-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Brandon Bolte, The Puzzle of Militia Containment in Civil War, International Studies Quarterly, Volume 65, Issue 1, March 2021, Pages 250–261, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab001

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In most contemporary civil wars, governments collude with non-state militias as part of their counterinsurgent strategy. However, governments also restrict the capabilities of their militia allies despite the adverse consequences this may have on their overall counterinsurgent capabilities. Why do governments contain their militia allies while also fighting a rebellion? I argue that variation in militia containment during a civil war is the outcome of a bargaining process over future bargaining power between security or profit-seeking militias and states with time-inconsistent preferences. Strong states and states facing weak rebellions cannot credibly commit to not suppressing their militias, and militias with sufficient capabilities to act independently cannot credibly commit to not betraying the state. States with limited political reach and those facing strong rebellions, however, must retain militia support, which opens a “window of opportunity” for militias to augment their independent capabilities and future bargaining power. Using new data on pro-government militia containment and case illustrations of the Janjaweed in Sudan and Civil Defense Patrols in Guatemala, I find evidence consistent with these claims. Future work must continue to incorporate the agency of militias when studying armed politics, since these bargaining interactions constitute a fundamental yet undertheorized characteristic of war-torn states.

En la mayoría de las guerras civiles contemporáneas, los gobiernos colaboran con los grupos paramilitares no estatales como parte de su estrategia contrainsurgente. Sin embargo, los gobiernos también limitan las capacidades de sus aliados paramilitares a pesar de las consecuencias adversas que esto pueda tener en sus capacidades contrainsurgentes en general. ¿Por qué los gobiernos contienen a sus aliados paramilitares mientras luchan contra una rebelión? Sostengo que las variaciones en la contención de los grupos paramilitares durante una guerra civil son el resultado de un proceso de negociación sobre el futuro poder de negociación entre la seguridad o los grupos paramilitares que buscan beneficiarse y los estados con preferencias que son incoherentes con la época. Tanto los estados fuertes como los que se enfrentan a rebeliones débiles no pueden comprometerse a no reprimir a sus grupos paramilitares de manera convincente, y los grupos paramilitares con las capacidades suficientes para actuar de manera independiente no pueden comprometerse a no traicionar al estado verazmente. No obstante, los estados con un alcance político limitado y aquellos que se enfrentan a rebeliones fuertes deben conservar el apoyo de los grupos paramilitares, lo cual otorga una “oportunidad” para que los grupos paramilitares aumenten sus capacidades de independencia y su futuro poder de negociación. A través del uso de nuevos datos sobre la contención de los grupos paramilitares a favor del gobierno e ilustraciones del caso de los yanyauid en Sudán y las Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil en Guatemala, encuentro evidencia que es coherente con estas afirmaciones. Las futuras obras deben continuar incorporando la agencia de los grupos paramilitares al estudiar la política armada, ya que estas interacciones de negociación constituyen una característica fundamental pero poco teorizada de los estados asolados por la guerra.

Dans la plupart des guerres civiles modernes, les gouvernements s'entendent avec des milices non-étatiques dans le cadre de leur stratégie de contrinsurrection. Toutefois, ces gouvernements limitent également les capacités de leurs alliés des milices malgré les conséquences néfastes que cela peut avoir sur leurs capacités globales de contrinsurrection. Pourquoi les gouvernements endiguent-ils leurs alliés des milices tout en combattant dans le même temps la rebellion ? Je soutiens que la variation de l'endiguement des milices lors d'une guerre civile résulte d'un processus de négociation du futur pouvoir de négociation entre les milices de sécurité ou en quête de profits et les États dont les préférences sont inconstantes dans le temps. Les États puissants et les États confrontés à de faibles rebellions ne peuvent pas s'engager, de manière crédible, à ne pas éliminer leurs milices, et de même, les milices disposant de capacités suffisantes pour agir indépendamment ne peuvent pas s'engager, de manière crédible, à ne pas trahir l’État. Cependant, les États disposant d'une envergue politique limitée et les États confrontés à de puissantes rebellions doivent conserver le soutien de leurs milices, mais cela ouvre une « fenêtre d'opportunité » permettant potentiellement aux milices d'accroître leurs capacités d'indépendance et leur futur pouvoir de négociation. Je me suis appuyé sur de nouvelles données sur l'endiguement des milices pro-gouvernementales et sur des illustrations de cas des Janjawids au Soudan et des Patrouilles de défense civile au Guatemala et j'y ai décelé des preuves coïncidant avec ces affirmations. Les travaux futurs devront continuer à intégrer l'intervention des milices dans l’étude des politiques armées, car ces interactions de négociation constituent une caractéristique fondamentale mais sous-théorisée des États déchirés par la guerre.

