Virtual Teaching in the Time of COVID-19: Rethinking Our WEIRD Pedagogical Commitments to Teacher Education

- Department of Curriculum and Teaching, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

Teacher Educators confront a professional future in which online instruction will play an increased role in student learning. As instructional activities are delivered online, a critical challenge for teacher educators will be to continue supporting those ideals key to the missions of many Schools and Colleges of Education—the creation of an instructional environment that is culturally responsive, committed to equity and inclusion, and able to support a diverse and “well” student body.

Introduction

Shifting to virtual instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic has forced a rethink by teacher educators who do not normally teach or design online course content. As educators in professional schools, we teach in settings where learning is not an abstract art. It is a professional endeavor marked by State and National standards, field experiences, and standardized professional exams, and our students enter our courses with scripts, schemas, and imagined notions of what it means to teach and foster learning. Thus, as the global pandemic accelerates a continued rise in virtual learning, teacher educators must re-examine what it means to (1) be responsive, equitable, and inclusive to the individual needs of a diverse pre-service (undergraduate) teacher population and (2) attend to the collective professional needs and imagined identities of these students as these pursue their initial degrees online.

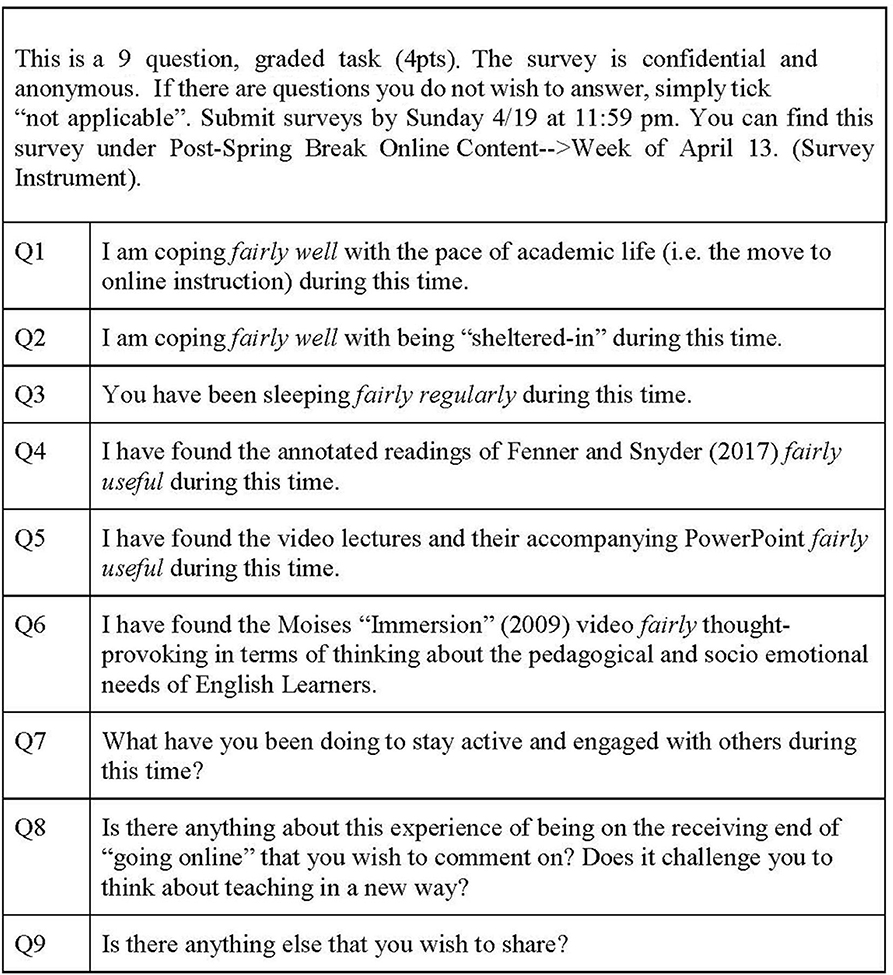

To this end, the following manuscript details my personal reexamination and process of coming to know the personal, practical, and pedagogical needs of my pre-service students as learners—and in particular as virtual learners—during the Coronavirus pandemic. I present the results of a “Wellness Check and Online Feedback Survey” (Figure 1). I created and administered this survey to two sections of my undergraduate TESOL methods course 4 weeks into our shift to virtual learning. The survey encompasses several pedagogical commitments important to the mission of my School and to my work with students—a commitment to “wellness,” “equity, inclusion, and diversity,” with a healthy dose of “culturally responsive pedagogy” added to the mix. I refer to these practices by the memorable, even if a bit pejorative, acronym—WEIRD. Through the survey, I inquire into my students' experiences of being sheltered in and completing my course online. Adopting a thematic analysis of the data, I present the results of the survey along with their implications for virtual pre-service teacher education.

To contextualize this work and its findings, I begin with background literature on the three conceptual frameworks that undergird my WEIRD pedagogical practice. This literature draws primarily from the field of Self-Study with its emphasis on the personal, practical, and relational nature of professional practice (Hamilton and Pinnegar, 1998; Pinnegar and Hamilton, 2009). Next, I introduce three frameworks from the field of virtual education: Principles of Instructional Design, Community of Inquiry, and Role Theory. I present literature on these frameworks, incorporating scholarship that similarly adopts WEIRD pedagogical practices. I then discuss the professional tensions that drove my online course design and instructional approach during that pandemic semester. Finally, in the spirit of reflective scholarship, I present this research from the first-person (“I”) perspective. In doing so, I emphasize the situatedness of these findings to my work as a teacher educator and my attempt to “respond to the current and emergent needs of [my] constituencies” (Hamilton and Pinnegar, 2000: 234) during this specific moment in history.

Background

The following section “introduces, clarifies, organizes, and establishes the purpose and focus of” (Hamilton et al., 2020: 319) the survey I administered to my pre-service teachers in April 2020. The purpose and focus, as well as the interpretation of the survey results, are in dialogue with (1) my WEIRD pedagogical frameworks, (2) instructional theories drawn from the field of virtual education, and (3) professional tensions that shaped my move to virtual teaching.

