Does the Son of Sam law apply to Anna Delvey's podcast?

The law, which is intended to prevent criminals from profiting from their crimes, was used against Delvey in 2019. (For those who don't remember: Delvey, whose real name is Anna Sorokin, posed as a fake German heiress. She was subsequently arrested and convicted of eight charges against her, including second-degree grand larceny. She currently remains under house arrest in her East Village apartment.)

After her assets were frozen, Delvey redistributed the money she received from Netflix for Inventing Anna to pay restitution to her victims. As she launches a podcast, The Anna Delvey Show, the question becomes: Will she have to do it again? The short answer is likely no, as her lawyers say she has paid full restitution to her victims. But let's break it down.

What is the Son of Sam law?

The law, N.Y. Executive Law § 632-a was passed in 1977 after serial killer David Berkowitz (known as the "Son of Sam") sold the rights to his story following his arrest. (The law was actually never invoked against Berkowitz.)

The law read: "An Act to amend the executive law, in relation to requiring moneys received by criminals as a result of the commission of crime to be paid to the crime victims’ compensation board for distribution to the victims of such crimes." Essentially, it prevents criminals from profiting off their crimes, instead redistributing any money received by criminals to their victims.

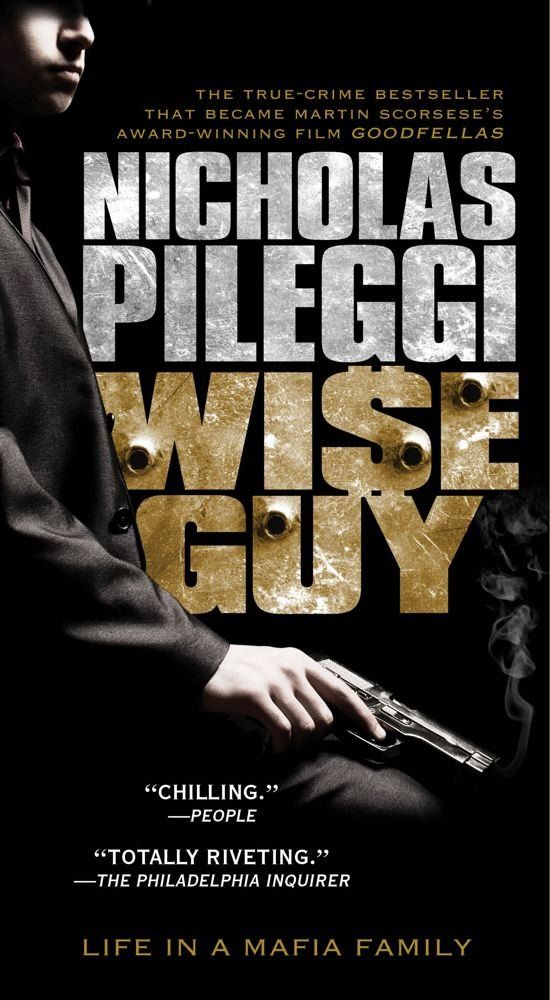

In 1987, publisher Simon and Schuster challenged New York State over the law on First Amendment grounds, as they were about to publish Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi, based on the life of Mafia associate Henry Hill. (The book would later be adapted into Martin Scorsese's GoodFellas.) In 1991, the Supreme Court held it was unconstitutional in an 8-0 decision, authored by Justice Sandra Day O'Connor. The Supreme Court noted that books like The Autobiography of Malcom X or Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau may never have been written under the "Son of Sam" law.

So does the Son of Sam Law still exist in New York?

Yes. In 2001, New York State reworked the law in an attempt to address the Supreme Court's ruling. Under the new law, a company must notify New York State's Office of Victim Services (OVS) if they plan to pay a convicted felon more than $10,000. Justin Burnworth, a lawyer and political science PhD student focusing on First Amendment constitutional law at University of Massachusetts Amherst, tells Town & Country that "the newer version is essentially the old version."

As he writes in his paper, "Making a Constitutional 'Son of Sam' Law," there were only two key changes to the new version. "First, the original law only dealt with 'profits from crimes' relating to proceeds from books, magazines, movies, or other outlets. The scope of the new law was expanded to include all 'funds of a convicted person' which includes everything from inheritances to lawsuit settlements. Second, it extended the statute of limitations to three years and the clock does not start running until the profits are discovered."

It has been sparingly applied in the 22 years since; in between 2001 and 2020, OVS froze money in 25 cases, according to the Wall Street Journal. "If you’ve been a crime victim and you’ve been through the criminal justice system, then the thought of having to pursue another case can be very daunting," Elizabeth Cronin, the director of OVS, told the Journal in 2020. "Our role is to make sure that those funds stay available until they can make that choice."