Introduction

In the early 1980s, indigenous villagers and coca farmers in Peru banded together to form self-defense militias called rondas campesinas to defend against Sendero Luminoso attacks. Armed only with rock slings, pikes, and homemade rifles, the rondas were remarkably effective at rooting out insurgents. Despite their operational value, the Peruvian military insisted that the rondas remain a weak auxiliary force because it feared a peasant uprising (Fumerton 2001). President Fujimori eventually convinced the military to grant them a limited supply of World War I–era Mausers, but in most villages only about one-ninth of the militiamen were allowed to carry them, and all weapons were registered and closely monitored by military officials (Fumerton 2001).

Pro-government militias (PGMs) have been integral parts of counterinsurgency campaigns in the vast majority of contemporary civil wars (Stanton 2015), but failing to keep allied armed groups contained could backfire on the state if the groups could gain more by opposing the state than fighting for it (Seymour 2014; Otto 2018). Recent work acknowledges the risk of agency loss when employing PGMs (Carey, Colaresi, and Mitchell 2015), that the interactions between governments and militias have long-term implications for state-building (Ahram 2011; Reno 2011), and that state-building considerations broadly affect how states manage armed militias (Staniland 2015). However, bargaining between governments and militias over acceptable levels of armed activity constitutes a process fundamental to the character of war-torn states that has, until now, remained theoretically underspecified and empirically unaddressed.

In this study, I focus on a specific type of interaction between the state and its militia allies during civil war, which I refer to as militia containment. I define containment as an effort by the state to limit an agent's future bargaining power, thereby reducing the agent's ability to engage in future undesirable actions. In the context of militia politics during civil war, containment takes the form of restricting the militia's ability to independently use coercive force. Highly contained militias, in this sense, are easier for states to control or terminate when they are no longer useful or become threatening, but these groups will also be less powerful counterinsurgent forces during a war. Militias with greater autonomous capability, on the other hand, may be more effective anti-rebel allies, but may also be more difficult to manage, control, or terminate. Thus, whereas counterinsurgent militias and their relationship with the state are a function of the state's needs during a war, these short-term needs can have important consequences for the state's ability to consolidate power and provide a sustainable peace. As Reno (2011, 244) observes in the context of post–Cold War Africa: “the appearance of armed factions associated with past and present governments, conceived in part as instruments to bolster these governments, came to be the principal threat to their security.”

The puzzle of militia containment is two-sided: given the immediate threat faced by a rebellion, why would governments keep their non-state allies contained? At the same time, given the ex post risk of political instability, betrayal, and a reduced ability to control or demobilize unruly auxiliary forces, why should states grant significant ex ante bargaining power to militias even if they are contemporary allies? I argue that PGM containment is the outcome of a bargaining process over future bargaining power characterized by mutual commitment problems. Strong states and governments fighting wars against weak rebels cannot commit to not eliminating a militia ally if it outlives its usefulness or represents a future threat to the state. A PGM cannot commit to remaining loyal unless it has little capacity to act independently of the state's interests. When rebel threats are severe or the state's political reach is weak, the militia has incentives to demand greater autonomous capacity, and the government has incentives to acquiesce. However, when the state is strong or the rebel threat is weak, a government may credibly threaten to terminate its PGMs unless the PGM accepts its status as a contained, low-capacity auxiliary. Using new data on PGM operational containment during civil wars and an in-depth analysis of two cases, I show that counterinsurgent PGMs are more likely to be contained when rebels are relatively weak or when the state has significant political reach within its borders.

