their election manifestos are an important determinant of what policies they propose. Parties that do not deliver on their policy pledges have been found to be affected by electoral losses. In the specific case of how policy pledges on water governance materialise in terms of actual public policies, the German city of Stuttgart provides an illustrative example. During the race for mayor of Stuttgart, the candidate of Alliance‘90/Greens, Fritz Kuhn, placed great emphasis on the re-municipalisation of the city’s water services [

52]. When elected into office in 2013, Mayor Kuhn pushed for the re-municipalisation of water services [

53] and filed a lawsuit against the private company EnBW [

54]. While Kuhn’s predecessor, Wolfgang Schuster of the Social Democratic Party, was also in favour of the re-municipalisation, it was Kuhn who acted in a resolute manner to deliver on the policy pledge he made during his electoral campaign. As we will see below, the mayor’s party, Alliance‘90/Greens, is one of the strongest supporters of the re-municipalisation of water services. Another example supporting the close relationship between policy pledges, as expressed in election manifestos, and policy actions, refers to the state of Berlin where, in 2002, the leftist party PDS (now The Left) joined the coalition government and started the process that eventually resulted in the re-municipalisation of water services [

46]. The Left is also one of the parties that are strongly in favour of public water services.

The assumption underlying this analysis is that political parties use specific words in their election manifestos in a purposeful manner in order to participate in party competition by means of offering positions on policy issues, selectively emphasising some policy issues, and engaging in framing policy issues [

55]. Common approaches to generating data from election manifestos include the quantification of texts by enumerating the keywords appearing in them or by measuring the amount of space given to various issues [

39]. For example, the widely used data from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) and its successor, the Manifesto Research on Political Representation (MARPOR), are based on the statements of political parties in their election manifestos, which are coded in a standardised way by means of identifying ‘quasi-sentences’ that are relevant to a given policy domain [

56]. While the CMP/MARPOR dataset is a very useful basis for analysis, the data are assigned to broad categories (e.g., ‘environmental protection’), which do not allow the positions of the individual parties on the liberalisation of water services to be assessed. Consequently, we had to generate our own dataset in order to answer our research questions based on qualitative content analysis [

43,

57,

58].

We relied on the CMP/MARPOR data to operationalise our focal explanatory variable, which is the positioning of the political parties on a left–right scale. There exist different approaches to the measurement of parties’ positions on a left–right scale. A common approach is to place the party on a general left–right scale [

56], taking into account their positions on a wide range of topics. For this analysis, we relied on variable 401 in the CMP/MARPOR dataset, which positions the parties on a continuum regarding their support for a free market economy. It is a more specific as well as more accurate measurement of the dimension of party competition relevant to the present analysis than the general left–right scale.

The greater a party’s score on this dimension, the higher its support for the free market.

Figure 1 visualises the positioning of the parties on the free market by displaying their average score for the years 2005–2017, where 2017 corresponds to the last year for which data were available. We can infer from the figure that the party with the most pro-market position is the FDP, which makes it also the most right-wing party in economic terms, and the party with the least support for the market economy is The Left. However, the positions of the SPD and the Greens are only marginally different from that of The Left. Therefore, we consider this group of three parties—The Left, the Greens, and the SPD—to represent the left-wing parties in the German party system. The CDU/CSU holds a more positive attitude on the free market than the three previous parties, but less so compared to the FDP. Consequently, the CDU/CSU can be considered to have a moderate right-wing position on the free economy.

In a similar manner to the predominant measurement approaches in content analysis, we measured the positions of German parties on the market economy by identifying keywords in their election manifestos [

59]. The keywords of interest for this research were the following:

‘services for the public’ or ‘public services’ (in German: Daseinsvorsorge);

‘public–private partnerships’ (Public–Private-Partnership);

‘liberalisation‘ (Liberalisierung);

‘privatisation‘ (Privatisierung);

‘re-communalisation‘ (Rekommunalisierung).

In a second step, we determined which parties referred to the liberalisation and privatisation of water services in their election manifestos. Based on the extracted statements, we generated a measurement of the salience of the topic to the parties (see

Figure 2) and their positions (see

Figure 3). The data were coded by two researchers who worked independently. The agreement rate between them was 92 percent. The cases where the coding decisions deviated from each other were discussed and solved afterwards.

We operationalised the dependent variables as follows. When parties referred to liberalisation, privatisation or public–private partnerships in either a positive or negative way, we treated the information as an instance of them emphasising their positions (Hypotheses 1a and 1b). We interpreted calls for re-municipalisation of water services as an ‘outlying’ position since it concerns a change in ownership of water utilities and entails the use of taxpayers’ money to buy back water utilities owned by private actors (Hypothesis 2). Changes in positions were measured in what the respective parties demanded in each election manifesto (Hypothesis 3).