WEIRD Pedagogical Frameworks

My WEIRD pedagogical frameworks consist of instructional and curricular commitments to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Culturally Responsive Pedagogy, and “Being “Lazy” and Slowing Down” (Shahjahan, 2015). A brief overview of each framework follows.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

Through commitments to DEI, teacher educators seeks to address barriers to access and achievement in institutional spaces. Traditionally, these commitments have focused on historically marginalized groups—students of color, first-generation students, low-income students, and differently abled students. Increasingly, commitments to DEI have included addressing education's “moral and legal obligations” to LGBTQ (Kitchen and Bellini, 2012: 209) and visible religious minority students (Lumb, 2016). These commitments have encompassed also the work to internationalize educational institutions in ways that honor and support the linguistic diversity on campus and within classroom spaces for learners who are speakers of additional languages, as well as dialect and vernacular speakers (Cruickshank, 2004; Barton et al., 2015; Dunstan and Jaeger, 2015).

Teacher educators signal their commitment to DEI in a number of ways. They adopt a Universal Design of Learning (Evmenova, 2018) and enact pedagogical practices that connect with students on the level of identity and well-being. They take up instructional activities that engage students in critical discussions of “authentic” and “brave” texts that connect to the lives and foster “higher-level thinking” (Ballentine and Hill, 2000: 11). They even bring into their course curricula material that “challenges, confronts, and disrupts misconceptions, untruths, and stereotypes that lead to structural inequality and discrimination based on race, social class, gender, and other social and human differences” (Nieto, 2006: 2).

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP)

Through commitments to CRP, teacher educators work to improve the learning outcomes of students historically marginalized within the U.S. (Ladson-Billings, 2009; Gay, 2018), as well as manifestations of this marginalization experienced by multilingual, multiliterate, and transnational learners within the U.S. and around the globe (Thomas and Carvajal-Regidor, 2020).

Additionally, CRP advocates for teaching that is supportive of students' linguistic heritage. Such advocacy may include adopting a participatory approach to student learning, one that draws upon students' cultural and linguistic resources as a point of reference for instruction. Moreover, it is an approach that works to raise the critical consciousness of students, to empower them to engage with and push against the dominate ideologies that erase, exclude, or negate their lived experiences and personal knowledges. In adopting a culturally responsive approach to pedagogy, teachers authorize and legitimize these resources in ways that are linguistically and culturally sustaining (Paris, 2012) and revitalizing (McCarty and Lee, 2014).

Finally, CRP encourages a relational approach to pedagogy that, for some educators, embraces emotional vulnerability (Coia, 2016). Acts of self-disclosure may entail, for example, delving bravely into the pedagogical tensions that surface in one's own practice. Through these acts, educators model an “ethos of care” that works to create an instructional space capable of “establishing flexible and supportive relationships with students” (Han et al., 2014: 299).

Being “Lazy” and Slowing Down (BLSD)

While concepts of wellness vary in higher education, Shahjahan's call to “be lazy” and “slow down” (2015: 488) offers a different notion of wellness. BLSD attempts to address the impact of “neoliberal values of competition, privatization, efficiency, and self-reliance” (Hartman and Darab, 2012: 52) on the mind, body, and spirit of those within Higher Education. These neoliberal values privilege the embodiment of knowledge in the mind and at the exclusion of the body and spirit (Shahjahan, 2015). In contradistinction, BLSD advocates for pedagogy that engages learners in knowledge production through “deliberate and meaningful” bodily rituals (Mayuzumi, 2006: 9), “deep reflection, experiential learning and reflexivity” (Hartman and Darab, 2012: 58), and building relationships and nurturing creativity (Shahjahan, 2015).

Together, these WEIRD pedagogical frameworks anchor my curriculum-making and instructional practice. Similar frameworks have been adopted by scholars in the field of distance and virtual education. In the next section, I introduce three theories that play important roles in virtual education scholarship, and I provide example of how these concepts have been WEIRDly adapted for the virtual learning environment.

Virtual Education Instructional Theories

In this section I discuss three theories drawn from virtual education instructional literature: Gagné's Principles of Instructional Design, Community of Inquiry, and Role Theory.

Principles of Instructional Design

Richey (2000) categorizes principles of instructional design as consisting of both macro- (site design) and micro- (instructional design) elements. The latter, the micro-design elements, hold pedagogical import for educators. Moreover, these micro-design elements traditionally have been grounded in the instructional design theories of psychologist Gagné (2000).

For Gagné, “learning is fundamentally viewed as an internal process,” one that is facilitated by attention to learning hierarchies, design and sequence, as well as learners' background knowledge and the input given to them during instruction (Richey, 2000: 255, 256). Fundamental to Gagné's work are nine external instructional actions that must occur in order to activate the internal processes that will foster student learning. These actions or “events…serve as a conceptual model for the design of lessons, the selection of instructional strategies, and the sequencing of instruction” (Richey, 2000: 269). The nine events include stimulating or gaining attention, informing, recalling, presenting, guiding, eliciting, providing feedback, assessing, and arranging (Gagné et al., 2005: 192).

The confluence of Gagné's principles of instructional design with WEIRD pedagogy is reflected in Compson (2017). Through instruction designed to promote “significant” and “deep” learning experiences through contemplative practices, her course “Philosophy, Religion and the Environment” critiqued the role of technology in human lives (2017: 108, 107). The course alternatively created opportunities for students to disengage from their computers, engage with the natural world, and partake in practices of deep reflection through artwork, photos, poetry, and/or video (Compson, 2017: 107). As students moved through the semester, they would recall and recycle the contemplative skills learned earlier in the course (prior knowledge), increasing their proficiency in these practices “through the processes of differentiation, recall and transfer of learning” (Gagné, 2000: 44). Instructional practices adopted in the course mirrored the kinds of external instructional events that Gagné posits spark internal learner motivation.

Community of Inquiry (CoI)

Fostering a sense of community is important to learning; it can generate an emotional connection or sense of belonging with fellow learners that “increase[s] the flow of information, the availability of support, commitment to group goals, cooperation among members, and satisfaction with group efforts” (Rovai, 2000: 286). In virtual spaces, where learners are not co-present, scholars promote a “Community of Inquiry” (Garrison et al., 2000). This inquiry-based approach to online pedagogy provides students with the cognitive and social opportunities that foster critical thinking, deep and meaningful learning, and internal motivation in text-driven and asynchronous spaces (Fiock, 2020).