This article makes multiple important contributions to the militia politics literature. First, I develop an argument using a bargaining framework that incorporates the short-term and long-term interests of both the state and the militia. By framing militia containment in this way, I build on recent conceptual work that implies that militias are not passive actors, but rather active participants in a fluid political relationship governed by violence or credible threats thereof (Staniland 2017). The implications of militia agency are fundamental to how states choose to interact with them. Recognizing this fact is often overlooked in extant research on PGMs, but given the relational nature of armed politics, failing to account for it will lead to incomplete theory. Second, while most research on PGMs has focused on the de jure linkage between the group and the state—that is, whether the state officially recognizes its relationship with the militia (Carey, Mitchell, and Lowe 2013)—I explore their de facto interactions—namely efforts by the principal to restrict the future bargaining power of its agents. Some conceptual work has focused on how states manage violent groups (Staniland 2015), but this is the first large-N empirical investigation of patterns in PGM containment. Finally, I develop a new measure of militia containment. These data are an important step forward for future work on civil–military relations, violence management strategies, and post-conflict peacebuilding processes.

Militias and Violence Management in Civil War

Militia activity both within and outside of civil wars is so ubiquitous that the very definition of a militia is often ambiguous (Carey, Mitchell, and Lowe 2013; Jentzsch, Kalyvas, and Schubiger 2015; Carey and Mitchell 2016; Raleigh 2016).1 Efforts to categorize different types of militias have revealed that these groups can be used for a variety of purposes, including the avoidance of accountability for human rights atrocities (Carey, Colaresi, and Mitchell 2015), competition for power during democratization processes (Raleigh 2016), repression (Mitchell, Carey, and Butler 2014), coup-proofing (Carey, Colaresi, and Mitchell 2016), and as counterinsurgent supplements to regular forces during civil war (Peic 2014; Jentzsch, Kalyvas, and Schubiger 2015; Stanton 2015; Carey and Mitchell 2016).

PGMs specifically organized for combatting rebels can aid the state in different ways. At the very least, counterinsurgent PGMs provide supplemental forces that are easy to train and equip (Peic 2014; Carey and Mitchell 2016). Strong militaries without needs for additional troops can also benefit from delegating tasks to PGMs. Locally recruited militias, for instance, can provide important intelligence and help reduce rebel identification problems, which is particularly important against guerrilla insurgents (Kalyvas 2006; Lyall 2010; Clayton and Thomson 2016). These groups may abuse their newfound power against local rivals, but their ability to control populations and hold territory can be fundamental to a state's ability to defeat a rebellion (Kalyvas 2006). Some states also frame PGM membership as a symbol of national identity and signal to the broader populace that many citizens are willing to fight and die for the state (Bateson 2017). In other cases, governments refrain from acknowledging any linkage with a militia in order to retain plausible deniability for human rights violations (Mitchell, Carey, and Butler 2014; Carey, Colaresi, and Mitchell 2015). These de jure “informal” relationships allow governments to avoid domestic and international accountability costs for their actions while still using repressive violence to deter civilian participation in the rebellion.

Counterinsurgent PGMs often serve multiple purposes simultaneously, and their activities and structures can change over time. The institutional remnants of the Civil Defense Patrols in Guatemala have protected many local communities from drug cartels since the end of the civil war (Jentzsch, Kalyvas, and Schubiger 2015). The Basij militia in Iran was originally mobilized to fight in the Iran–Iraq war, but has since been reorganized and now mainly suppresses domestic dissent. Nevertheless, curtailing militia allies that originally filled a government's needs during war can be challenging (Ahram 2011). The trajectory of a militia's evolution and eventual fate is contingent upon its relationship with the state and the extent to which the state can guide and exercise control over it.