In addition, we coded statements that emphasised the cities’ and municipalities’ self-governance rights with regard to water services. We argue that it was necessary to capture these statements since they also represented a strategy for addressing this issue. Indeed, it is an appealing strategy, since the parties can make this statement and not have to elaborate on whether they are in favour or against liberalisation and privation. In theory, this category can comprise any form of public, private or hybrid governance of water services. For example, Schiffler shows that there exist many faces of how water supply and sanitation services can be managed [

12], which also shows that differentiating between public and private arrangement is not always straightforward or meaningful. From the election manifestos, it does not become clear what exactly the parties mean by these statements. Therefore, since we could not discern what exactly the parties’ positions were in terms of governance arrangements, we treated this information as a ‘neutral’ category and, because of that, abstained from formulating a hypothesis on it.

Table 2 summarises the operationalisation of the variables.

We analysed the data in a descriptive manner by means of tables and figures. This approach corresponds to the level of empirical information that our data contained, and was adequate in light of our theoretical argument.

5. Findings

Table 3 below summarises the parties’ positions on the liberalisation and privatisation of water services. The first noteworthy observation was that the FDP only referred to water services and how they should be governed in its election manifestos of 2004 and 2005. After 2005, the party stopped referring to this issue, which resonated with the logic of our first hypothesis: The FDP’s statements in 2004 and 2005 supported the liberalisation of water services.

The CDU’s positioning and emphasising of its respective positions was more dynamic. The party first supported the liberalisation of public services, in the sense that the topic of public–private partnerships could be found in their manifestos for the federal elections in 2005 and 2009. Then, for the 2013 federal elections, the party advocated the self-governing rights of the local level, which corresponds to a neutral position. For the 2014 elections to the European Parliament, however, the party supported the exclusion of water services from the Concessions Directive, which we coded as an anti-liberalisation stance. After that, the CDU stopped positioning itself on this issue.

Even more dynamic was the empirical picture obtained for the CSU. The party was initially against the liberalisation of water services in the electoral campaign for the European Parliament. In the 2005 and 2009 campaigns for the federal elections, it supported public–private partnerships, like its sister party, but in the 2009 elections to the European Parliament, the CSU explained that it opposed liberalisation and privatisation, and again so in 2014. Much like the CDU, the CSU stopped referring to the governance of water services after 2014.

The Left is the party that opposed the liberalisation of water services most consistently over the observation period. It also adopted an outlier position on this issue on many occasions. It was the only party that almost always demanded water services to be re-municipalised. As shown in

Table 3, The Left also explicitly referred to Right2Water in its election manifesto, which underlines the impact of this initiative on the party’s strategic positioning. The same goes for the Greens, who also referred to Right2Water and demanded water services be re-municipalised on two occasions. The Greens consistently opposed the privatisation of water services.

The positioning of the SPD, on the question of how water services should be governed, corresponded to that of the CDU and the CSU in terms of its dynamics, but the changes in positions were more marked than with the previous two parties. As we can infer from the table, the SPD initially supported public–private partnerships in water governance (in 2005). It then adopted an anti-liberalisation stance (in 2009, for the federal elections), and later a neutral stance (in 2009, for the European Parliament elections). In the elections in 2013 and 2014, the party re-adopted an anti-liberalisation stance. The SPD did not refer to water services in its 2017 election manifesto, but in 2019 it demanded that the re-municipalisation of water services be facilitated.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 attempt to visualise the information presented in

Table 2.

Figure 2 shows at what elections the parties made statements on the governance of public services in general or of water services in particular. We can infer from this figure that The Left is the only party to have made statements on water services in all instances. After them come the Greens, who also addressed this issue very frequently. The FDP is the party with the fewest statements on how water services, or public services in general, should be governed.

Figure 3 shows the positions adopted by the individual parties over time. The darker the colour, the more the parties oppose liberalisation and privatisation. The bar graphs range from ‘no position’, to ‘pro-liberalisation’ (which was coded if the parties explicitly mentioned liberalisation and privatisation, though mentions of public–private partnerships were also included), to ‘pro-local’, which only stresses the self-governance rights of the local level. The next two categories concern the parties having an ‘anti-liberalisation’ or ‘pro-re-municipalisation’ position. As with the data presented in

Table 3, we can see that The Left has a very consistent position on this issue, which we can also observe for the Greens. The FDP appears consistent in not referring to this issue in most instances. The parties for which we can observe variation are the SPD (for which we could observe all possible outcomes), followed by the CDU/CSU.

6. Assessment of the Hypotheses

The empirical findings presented in the previous section provided some expected as well as unexpected insights. We begin our discussion with the expected insights and then move on to the unexpected.