CoI promotes three types of online interactions or presences—cognitive, social, and teaching. Cognitive presence is fostered through pedagogical activities that create cognitive dissonance for learners around a problem or topic of inquiry, a “triggering event” (Garrison, 2007: 65). The triggering event is used to guide students to explore, integrate, reflect on, and reconstruct “new meaning around that topic through sustained communication” (Garrison et al., 2000: 89). Social presence is afforded when instructional activities allow learners to establish a personal, expressive, and cohesive group self online. These activities draw students into a “shared experience for the purposes of constructing and confirming meaning” (Garrison et al., 2000: 95). Finally, teaching presence encourages both cognitive and social presence through the design and facilitation of online teaching. Facilitation incorporates such activities as modeling discourse and providing feedback through “short messages acknowledging a student's contribution” (Garrison et al., 2000: 96).

The importance of cognitive, social, and teaching presence on learning and community, and the challenge for virtual learning when these presences are not cultivated, can be seen in Tan et al. (2010). While Tan and her colleagues do not use a CoI framework or make reference to these three presences, their work nonetheless demonstrates the impact on learning and community when these presences are absent. Through interviews with international graduate students for whom English is a Foreign Language (International EFLs), the scholars found that the online classes taken by these students were embedded with technical, linguistic, and cultural practices that assumed universal knowledge and practices. These include use and familiarity with course management systems, acronyms and vernacular phrases, and comfort levels with self-disclosure of “personal experiences, feelings and opinions” (Tan et al., 2010: 12). Without appropriate instructional intervention, the virtual environments failed to provide these International EFLs an inclusive, equitable and culturally responsive online space. As a result, these students were unable to negotiate the cultural, linguistic, and technological skills needed to learn and cultivate community with their peers.

Role Theory

Role Theory highlights the varied and shifting roles individuals can assume in an interaction or task. The roles reflect the “social positions” and the accompanying “scripts or expectations for behavior” (Biddle, 1986: 67, 68) required of the role bearer. While roles are not fixed, established roles may diversify or shift as the context of instruction necessitates over the course of a semester, unit, or even a class.

Several role shifts for teachers have been documented in their move to virtual instruction (Coppola et al., 2002; Walker and Shore, 2015). One such shift occurs in the diversified pedagogical (cognitive) role assumed by instructors. This shift includes facilitating teacher-to-student and peer-to-peer dialogue, responding to questions, and providing feedback (Dunn and Rice, 2019). These roles are present in face-to-face teaching, but must be carried out differently in the virtual space. Social roles may shift as teachers and students work to negotiate interactions virtually and asynchronously. Further, instructors may encounter significant shifts in their managerial role as they attempt to structure online pacing for student progress and success. This managerial role may even overlap with a diversified technical role and need to facilitate new uses of technology, first by the instructor and then by the student (Keengwe and Kidd, 2010). Finally, an expanded affective role (Coppola et al., 2002) requires of teachers new ways to manage, transpose, and use oral, non-verbal, and paralinguistic cues to negotiate meaning-making, the up-take of knowledge, and provided supportive and effective feedback.

Positing the need for an intentional shift in pedagogical and social roles in virtual learning environments, Knowlton (2000) advocates for an instructional shift from teacher-centered to student-centered pedagogy. Such a shift requires a diversification in both the teacher and student roles (Walker and Shore, 2015). Knowlton explores this diversification of roles through Connelly and Clandinin (1988) categorization of classrooms into things, peoples, and processes. He contrasts the roles and behaviors enacted in a student-centered vs. teacher-centered engagement with classroom things, peoples, and processes. In doing so, Knowlton foregrounds the agentive part students can play in incorporating knowledge and developing ways of knowing that are meaningful to them and reflective of their interests.

In introducing the frameworks that undergird my WEIRD pedagogy, and by foregrounding the aforementioned theories grounded in virtual education, I have established the scholarly foundation on which the survey and results are to be understood. I next introduce the context that gave rise to the survey.

The Shift to Virtual Learning During COVID

In March 2020, my University shifted to 100% virtual instruction. At the time, I was teaching two sections of a required TESOL methods course to Middle/Secondary Pre-service Teachers. Course instructors were given a week to prepare for the shift online. While the limited turn-around time given to adapt our classes for virtual instruction was stressful, I felt particular tension about my ability to attend to the WEIRD needs of my diverse student population. Tensions, according to Berry, are “feelings of internal turmoil experienced by teacher educators as they [find] themselves pulled in different directions by competing pedagogical demands in their work and the difficulties they experience[] as they lear[n] to recognize and manage these demands” (2007: 119). Berry takes up the notion of tensions as “a conceptual frame and analytic tool,” presenting tensions “in terms of binaries in order to capture the sense of conflicting purpose and ambiguity held within each” (2007: 119, 120).

In a similar fashion, I present the tensions that accompanied my shift to virtual teaching. For example, as colleagues were planning to hold synchronous meetings with their students, I experienced tensions related to “space” and “place.” Although some of my students were headed home to places as close as the neighboring county, others were returning to spaces located in different time zones and on different continents. In addition, I experienced tensions concerning “the written” and “the read” word. Folk perceptions of online learning call up images of students spending significant time in front of a screen as they attempt to negotiate and communicate meaning through reading and writing. I feared the overreliance on these two modalities would create an unequal cognitive load for my international EFLs and contribute to screen exhaustion and eye fatigue. Moreover, I experienced tensions around “access” and “engagement”; not all University students have access to personal laptops and computers. Some students rely on computer rentals from the University Libraries and use campus computing stations to access specific software programs (like SPSS). Finally, while WIFI is available readily on campus, students living off campus may have limited or no internet access beyond their mobile phones.

To accommodate these tensions, I designed my virtual course as a self-paced learning module designed around a triggering event (Garrison, 2007), a short fiction film titled, “Immersion” (Levien, 2009). This 12-min video follows several days in the school life of an immigrant child. The student, Moises, excels at Math. Yet, due to his novice-level proficiency in speaking and reading English, he struggles academically and socio-emotionally in class. The specific triggering event for this film centers on an upcoming standardized test and the frustration experienced by Moises's teacher to provide him with the pedagogical supports he needs to demonstrate his content knowledge rather than his English language proficiency.

The self-paced module provided students with a clear pedagogical challenge. Moreover, this was a challenge in which negotiation of meaning was not based on reading proficiency or comprehension, but on the ability to critically look, observe, and listen to the video. In addition, the module included annotated weekly readings. I highlighted key sections of the texts and I provided hand-written comments in the margins to facilitate meaning-making. I created audio-recorded PowerPoint lectures that accompanied each week's activities. The aim was to provide students with a respite from reading, while also supporting development of English listening skills for my international students. Finally, I designed our virtual classroom space with the most basic computing and internet access in mind—the cellphone. Tasks were designed to be downloaded and accessed offline, video streaming was limited, online quizzes were designed with clickable true or false responses, and students were given the opportunity to audio/video record (rather than write) their assignments.

