“Cities are about life, not just about walls. The objects that we hold sacred cannot be destroyed in principle because walls and roofs constitute only one percent of their essence, the rest is sewn into the collective memory. So, don’t worry about the stones.” Iryna Isachenko, a Ukrainian journalist specializing in architecture, shared these words on Facebook in late February, days after the start of the Russian military invasion. This heartfelt sentiment resonates with other creative responses offered by Ukrainians as they grapple with the overwhelming violence and destruction of the war. Like Iryna’s reaction, these responses are often centered around material objects that stubbornly persist even after their physical demolition.

We shape our material environment, and our material environment shapes us—one does not need to be a Marxist to agree with this statement. It has become commonplace after scholars in material culture and human-thing relations such as Daniel Miller (1987, 2005) and Christopher Tilley (1999) famously argued that the taken-for-granted presence of material objects, the “humility of things,” influences our social worlds in profound ways while nevertheless evading conscious interpretation. But what happens when our material environment is violently destroyed overnight? What happens when the world of physical objects so closely entwined with our own subjective sense of self—our street, our backyard, our home, our closets, the shelf of family memorabilia—is gone or reduced to one suitcase, as millions of Ukrainians are currently experiencing? As I illustrate in this essay, Ukrainians at home and abroad are taking the ruined materiality of their lives through a process of creative reinterpretation that challenges the dichotomy between material and ideal, between ontology and signification.

With the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, I found myself in a rather uncertain position as a long-term researcher of this war. Having lived through the first active phase of the conflict in 2014-2015, I have returned regularly to conduct fieldwork in the eastern part of the country. I always considered my research as being grounded in the intimate, immediate experiences of war. On February 24, however, as Vladimir Putin unleashed a full-scale invasion and tanks rolled across the border, I found myself on the campus of Princeton University, thousands of miles away. As both a Ukrainian citizen and an anthropologist, I felt guilty, disembedded, and cut off from my community. To remain connected, I followed updates in group chats with friends and colleagues back home and kept watch of the two most popular social media platforms in Ukraine, Facebook and Telegram. Although my online engagement was personal at first, I quickly came to see these fora as important and dynamic sites worthy of ethnographic investigation. If I could not be physically present in Ukraine during this new phase of the war, I could nevertheless still witness the process of collective reflection that was taking place online.

According to the conventional wisdom of war, one should not care so much about material possessions—the only thing that truly matters is human life. However, the actual experience of war reveals that things are not so simple. Material objects matter not (or not only) because of their market value, but because they are part of us, they shape us, they carry our memories, they are affectively charged. Currently, I am observing the increasing anthropomorphism of objects and places in Ukrainian public discourse—people speak of “wounded cities” and “raped homes.” One might be tempted to think of this as a form of projection, or in other words, the displacement of one’s own feelings onto objects that are exterior to the self. But I would argue that it is something different—an extension of subjectivity. Yael Navaro-Yashin (2012) describes the intimate entanglement between people and their material surroundings in terms of the pervasive affects of haunting and melancholia that continue to be released by abandoned objects and places, even decades after their owners were expelled from Northern Cyprus. In a similar fashion, Ukrainians feel they are violated through the violation of their cities and homes, not metaphorically but quite directly. Stripped of their possessions and material environment, they find themselves in danger of being stripped of their humanity, stripped to bare life. Escaping this position requires coming to terms with the destruction and reimagining the world. This is already taking place within Ukrainian public discourse.

Sigmund Freud (1917) has described mourning as a process by which the ego gradually accepts the loss of a precious object by reframing it as existing no longer; healing may occur when the ego frees itself from these former attachments. Among Ukrainians, I argue, the work of mourning is currently being performed by means of semiosis: objects and places are being removed from the material world and placed into a symbolic universe where they acquire new meanings. Through this process, they become, according to Peircean classification, not icons or mere representations of their physical prototypes, but symbols of important abstract ideas like resilience and resistance. In the wake of both the linguistic and the material turns in anthropology, scholars have argued for the reintegration of matter and meaning, a movement that would be beneficial for cross-fertilizing studies of both. Webb Keane (2003), for instance, challenged the idea/matter dichotomy underlying the epistemic separation between the two modes of inquiry. Representations, he asserted, should be treated not as “about the world” but as “materially located within it.” The current situation in Ukraine offers an ethnographic case that illustrates such an integration.

Let us consider a couple of examples. For one, an image of a kitchen cabinet went viral in Ukrainian social media and messenger chats. The original photo portrays the insides of a bombed-out apartment building in the Kyiv suburb of Borodianka. The building is so heavily damaged that there are neither outer walls remaining, nor floor or ceiling slabs, only a blackened indoor wall, several stories high. But, by some miracle, in the middle of this wall, an almost unharmed kitchen cabinet is hanging, with some surviving plates, mugs, and spice jars still on its shelves. The casual and homely appearance of this cabinet poses a strong contrast to the scenery of brutal destruction all around it. This contrast resonated with millions of Ukrainians. The photo was instantly turned into a meme, accompanied by a series of short captions. The earliest caption read: “ –How are you, little kitchen cabinet? –Holding on.” The later versions acquired a more prescriptive tone, such as “Hold on!” and “Be strong like the kitchen cabinet.”

