-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Renee Twombly, Tobacco Settlement Seen as Opportunity Lost To Curb Cigarette Use, JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Volume 96, Issue 10, 19 May 2004, Pages 730–732, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/96.10.730

Close - Share Icon Share

Tobacco settlement dollars are increasingly being used by states to shore up eroding budgets instead of for the purposes they were intended—to offset tobacco-related health care costs and institute tobacco control programs.

Congress’s investigative body, the General Accounting Office (GAO), reported in March that the 46 states party to the 1998 $206 billion Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) spent just 24% of fiscal 2003’s earnings on health programs, and the states are expected to devote even less—17%—to such programs this year.

Instead, states last year spent 36% of the $12.8 billion they collected to offset their budgets, and this year the GAO estimates that 54% of the $11.4 billion to be received will be used to address budget shortfalls.

The federal report followed closely on the heels of the 40th anniversary of the U.S. Surgeon General’s report that condemned smoking and launched a war against tobacco use, an event that has prompted soul searching among tobacco control “warriors,” as well as a little finger pointing. Whereas some see substantial progress in the war, saying smoking rates have been cut in half in the United States, others say much more should have been done by now.

Grim Numbers

The number of people who smoke, more than 46 million, is the same as in 1964 when the report was issued, critics say. They point out that between 1960 and 1990, deaths from lung cancer among women increased by more than 400% and by the mid-1980s began to exceed breast cancer deaths.

Smoking still kills more than 440,000 Americans each year and is responsible for about 90% of lung cancer and up to one-third of all cancer deaths. More than 8.6 million Americans suffer from tobacco-induced illnesses and, in fact, one in every five deaths in America is smoking related, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cigarette smoking has long been known as the single most preventable cause of premature death in the United States.

And even though public health researchers say they now know what works to curb tobacco use—comprehensive programs that include combining school, health care, community, and media anti-tobacco marketing and such policy efforts as raising taxes on cigarettes and banning indoor smoking—most states do not engage in such approaches. The few that did have substantial tobacco control programs have mostly slashed them despite the influx of MSA monies.

Many physicians and public health officials who have long been involved in trying to curb the nation’s craving for tobacco see the MSA as just one more example of how the tobacco industry has outsmarted its opponents at every turn. Others add that the public health community has relied too heavily on the expected MSA windfall and debate whether the master agreement should ever have been viewed as a vehicle to foster tobacco control.

“The tobacco industry has remained in the driver’s seat throughout the four decades since the Surgeon General’s report,” said Alan Blum, M.D., director of the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society at the University of Alabama, in a January 10 commentary in The Lancet. The money from the MSA has “been squandered, plain as day,” he said.

No Restrictions on Windfall

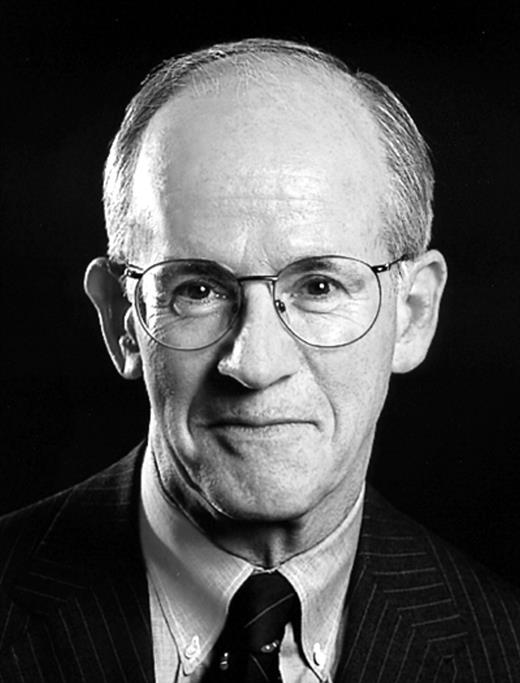

The consensus now is that “the public lost a golden opportunity to improve its health” when the MSA was approved, wrote Steven Schroeder, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, in the January 15 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Schroeder, former president and CEO of the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, said that many experts now wish the states had been more committed to tobacco control—as they said they were when the agreement was rapidly developing.

An epidemic of tobacco use among children and the burden of tobacco-related disease on state budgets were the reasons that states sued the tobacco industry in the 1990s, and why 46 of them settled for a 25-year agreement with four of the country’s largest tobacco companies in 1998. (Florida, Minnesota, Mississippi, and Texas negotiated independent agreements.)

Then, in 1999, the states asked Congress to waive its claim to the federal government’s portion of these funds. At the time, the leaders of the National Governors Association pledged to spend “a significant portion of the tobacco settlement funds on smoking cessation programs, health care, education, and programs benefiting children.” The CDC recommended that the states use at least 5% of those funds for tobacco control.