Four weeks into our new virtual and sheltered-in reality, I decided to check on students' well-being and gauge their perceptions of aspects of the self-paced learning module. Guided by my WEIRD commitments to pedagogy, a rudimentary knowledge of virtual instructional theories, and several tensions related to curriculum-making, I created and administered an online survey. The survey was designed to assess student (1) well-being under the pandemic and (2) perceptions of the pedagogical supports implemented to foster learning in this new virtual setting—the text annotations, a central text based on a triggering event, and audio-recorded video lectures.

Materials and Methods

Wellness Check and Online Feedback Survey

The survey consisted of six closed-ended (5-point Likert scale) and three open-ended questions (Figure 1). Using my University's course management system (CMS), the survey was distributed to two sections of my undergraduate middle/secondary TESOL methods course. The CMS survey design grants a relative degree of anonymity. Although the system identifies which students have not responded to the survey, it does not provide information on individual survey responses. Instead, the system generates raw and percentage aggregates of the results. To encourage student submission of the survey, course activities were suspended for the week during which the survey was open. In addition, students received a completion grade for submitting the survey, resulting in a response rate of 92% for the morning section (N = 22/24) and 89% for the afternoon section (N = 16/18).

As the survey was not originally designed for research purposes, the instrument was not pre-tested or validated beforehand. Following data collection, IRB approval was acquired to use the previously collected and de-identified survey data, and the survey was forwarded to colleagues for validation. In particular, construct validation was sought to determine the survey's ability to assess student cognitive, socio emotional, and physical well-being (pace, emotional stability, and sleep), as well as elicit student perceptions about the pedagogical adaptations made to the course. Positive feedback was provided on the question (item) design, clarity, and construct validity; while caution was noted toward the use of a fifth and neutral category (“neither agree nor disagree”), as such responses are “more difficult to endorse” (Nemoto and Beglar, 2014: 5) and can present challenges to data analysis.

The Analyses

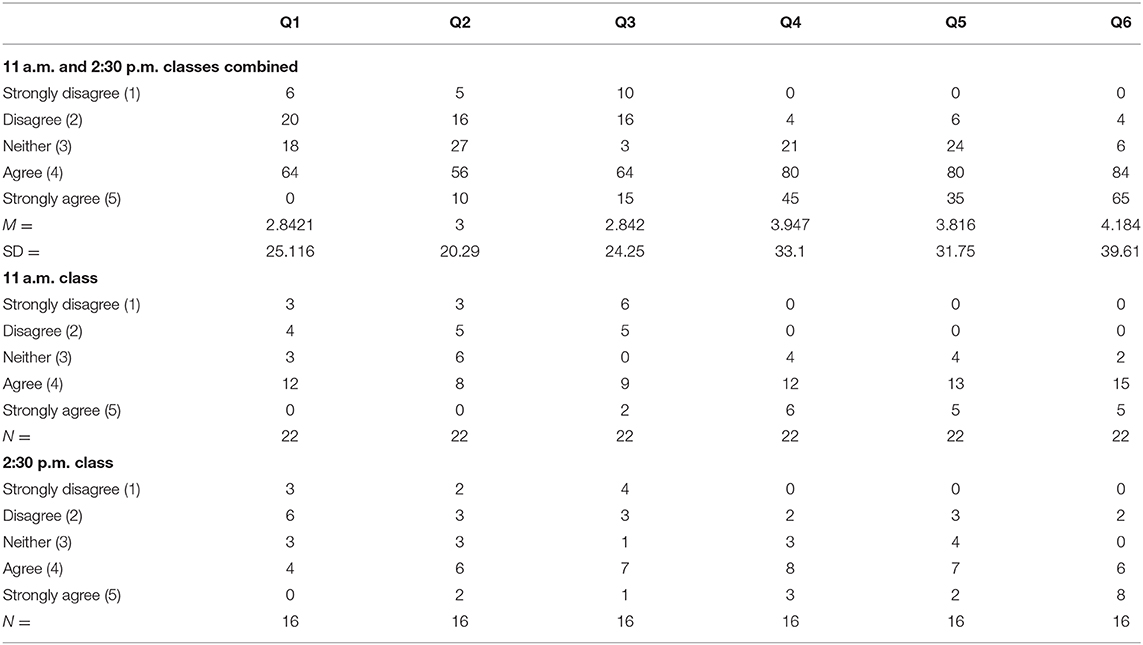

Table 1 presents the raw data from the closed-ended questions (Q1–Q6). The raw data for both classes was combined and the Mean (M) and Standard Deviation (SD) were calculated (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree) (see Table 1).

Responses to the open-ended questions (Q7–Q9) for the two classes were combined and then analyzed using a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Clarke and Braun, 2017). Adopting a semantic approach to coding (Braun and Clarke, 2006), each data set was examined for repeating patterns of words, phrases, and even metaphors. The data was reviewed multiple times, initial codes and coding categories were identified from these word patterns, and overarching themes drawn. The data then was reanalyzed across all data sets (Q1–Q9) to determine if any differences in core themes surfaced across the combined data sets.

The analyses were conducted in conjunction with a graduate student who completed his college teaching experience under my supervision in both sections of the course. Individually we coded, shared, and discussed the data and analyses, while together we discussed and refined our respective analyses to add trustworthiness to the results. The final results were triangulated with my end-of-course evaluations and with current scholarship from the field.

Results

Within the Data Sets

Closed-Ended Questions (Q1–Q6)

In terms of how well students were faring under COVID (Q1–Q3), less than half, 42%, agreed (n = 16) they were coping “fairly well” with academic life (Q1: M = 2.84, SD = 25.12); while 26% disagreed (n = 10) and 16% strongly disagreed (n = 6) with this statement. In addition, less than half of students, 42%, agreed (n = 14) or strongly agreed (n = 2) that they were coping “fairly well” with being sheltered in, while 34% disagreed (n = 8) or strongly disagreed (n = 5) with this statement (Q2: M = 3.00, SD = 20.29). While 50% agreed (n = 16) or strongly agreed (n = 3) that they were sleeping “fairly regularly,” 47% disagreed (n = 8) or strongly disagreed (n = 10) with the statement (Q3: M = 2.84, SD = 24.25). The results of these three questions suggest less consensus amongst students in their responses to living and studying under COVID—while some students were coping, others were coping less well.