Burnworth says, "it's never [used] because these figures don't come around that often," referencing high-profile criminals who could make money off of the stories of their crime. "That's what the issue is, and that's why the Supreme Court hasn't re-addressed the issue even though that the law was changed after their decision."

New York invokes "Son of Sam" law against Delvey in 2019.

In 2019, the State of New York invoked the 'profits of a crime' part of the Son of Sam law against Delvey with regard to her Netflix deal, after Netflix notified the OVS that they had paid Delvey upwards of $300,000.

By invoking the law, Burnworth says, "it freezes the money Netflix gave her. They let everyone who she harmed know, [telling them], 'Hey, she just received a large sum of money.' Under the new law, you have three years to make your claim. She now has paid most of the money she made from Netflix in restitution to the people she harmed."

After the state invoked the law against Delvey, the OVS then froze the money that Netflix paid Delvey, and she used it to pay restitution, and to pay her lawyer. "OVS was notified by Netflix that it paid Ms Sorokin $320,000 and those funds were frozen," Janine Kava, an OVS spokesperson, told the BBC in 2021. "City National Bank filed a suit and obtained $100,000 and CitiBank did the same, obtaining $70,000. The balance of the funds must pay her attorneys' fees; any funds remaining would go to Ms Sorokin." Signature Bank, another victim, declined to file for restitution.

Still, when asked if her crime paid, Delvey told BBC Newsnight, "in a way, it did."

One of her victims, ex-friend Rachel DeLoache Williams, called out Netflix for paying Delvey. "Netflix isn’t just putting out a fictional story. It’s effectively running a con woman’s P.R.—and putting money in her pocket," Williams wrote in Air Mail. "People have never loved grift stories as much as they do today, and media companies are competing to give viewers what they want. In the case of Anna Sorokin, Netflix moved so quickly that their involvement influenced the nature of the very story they intended to dramatize."

So what happens with regard to her podcast?

Delvey just launched The Anna Delvey Show, recorded from house arrest. The official description is as follows: "Not another show about Anna Delvey. The first time audiences hear from the actual Anna Delvey. Season One is recorded from house arrest in NYC's east village. The Anna Delvey Show is a weekly podcast that explores the preconceived notions of rule breakers, effects of adversity, validity of existing systems and status quo in conversations with guests who are experts in their fields. Covering wide-ranging topics from intersections between art, politics, fashion, music, tech, film, law and finance, it will move beyond tired notions of what's right and wrong."

Might the podcast trigger the Son of Sam law? Burnworth thinks it's inevitable that it will, saying, "it would be impossible for her to do this podcast without discussing being arrested or convicted of a crime. Once she does that, the State of New York could argue that she's profiting from her crimes and then they could do the same as they did in 2019." Since her podcast is recorded as she remains under house arrest—directly part of her crime and conviction—it's hard to imagine it won't come up. Thus hypothetically, New York State could again freeze her assets and notify any victims.

Yet, it's unclear if there remain victims who could—or would—claim restitution from Delvey. A member of Delvey's legal team, Manubir S. Arora, told Town & Country, "Since the victims have been made whole, there would be no basis for a civil lawsuit regardless of whether Anna earns any money going forward."

"Anna has paid full restitution in her criminal case and served her time," Duncan Levin, another one of Delvey's lawyers, told Town & Country over e-mail. "The case is flawed and is being appealed. There is absolutely no law in New York and the United States of America that bars her from speaking about her experiences, whether she makes money or not, and we would hope the media, of all places, would respect that and understand the laws they are questioning."

Anything else?

Burnworth thinks Delvey could have a case to challenge the Son of Sam laws, "whether or not we like her position." She has a case, he thinks, because the 2001 law is so similar to the one struck down by the Supreme Court.

He also points out that there remain numerous problems with the law (which also exists in many forms in other states), specifically under freedom of speech protections. "The history of this country is that people are often charged and convicted of unjust crimes," Burnworth says, mentioning, for example, anti-drag laws that have been passed across the States.

"If someone wanted to protest [anti-drag laws], you inevitably have to break the law, in somewhere like Florida. Then, down the road, if they wanted to tell their story of going against this, the state of Florida could control the entire message," and prevent that person from ever publishing their story. (A version of the Son of Sam law does exist in Florida, Florida Statute § 944.512.)

We'll just have to wait and see what Delvey is up to next.

Emily Burack (she/her) is the Senior News Editor for Town & Country, where she covers entertainment, culture, the royals, and a range of other subjects. Before joining T&C, she was the deputy managing editor at Hey Alma, a Jewish culture site. Follow her @emburack on Twitter and Instagram.