But, with the exception of the creation by the MSA of the American Legacy Foundation for public education and other tobacco control activities, there were no restrictions on the use of the funds by the states, and by October 2003, 24 states had cut their funding for tobacco prevention and cessation. Those included several of the programs that have proven most successful at reducing youth tobacco use, such as the programs in California, Massachusetts, and Florida, according to a report delivered to Congress last November by Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Myers said then that “the states lack credible excuses for their failure to do more to protect our children from tobacco. They are collecting record amounts of tobacco revenue from the tobacco settlement and tobacco taxes.”

The foundation—the big MSA tobacco control success story—is now in financial straits. Using dedicated MSA funds of about $1.7 billion, the foundation produced the “truth” campaign of counter-marketing ads, which many public health experts say is the only advertising campaign to have had a substantial effect in reducing teen smoking. But because of a “sunset” clause in the MSA, funding for the foundation is expiring.

The proviso stated that the four settling tobacco companies had to maintain a share of the domestic cigarette market of at least 99.05% to maintain funding for the foundation after its initial 5 years, said Schroeder, who also serves as chairman of the foundation. That percentage, which “was probably based on erroneous projections,” has not been met, he said.

Now, the foundation is trying to raise funds to continue its mission, and on March 16, a coalition was launched to try to retroactively close the loophole and restore anti-tobacco advertising. The group, called the Citizens’ Commission to Protect the Truth, has signed on all former U.S. Secretaries of Health, Education, and Welfare and of Health and Human Services, all former U.S. Surgeons General, and all former directors of the CDC.

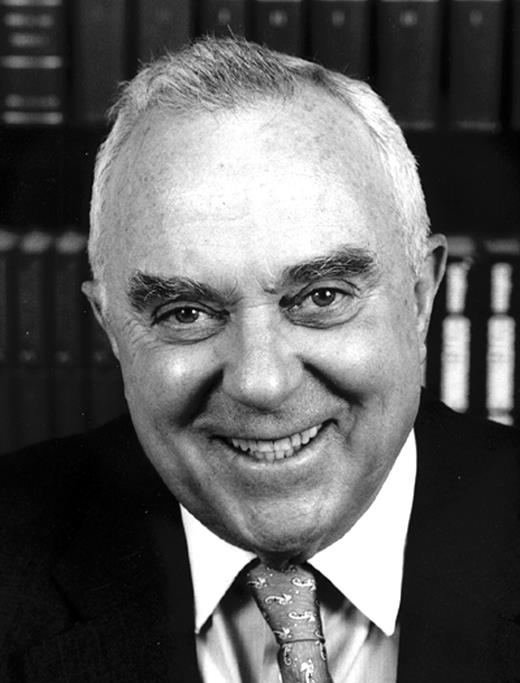

“A child who reaches age 21 without smoking, abusing alcohol, or using illegal drugs is virtually certain never to do so,” said former Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Joseph Califano Jr., chairman and president of the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. “By failing to continue funding this campaign, the tobacco companies condemn millions of children and teens to premature death and disability.”

Equally troubling to many is the fact that states are increasingly issuing bonds on future MSA payments. According to the GAO, which was mandated by Congress in 2002 to look closely at this practice, 13 of 46 states have already received substantial upfront proceeds based on the amounts that tobacco companies will owe. These bonds are backed by payments to be made in the future, and some states are tying these bonds to state tax revenues.

“These states now have a financial incentive to keep the tobacco industry healthy, because if the companies forfeit their MSA payments, the financial obligation will revert to the states,” said Schroeder. “The purpose of this money and how it is being used is one of the saddest public health stories that I have seen in the last 40 years.”

Some Gains

But others say that some good has emerged from the agreement and that, in any case, the MSA funds should never have been thought of as the answer to tobacco control.

To pay for the anti-tobacco programs required under the MSA, such as establishment of the American Legacy Foundation, tobacco companies have increased the price of cigarettes by 45 cents a pack, which has cut into the ability of young smokers to establish a habit for cigarettes, experts say. According to the National Institutes of Health, the smoking rate among young people is at a 27-year low.

The public availability of the tobacco industry documents, mandated by the MSA, has spawned an entire new area of investigation in tobacco control and has had a substantial impact on the tobacco policymaking process, both domestically and internationally, reported Stanton Glantz, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, in the February issue of the American Journal of Public Health.

“The biggest thing from the MSA is that the tobacco industry documents are on the Internet and people across the world are poring over them,” he said.

Glantz maintains there is nothing wrong with states using MSA money to plug their budgets, and the mistake lies with “the public health community viewing the funds as a kind of entitlement.

“Health groups have not done a good job of fighting for tobacco control funding on its own merits,” he said. “States should be funding tobacco control programs because of their obligation to do so, whether or not the money comes from the MSA, but it should be the public health community that pushes them to do it. The problem from the beginning is that they are unwilling to go to the wall for tobacco control.”

Blum agrees with that notion, saying that the inability to curb cigarette use “represents the worst public health failure in history.” But he argues that government money should not be used in the war on tobacco because it will never succeed due to the political influence of the tobacco industry. What is needed, he said, is to fan the flames of grassroots activism, the kind of movement that led to the indoor smoking ban.

Joseph Califano Jr.

Dr. Steven Schroeder