In terms of the instructional adaptations for the class, 76% agreed (n = 20) or strongly agreed (n = 9) the annotations were “fairly useful” (Q4: M = 3.95, SD = 33.10), while 71% agreed (n = 20) or strongly agreed (n = 7) the video lectures were “fairly useful” (Q5: M = 3.82, SD = 31.75). Finally, 89% agreed (n = 21) or strongly agreed (n = 13) that the triggering event, “Immersion,” was “fairly thought-provoking” in terms of considering the pedagogical and socio emotional needs of English Learners” (Q6: M = 4.18, SD = 39.61). The results of Q4–Q6 suggest there is more consensus amongst students in their responses to my pedagogical adaptations, than to their responses about how they were faring (Q1–Q3) under COVID.

Open-Ended Questions (Q7–Q9)

In response to Q7, “What have you been doing to stay active and engaged with others during this time?” (n = 37/38; 1,524 words), three themes were drawn—working, recreating, and reconnecting. Working includes schoolwork (“building my teaching portfolio”), but also employed work where students acquired new jobs, picked up extra hours (afforded by asynchronous course structures), or worked jobs where they were deemed “essential workers.” Recreating—as in participating in recreational activities—encompasses technology mediated activities (“watching movies”, “video chatting,” “playing video games,” “making TikToks,” “reading,” and recreational “cooking”), indoor (“working out in my basement,” “playing board games,” “clean[ing] house,” doing “relaxing yoga videos online”) and outdoor activities (“skateboarding,” “running,” “hiking,” and “going on walks,” either alone, with dogs, with family, friends, and/or significant others), and creative pursuits (“painting,” “singing,” “playing guitar,” “embroider[ing],” and “doing house projects”). Reconnecting highlights themes of engaging with and returning to people (family, friends, and significant others) and activities (“running outside”).

In response to Q8, “Is there anything about this experience of being on the receiving end of “going online” that you wish to comment on? Does it challenge you to think about teaching in a new way?” (n = 35/38, 2,354 words), three themes were drawn—pace, space, and face-to-face. Pace refers to the perceived load of working online. For some, this pace of online work was increased intentionally by instructors (“as an excuse to assign more work”) or as a by-product of simply working online (“extra time needed to do my work,” “takes me much longer,” “easy to get behind”). For others, a positive awareness of the impact of the change in academic pace was noted (“a lot can be done on your own,” “I can work at my own pace”). Space references concerns about “lost access” to University spaces, such as “a study space” (like those provided by the “libraries” and “dorms”); as well as “campus resources” (such as technology “capable of handling [one's] workload”), engagement with peers, and loss of what one student called, a “productive environment.”

The theme of face-to-face is associated with a variety of student phrases— “normal direct-teaching,” “human connection,” “in the classroom with hands-on learning,” “lessons in real time,” assignments that “seem[ed] more real” and were viewed as “more effective,” and that “provided deeper” and more “meaningful” learning. Several students commented on a class that used “weekly Zoom meetings to carry out discussions,” with one comment stating that the Zoom course was “more productive than a video recording” as it allowed students to receive “instant feedback” and “more deeply analyze the content with…peers.”

Finally, these three themes of pace, space, and face-to-face were frequently accompanied by boulomaic modals (“I hate,” “I hope,” “I miss,” “tripled in ferocity,” “thrown in the garbage,” “don't like,” “and quite negative”) and adjectival (“harder to learn,” “hard to stay focused,” “hard for the learner,” “hard for the teacher,” “normal…teaching,” “lost out”) expressions.

In response to Q9, “Is there anything else that you wish to share?” (n = 24/38, 1,535 words), three themes were drawn: thinking, thanking, and struggling. Thinking is associated with a variety of modal expressions to describe the emotional (boulomaic modality) and knowledge stances (epistemic modality) of self or others. Through statements such as “I fear,” “I feel,” “it just is sad,” “I miss,” “I hope” and “I do not think” or “I should,” students demonstrate their reflection on, rather than anxiety about, their lives under COVID. Thanking—expressed by both the verbs “thank” and “appreciate” —represents expressions of gratitude for the flexibility of my course as it moved online, for the time I took to check on their well-being, and “for being so understanding during these times.” Thanking further includes expressed appreciation (“thankful”) for their life and health (and that of their family) and for marginalized students “who struggle to find resources” to pursue their educations. Finally, struggling reflects students' attempts to keep up with course work and/or to manage their mental health, anxiety, and depression during this time.

Across the Data Sets

Below, I highlight themes shared across Q1–Q9, drawing out commonalities that surface as salient when compared across the data sets. Three overarching themes were identified: (1) coping with the shift to online learning and the disruption caused by the pandemic, (2) missing and mourning the loss of structure and support the University provides, and (3) lamenting lost connections to people, resources, ideas, and educational content that in-person teaching affords.

Coping

Across the data sets, the concept of coping surfaced, but in different ways. For some students, the pandemic and shift to fully online classes provided opportunities to reconnect with family and friends and/or work increased hours due to the cancellation of in-person classes. This positive sense of coping is reflected across the open-ended responses, as well as the closed ended-responses through agreement or strong agreement for the questions posed. For others, “struggle” marked the early days of sheltering in and studying online. Struggle was a result of increased workloads, financial insecurity, and contact with the public as an “essential worker.” Struggle was a consequence of the stress of managing pre-existing and chronic conditions, such as “anxiety,” “depression,” “ADD” and “asthma.” Struggle was a reflection of the socio emotional challenges of adapting to new ways of engaging with course material, taking up knowledge, and living through the new reality of their college experience. This negative sense of coping— “trying to make it, day-by-day” —is reflected across the open-ended responses, as well as the closed-ended responses where disagreement or strong disagreement for Q1–Q3 were expressed.

Structure and Support

Across the data sets, students referenced and mourned the disruption to their accustomed academic support structures due to the shift to virtual instruction and subsequent campus closure. Their responses highlighted the routine (the regularity of “going to class”), support and motivation (through “in-class reminders”), and access (to a “distraction free and academically oriented environment”) campus life provides. They further commented on the loss of support and access to mental health the University provides, both in terms of campus services and the regular social connections and interaction campus life provides. These two factors, access and interactions, were cited by students as increasing motivation and fostering “self-responsible” and “accountable” behaviors. Finally, while the self-paced class allowed needed flexibility for some students, for others the absence of interaction in the self-paced environment felt like “a lack of support.”