Hypothesis 2 postulated that left-wing parties would adopt outlying positions in situations where an issue they ‘owned’ was high on the public agenda. We operationalised an outlying position to correspond to calls for the re-municipalisation of water services. Based on this coding decision, we confirmed Hypothesis 2 for The Left and for the Greens as the two parties that held the most sceptical positions on the free market economy. The SPD also adopted an outlying position, but only for the 2019 elections for the European Parliament. Therefore, the findings for the SPD challenged our theoretical reasoning.

With regard to Hypothesis 3, we did not refer to the parties’ position on a left–right scale but argued that parties with moderate positions on issues may change these in situations where the issues concerned attract public attention and are ‘owned’ by competing parties. Therefore, this hypothesis mostly concerns the CDU, which indeed changed its position subsequent to the ECI and the public debate surrounding it. The party moved from being moderately in favour of liberalisation to being moderately against it. However, this position was only highlighted for a short period of time, which supports the logic underlying the ‘riding-the-wave’ theory. This perspective does not apply to the CSU since that party already held a dismissive stance on liberalisation before it became the subject of public controversy in 2012 and 2013. Neither does the argument apply to the SPD since the party is affiliated with trade unions and should be one of the parties that ‘own’ the issue. Therefore, we can state that the CDU indeed rode the wave and made an attempt to position itself strategically on the issue of how water services should be governed.

Turning to the first set of hypotheses, we can confirm Hypothesis 1b for the FDP, but we cannot confirm it for the CDU/CSU. The latter changed positions and emphasised the new ones. To be more precise, in the case of the CSU we observed that the party issued different positions depending on whether it was an election to the Federal Parliament (in that case, it accepted the position of the CDU) or an election to the European Parliament (in that case, it formulated separate strategic documents). The CSU’s volatility in how it positioned itself on this issue is one of the most striking findings of this analysis, as were the findings for the SPD. Despite being a left-wing party, the SPD at one point supported public–private partnerships and in other instances de-emphasised its position on this issue, despite the issue ‘ownership’. Therefore, with regard to Hypothesis 1a, we must reject it for the SPD, but can confirm it for The Left and the Greens.

Overall, our theoretical reasoning proved more accurate when applied to smaller parties (FDP, the Greens, and The Left). The bigger parties, of which at least one has always participated in coalition governments, turned out to be less consistent in their strategic behaviour over time. This finding does not challenge the theoretical perspective applied here, but it suggests that it is worth considering additional factors for explaining the behaviour of the major parties.

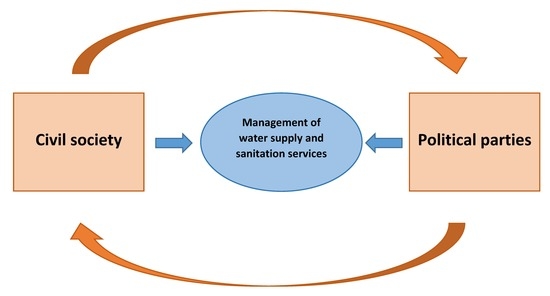

7. Conclusions

In this study, we examined how political parties in Germany reacted to enhanced public attention on the issue of liberalising and privatising water services. We adopted this particular research perspective in order to complement research investigating the role of social movements on the management of water supply and sanitation services. While civil society has become heavily involved in this issue, we must not neglect how conventional political actors have reacted to the societal demands. In this regard, political parties are worth investigating since their main function is to aggregate and articulate policy demands and, when elected into office, deliver on the respective policy pledges made.

Our analysis revealed a left–right division in terms of both the parties’ referral to how water services should be governed and their positioning. The FDP, as the most pro-market-oriented party, did not refer at all to the liberalisation of water services in 2009–2019. In 2004 and 2005 it supported liberalisation. The CDU/CSU referred to water liberalisation in more instances than the FDP, but with changing positions. The overall position of the SPD was one sceptical of liberalisation, but at times this party also supported the involvement of private actors. Only the Left and the Greens held dismissive and outlying stances on this issue for the entire observation period. We could also show that the CDU rode the wave of opportunity in 2014 as it tried to capitalise on its support for water services being removed from the Concessions Directive.

What do these findings contribute to the literature? First, we showed that parties do respond to civil society initiatives such as Right2Water. Second, our findings revealed that their responses depended on whether they ‘owned’ the issue concerned or not. Third, we uncovered that riding the wave was used as a strategy in this particular case.

We are confident that this analysis provides novel insights into how ECIs affect party politics in the EU member states. Nonetheless, the analysis is limited in its theoretical perspective as well as in its empirical approach. From a theoretical perspective, it would have been desirable to model the relationship between political parties and social movements. Concerning the empirical approach, we adopted a rather simple measurement of the dependent variable, which did not capture all forms of how water supply and sanitation services can be managed. In this context, it would also have been interesting to assess more precisely the scope of liberalisation and privatisation as supported by some parties, especially concerning sanitation services. However, these limitations of the current study provide avenues for future research.