The photo of a surviving kitchen cabinet in a ravaged apartment building in Borodianka went viral and was turned into multiple memes calling upon Ukrainians to follow its example. Source: twitter/@agremantida; original photo by Elizaveta Servatynska.

At some point, an extra object was identified standing on top of the now-cult kitchen cabinet: a clay sculpture of a rooster, a common work of Ukrainian folk craft. In response, people began posting their own photos online showing identical roosters. Even British prime minister Boris Johnson was presented with a copy during his visit to Kyiv.

While some objects gain poignant symbolic meanings from their origins in peaceful, private, homely contexts, others are important because they are constitutive of collective identities and contribute to maintaining Ukraine as an “imagined community,” in the words of Benedict Anderson (2006). They are what was earlier referred to as “the objects we hold sacred”—churches, monuments, or, for instance, paintings of a famous Ukrainian artist Maria Primachenko heroically salvaged from a burning museum by its staff. But, arguably, the most famous case of semiotic reconstitution of such an object of collective importance is the Mriya airplane.

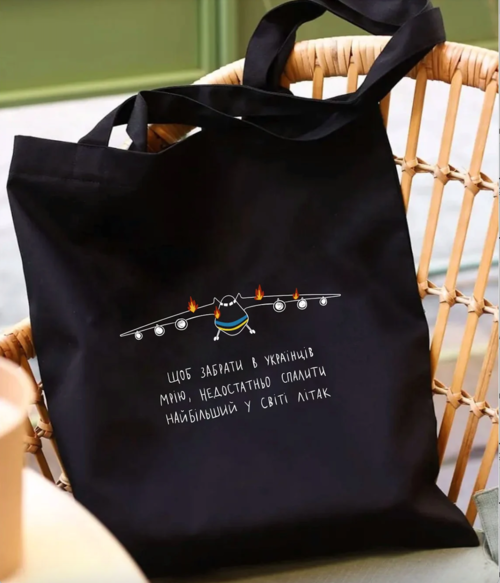

In 1988, the largest cargo airplane in the world was built in Ukraine. It was given the name Mriya (The Dream). While the practical usefulness of the cargo plane was always somewhat contested (some argued that it required too much maintenance and was quickly outdated), Mriya nevertheless figured prominently in the media and was important to Ukraine’s self-perception as a country with advanced technological capabilities and a long-standing tradition of aircraft construction. The mammoth airplane was housed in a special hangar at an airfield near Kyiv, but when the airfield was turned into a battlefield during the early days of the invasion, Mriya was ravaged in combat. It did not take long, however, for Mriya to experience a symbolic revival across social media, where it reappeared as a drawing of an airplane in flames, accompanied by the following caption: “To take the dream away from Ukrainians, it is not enough to burn down the biggest airplane in the world.”

As outside observers are horrified by the scenes of massive material destruction in Ukraine, a parallel process, an intense semiotic work of mourning, is underway inside the community and across the diaspora. The circulation of objects, from material to symbolic realms and back again, is taking place. That a rooster from atop a still-intact kitchen cabinet called forth multiple surviving copies from all over the country is but one example of such a physical return. When a destroyed object gets entrenched in the collective imagination as a meme or an otherwise publicly circulated image, it is reproduced on material surfaces, such as t-shirts or graffiti, and may take on a life of its own. No doubt, when the war is over, some of these objects will be memorialized in more formal and stable forms, as monuments or museum exhibits, and will, therefore, become formally recognized as “sacred.”

A process of creative reinterpretation is underway in Ukraine, where objects freely circulate between material and symbolic realms. Once the Mriya airplane was physically destroyed in fighting, it reappeared first in a form of a motivational drawing that went viral on social media and then, again, in material form as the drawing began to be reproduced on merchandise, in this case – on a tote bag sold by a Ukrainian vendor on Etsy. Source: etsy.com/RudnykEcoBags.

References:

Anderson, Benedict. [1983] 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Books.

Freud, Sigmund. [1917] 1957. “Mourning and Melancholia.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, edited by James Strachey, Vol. XIV: On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychol¬ogy and Other Works, 243–58. London: Hogarth Press.

Keane, Webb. 2003. “Semiotics and the Social Analysis of Material Things.” Language and Communication, 23: 409-425.

Miller, Daniel. 2005. “Materiality: An Introduction.” In Materiality, edited by Daniel Miller, 1-50. Durham: Duke University Press.

Miller, Daniel. 1987 Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Oxford: Blackwell.

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2012. The Make-believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Peirce, Charles S. 1974. “Trichotomies of Signs.” In Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vol. 2, 142-147. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tilley, Christopher.1999. Metaphor and Material Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cite As: Sopova , Alisa. 2022. ““Be Strong Like a Kitchen Cabinet”: Indestructible Objects as Symbols of Resistance in Ukraine” American Ethnologist website, 04 May 2022, https://americanethnologist.org/features/reflections/be-strong-like-a-kitchen-cabinet

Alisa Sopova is a PhD candidate in anthropology at Princeton University working on civilian lives during the war in Ukraine, from 2014 to the present. Focusing on affect, materiality, and embodied experiences of war, she seeks to recognize personal, everyday aspects of living with military violence, beyond highly ideological images of civilian populations produced by political and humanitarian actors that dominate the public discourse on war.