Connection

Across the data sets, students lamented the loss of several connections due to the shift online. This loss included connections to people, expressed through such phrases as “human connection,” “in person interaction,” “in person lectures,” and “hands-on learning.” Loss also included a deeper connection with course material through instructional activities. This latter sentiment was echoed in my course evaluations, with one student calling for “fun activities, authentic videos, and virtual supplementary resources that help with instruction.” Loss also included connection to campus resources, such as access to computers, the internet, and spaces to study. Yet, while most references to connection were associated with loss, some were associated with gains. A number of students expressed a deeper appreciation for the ways one's “socioeconomic” and “socioemotional” environment can negatively affect student learning and academic success. They also expressed appreciation for teaching that is student-centered instruction, interactional, and engaging.

Discussion

The “Wellness Check and Online Feedback Survey” provides important insights into the cognitive, socioemotional, and physical well-being of my students during the first wave of the Coronavirus pandemic. In the section that follows, I explore three implications that findings from the survey have for my professional practice and for teacher education. I discuss these implications in relation to the WEIRD pedagogical practices and virtual education theories introduced previously and to the pedagogical activities I carried out that spring.

Mastery

The first implication of the survey findings is that virtual pre-service teacher instruction ought to attend to student fears about losing out on experiences associated with attaining professional mastery— “student teaching,” “hands-on learning,” and “creative…instruction.”. While the aforementioned experiences imply an active student presence, they also imply an active teaching presence, one that requires a shift and diversification in the enactment of the teaching roles traditionally taken up in support of student professional mastery.

In my traditional face-to-face role as more knowledgeable other (Vygotsky, 1978), I attempt to foster student mastery in working with English Learners by modeling the “competencies and technical skills associated with performing specific tasks required by the discipline or profession” (Anderson, 2001: 31). This modeling includes presenting methods of planning, adapting, and using language in instruction and asking questions in order to probe student thinking about the appropriateness of different pedagogical actions. In virtual education, however, this teaching role is diversified to include pedagogical actions such as pointing out, highlighting, and hyperlinking to the things, peoples, and processes in the virtual space that can assist students in accomplishing these same goals. Moreover, this pedagogical role overlaps with a new “technical role” where I am responsible for designing a virtual learning environment that “make[s] explicit and visible what was formally invisible” (Anderson, 2001: 30).

Stepping into these diversified and new pedagogical roles means that the self-paced module I designed around the fictionalized film, “Immersion,” required clear instructional and technical interventions to be built into the design and implementation of the course. For example, I needed to clearly and systematically guide students' attention to the “things” (bilingual dictionary, instructional materials hanging on the classroom walls), “people” (bilingual peers; a willing, albeit questionably capable, teacher), and “processes” (paired classroom seating that could have turned into a think-pair-share activity) that appeared in the film and that could inform pedagogical action in that learning context. This is a technical role I would have taken up in an impromptu fashion in a face-to-face classroom, but I would need to plan in advance in the online setting. Such online guidance could have been facilitated by the use of video annotating software like VoiceThread. With this software I could provide voice-over annotations to accompany specific scenes in “Immersion” that guide, point out, and make pedagogically relevant connections between teaching and the ecological context of learning. This act of increasing my teaching presence by modeling the “artistry” of my practice (Schön, 1987: 13) encourages an active role for students in their knowledge-construction process and in the development of their teaching mastery.

Motivation

The second implication of the survey findings is that virtual pre-service teacher instruction needs to address student motivation. For my students, lowered motivation that spring was a result of a number of factors—stress, anxiety, and uncertainty. However, it was also due to a lack of intellectual and interactional engagement with the asynchronous classroom space I had designed. As Gagné et al. (2005) point out, deep learning is tied to student engagement with meaningful activity, and both learning and engagement play a significant role in sustaining internal motivation for learners. Design of virtual spaces must take these factors into account. In particular, instructional design of virtual instructional activities must draw upon cognitive and teaching presences to activate the external actions that could lead to internal motivation. These activities must also reflect that peer-to-peer interactions, supported by instruction that allows for social presence, positively influence student motivation in online learning.

Thus, to activate internal motivation across an inclusive range of students, I needed to create my self-paced course as a Community of Inquiry (CoI). This CoI would be designed around student-centered activities that afforded an interplay of engagement between cognitive, social, and teaching presences. Activities in this CoI would engage student cognitive presence through activities that draw out student background knowledge and interests. Such activities include instructional practices that foreground the learning objectives for each activity, make explicit connections between new and previously learned topics, provide explicit guidance, and enhance knowledge retention and transfer (Gagné et al., 2005). Rather than relying on self-grading reading quizzes to support this last goal of knowledge retention and transfer, I could have followed up the annotated reading assignments by having students discuss the readings in small groups—either synchronously in Zoom breakout rooms or asynchronously via discussion boards on our course management system. Both spaces provide opportunities for dialogue, interaction, and social presence. These opportunities not only foster internal motivation but also support my international EFLs' opportunities to engage virtually with their U.S.-based peers.

Additionally, I needed to address the heightened anxiety experienced by some students concerning the feared impact the virtual experience would have on learning, course grades, and upcoming field experiences. To address this anxiety, I could have extended the notion of peer-to-peer interactions to include contact with an imagined community (Anderson, 1983) of professional teachers and through extension, their students. For example, I could have recorded informal interviews with in-service teacher I knew who were working with English Learners and shared their on-the-ground challenges with my students. The recorded interviews could have been followed up by student searches on the internet to find and share new stories and video clips of K-12 teachers and English Learners across the globe—English as an Additional Language and English as a Foreign Language—facing similar challenges. Such instructional engagement would afford students the opportunity to discuss as a community the experiences their imagined community of fellow teachers and their students were encountering in virtual learning and perhaps even relate these experiences to their own. In this way, students would be engaged in meaningful actions that could potentially stimulate and support their internal motivation.

Mythology

The third implication of the survey findings is that virtual pre-service teacher instruction should support student mythology surrounding the collegiate experience. By mythology, I refer to the imagined and anticipated expectations of what undergraduate life should entail. The existence of this mythology is reflected in respondents' expressions of longing and angst about loss in the shift to online learning—the lost semester, lost interactions, lost experience. It is also reflected in expressions about feeling cheated of the college experience. To support the esprit de corps that fosters the mythology of undergraduate life, virtual instruction must attend to the individual and collective student mind, body, and spirit through support of both student and teaching online presences.

My self-paced module failed to account for this loss or to incorporate these two presences in dynamic ways. For example, I created weekly video lectures to guide students through each weekly lesson. However, the lectures were perfunctory and my delivery was robotic, serious, and tentative—a stance in contradistinction to my face-to-face teaching presence. Before the pandemic, I had never video- or audio-recorded a course lecture. I needed time to develop a level of comfort with the technology so that my delivery would reflect the embodied verbal and non-verbal cues my in-person teaching (spirit) would have readily communicated. Further, not only was my teaching presence not dynamic, but the design and implementation of the module was very teacher focused. Even when I attempted to create student-focused spaces, they were still initiated by me and reflected my ideas of what students might wish to discuss.

Nonetheless, many students persisted. One place in the self-paced module where student engagement surfaced was in the bonus activity discussion board spaces I set up. These extra credit tasks were designed for students to upload images of themselves engaging in various activities during our sheltered-in phase and to comment on the images of their classmates. While these bonus activities provided some interaction, what was needed were pedagogical activities that incorporated embodied and spiritual (reflective) aspects of learning into the virtual classroom space. Similar to the activities proposed by Compson (2017), learning needed to be reembodied and it needed to be spiritual, or to use a more secular term, “significant” (Fink, 2003: 7). For example, I could have hosted Zoom watching events for students who wished to lead and participate in group activities that provided an opportunity to be lazy and slow down, such as knitting, doing yoga, and sharing recipe ideas as a student community. I attempted to foster similar interactions through the discussion board asynchronously; Zoom would have allowed for synchronous and embodied interactions, even for students who were only able to watch the recorded videos later.

These three themes—mastery, motivation, and mythology—hold important insight for me in terms of understanding the ways in which my self-paced instructional module attempted to meet my WEIRD pedagogical goals. While this discussion actively reflects on, contextualizes, and critiques my pedagogical actions during this time, underlying this discussion is a great deal of compassion for myself and my ever-developing teaching practice. The first wave of the coronavirus on U.S. soil, sheltering-in, and managing grocery store and pharmacy runs, was an incredibly stressful period for all—for students and for instructors as we worked to maintain a degree of normalcy for students. With the immediacy of the initial wave of the pandemic behind us, the ongoing engagement with virtual teaching in the field of teacher education lies ahead.

Limitations

The survey provides valid insights into student well-being and pedagogical interactions, and the joint process of data analyses adds an element of trustworthiness to the results. However, this study does pose some limitations. For example, more direct and explicit questions could have been included in the survey that addressed the tensions I felt—the issues of space and place, the written and the read word, and access and engagement—and whether these tensions accurately expressed challenges students faced. While the survey results confirm somewhat the underlying assumptions that marked my initial pedagogical tensions, the assumptions themselves were never tested. It would have been useful to know to what extent these concerns were valid. Second, even though incorporating my spring semester course evaluations into the interpretation of the study results provided an added level of trustworthiness to the analyses, conducting student interviews would have provided an additional level of validation.

Despite these limitations, the thematic analysis allows for an intimate inquiry into the personal, practical, and pedagogical experiences my students faced in the shift to a virtual environment. The themes foregrounded by the analyses provide directions to me in moving forward pedagogically in virtual learning. In addition, this data provides a snapshot of a specific point in time, one filled with great uncertainty and fear. It is a reminder of the mood of this period, our response to the unknown, and our struggle to move through this opening phase of the COVID crises. It is in this spirit, that I lay bare my pedagogy in order to reflect on my actions (my tensions). I do so in a way that is systematic, allows for a pedagogically oriented shift in my practice, and “stands as an embodied testament to [my] beliefs” (Hamilton and Pinnegar, 2000: 238).

Conclusion

As teacher education moves deeper into the twenty first century, it appears virtual learning in K-12 as well as post-secondary settings will become a marked feature of our time. Our online pedagogy will need to reflect our core commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion; culturally responsive pedagogy; and being lazy and slowing down. In addition, the virtual environment should also foster in pedagogically sound ways the mastery, motivation, and mythology that pre-service teachers have come to expect of a teacher education program. Finally, while the voices within this survey reflect the very real emotions, concerns, and lived experiences of a select group of students during a very specific point in history—the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. soil—the analysis of and reflection on these experiences have opened up a space for me and presumably others to reconnect with pre-service teachers as simply undergraduate students.

Data Availability Statement

Because the data includes personal/individual disclosures by participants, it will not be shared publicly. Thematic data codes could be shared upon request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to M'Balia Thomas, mbthomas@ku.edu.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Badr Alenzi for his assistance with data analysis and Yu-Ping Hsu for her insightful discussions with me on Gagné. A final thanks to my students for their openness in sharing their lived experiences and allowing me to learn from them to become a better teacher and teacher educator.

References

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Anderson, T. (2001). Curriculum in distance education: an updated view. Change. 33, 29–35. doi: 10.1080/00091380109601824

Barton, G. M., Hartwig, K. A., and Cain, M. (2015). International students' experience of practicum in teacher education: an exploration through internationalisation and professional socialization. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 149–163. doi: 10.1177/1028315318786446

Berry, A. (2007). Reconceptualizing teacher educator knowledge as tensions: exploring the tension between valuing and reconstructing experience. Stud. Teach. Educ. 3, 117–134. doi: 10.1080/17425960701656510

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 12, 67–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 297–298. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Coia, L. (2016). “Trust in diversity: an autobiographic self-study,” in Enacting Self-Study as Methodology for Professional Inquiry, eds D. Garbett, and A. Ovens (Herstmonceux: SSTEP), 311–316.

Compson, J. (2017). Cultivating the contemplative mind in cyberspace: field notes from pedagogical experiments in fully online classes. J. Contemplative Inq. 4, 107–127.

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (1988). Teachers as Curriculum Planners. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Coppola, N. W., Hiltz, S. R., and Rotter, N. (2002). Becoming a virtual professor: pedagogical roles and ALN. J. MIS 18, 169–190. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2002.11045703

Cruickshank, K. (2004). Towards diversity in teacher education: teacher preparation of immigrant teachers. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 27, 125–138. doi: 10.1080/0261976042000223006

Dunn, M., and Rice, M. (2019). Community, towards dialogue: a self-study of online teacher preparation for special education. Stud. Teach. Educ. 15, 160–178. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2019.1600493

Dunstan, S. B., and Jaeger, A. J. (2015). Dialect and influences on the academic experiences of college students. J. Higher Educ. 86, 777–803. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2015.0026

Evmenova, A. (2018). Preparing teachers to use universal design for learning to support diverse learners. J. Online Learn. Res. 4, 147–171.

Fenner, D. S., and Snyder, S. C. (2017). Unlocking English Learners' Potential. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Fink, L. (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fiock, H. S. (2020). Designing a community of inquiry in online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 21, 136–153. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

Gagné, R. M. (2000). “Contributions of learning to human development,” in The Legacy of Robert M. Gagné, ed R. C. Richey (Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information and Technology), 37–80.

Gagné, R. M., Wagner, W., Golas, K. C., and Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of Instructional Design, 5th Edn. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth. doi: 10.1002/pfi.4140440211

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. J. Asynchronous Learn. Networks. 11, 61–72. doi: 10.24059/olj.v11i1.1737

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education model. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hamilton, M. L., Hutchinson, D., and Pinnegar, S. (2020). “Quality, trustworthiness, and S-STTEP research,” in International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, eds J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guð*jónsdóttir, and L. Thomas, (Singapore: Springer), 299–338. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6880-6_10

Hamilton, M. L., and Pinnegar, S. (1998). “Reconceptualizing teaching practice,” in Reconceptualizing Teaching Practice: Self-Study in Teacher Education, ed M. L. Hamilton (London: Falmer Press), 1–4.

Hamilton, M. L., and Pinnegar, S. (2000). On the threshold of a new century: trustworthiness, integrity, and self-study in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 51, 234–240. doi: 10.1177/0022487100051003012

Han, H. S., Vomvoridi-Ivanović, E., Jacobs, J., Karanxha, Z., Lypka, A., Topdemir, C., et al. (2014). Culturally responsive pedagogy in higher education: a collaborative self-study. Stud. Teach. Educ. 10, 290–312. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2014.958072

Hartman, Y., and Darab, S. (2012). A call for slow scholarship: a case study on the intensification of academic life and its implications for pedagogy. Rev. Educ. Pedagogy Cult. Stud. 34, 49–60. doi: 10.1080/10714413.2012.643740

Keengwe, J., and Kidd, T. T. (2010). Towards best practices in online learning and teaching in higher education. MERLOT: Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 6, 533–541.

Kitchen, J., and Bellini, C. (2012). Making it better for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students through teacher education: a collaborative self-study. Stud. Teach. Educ. 8, 209–225. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2012.719129

Knowlton, D. S. (2000). A theoretical framework for the online classroom: a defense and delineation of a student-centered pedagogy. N. Dir. Teach. Learn. 84, 5–14. doi: 10.1002/tl.841

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children, 2nd Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Levien, R. (2009). Immersion: A Short Fiction Film. Written and Directed by R. Levien. Produced by R. Levien, K. Fox, and Z. Poonen Levien. Available online at: http://www.immersionfilm.com/ (accessed July 27, 2020).

Lumb, P. (2016). “Muslim perspectives on racism and equitable practice in Canadian universities,” in RIP Jim Crow: Fighting Racism Through Higher Education Policy, Curriculum, and Cultural Interventions, ed V. Stead (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 77–88.

Mayuzumi, K. (2006). The tea ceremony as a decolonizing epistemology: healing and Japanese women. J. Transformative Educ. 4, 8–26. doi: 10.1177/1541344605282856

McCarty, T. L., and Lee, T. S. (2014). Critical culturally sustaining/revitalizing pedagogy and Indigenous education sovereignty. Harv. Educ. Rev. 84, 101–124. doi: 10.17763/haer.84.1.q83746nl5pj34216

Nemoto, T., and Beglar, D. (2014). “Developing likert-scale questionnaires,” in JALT2013 Conference Proceedings, eds N. Sonda, and A. Krause (Tokyo: JALT). Available online at: https://jalt-publications.org/proceedings/articles/3972-selected-paper-developing-likert-scale-questionnaires (accessed July 27, 2020).

Nieto, S. (2006). Teaching as Political Work: Learning From Courageous and Caring Teachers. The Longfellow Lecture. Bronxville, NY: Child Development Institute, Sarah Lawrence College.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: a needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educ. Res. 41, 93–97. doi: 10.3102/0013189X12441244

Pinnegar, S., and Hamilton, M. L. (2009). Self-Study of Practice as a Genre of Qualitative Research. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9512-2_4

Richey, R. C. (2000). “The future role of Robert M. Gagné in instructional design,” in The Legacy of Robert M. Gagné, ed R. C. Richey (Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information and Technology), 255–281.

Rovai, A. P. (2000). Building and sustaining community in asynchronous learning networks. Internet Higher Educ. 3, 285–297. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(01)00037-9

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Shahjahan, R. (2015). Being “lazy” and slowing down: toward decolonizing time, our body, and pedagogy. Educ. Philos. Theory 47, 488–501. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2014.880645

Tan, F., Nabb, L., Aagard, S., and Kim, K. (2010). International ESL graduate student perceptions of online learning in the context of second language acquisition and culturally responsive facilitation. Adult Learn. 21, 9–14. doi: 10.1177/104515951002100102

Thomas, M., and Carvajal-Regidor, M. (2020). “Culturally responsive pedagogy in TESOL,” in Contemporary Foundations for Teaching English as an Additional Language: Pedagogical Approaches and Classroom Applications, eds P. Vinogradova, and J. K. Shin (New York, NY: Routledge), 91–99. doi: 10.4324/9780429398612-14

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Keywords: thematic analysis, online instruction, teacher education, COVID, culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP), diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), wellness, pre-service teachers

Citation: Thomas M (2020) Virtual Teaching in the Time of COVID-19: Rethinking Our WEIRD Pedagogical Commitments to Teacher Education. Front. Educ. 5:595574. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.595574

Received: 17 August 2020; Accepted: 09 November 2020;

Published: 03 December 2020.

Edited by:

Leslie Michel Gauna, University of Houston–Clear Lake, United StatesReviewed by:

Jacqueline Joy Sack, University of Houston–Downtown, United StatesBalwant Singh, Partap College of Education, India

Copyright © 2020 Thomas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: M'Balia Thomas, mbthomas@ku.edu

M'Balia Thomas

M'Balia Thomas