In fact, allowing militias to operate on the state's behalf can backfire if the state does not properly manage them. Militias may shirk responsibilities or switch sides entirely, especially when there are material inducements to do so, state capacity is weak, the militia organization is sufficiently cohesive, or it has rivalries with other groups (Seymour 2014; Otto 2018). This is important because if independently powerful militias can profit from ongoing war, their shifting loyalties can alter the balance of power, spoil peace negotiations, and increase the probability of war recurrence (Steinert, Steinert, and Carey 2019) or state failure (Reno 2011). States must therefore devise strategies to reduce the risk of militia betrayal ex post. When multiple militias exist simultaneously, states can leverage support for rival groups to manipulate others and hold them accountable for agency slack (Salehyan 2010; Ahram 2011). More generally, Staniland (2015) argues that if the state is motivated to eliminate the group, it can forcibly suppress it or incorporate it into formal politics. If the militia is operationally useful, the state can “collude” with the group or “contain” it by keeping its activity below an acceptable threshold.

I build on this work by investigating why governments sometimes contain militias with which they also collude. I depart from Staniland's (2015) conceptual framework in at least two ways. First, while Staniland (2015) contends that governments only contain militias that are not operationally valuable, I show that in the context of civil wars, where militias are typically very useful to the state, governments often use a containment strategy as a preemptive measure to control interactions after that usefulness is spent. Second, Staniland (2015, 780) claims that containment is a “default” strategy used for militias with an “indeterminant” role in the state's ideological project. I argue that governments not only contain their militias to varying degrees, but that this variation can be explained as a bargaining outcome.

Conceptualizing Militia Containment

States and militias often have different interests. Just because their efforts align in a fight against a rebellion does not mean that the strategic partnership between a state and its militia agents equates to “a relation of full subservience” (Kalyvas 2006; Jentzsch, Kalyvas, and Schubiger 2015, 759). During a civil war, the state and militia mutually benefit from cooperation: militias can increase the probability of government victory (Peic 2014), but these groups may also be motivated by ideology, material gains, or community protection from the state in the future. Tacit or direct support from the state can provide militia organizations the resources they need to achieve these goals (Salehyan 2010), even if they are incompatible with the long-term goals of the state (Ahram 2011; Staniland 2015). Under these conditions, contemporary support for a militia organization can translate into relative gains in the militia's future bargaining leverage, especially when these resources can improve the group's independent coercive power.

Given the risks associated with supporting or cooperating with militias, states often have strong incentives to limit their militias’ future bargaining power. I refer to this phenomenon as militia containment, which I define as an effort by the state to limit an agent's future bargaining power, thereby reducing the agent's ability to engage in future undesirable actions. The most effective way to restrict the bargaining power of a militia is to limit its ability to use coercive force. I refer to the ability to project power independent of the interests of, or constraints imposed by, another actor as autonomous capacity. A contained militia group has limited autonomous capacity because it has little leverage to pursue independent goals that do not align with those of the state.

Militia containment is a type of de facto interaction between states and militias because it involves a choice by the state to directly intervene in the ability of a militia to operate. Other types of de facto interactions and militia management strategies are explored elsewhere (Staniland 2015, 2017), but they are all conceptually distinct from de jure relationships between states and militias, such as whether a militia's linkage with the government is informal (officially covert) or semiofficial (publicly acknowledged) (Carey, Mitchell, and Lowe 2013).2De facto interactions, on the other hand, are the product of an implicit or explicit bargaining process between armed actors that are seeking to establish a relational order within the state (Staniland 2017). Containment is but one way that states can exert control over a militia and retain relative bargaining power for future interactions.

States use militia containment as a preventative strategy to maintain a power asymmetry over the group, thereby allowing the state to guide and control the militia's activity, evolution, and eventual termination. Importantly, uncontained militias are more difficult to reign in later on because they have greater bargaining leverage and therefore capability to resist unwelcome incursions from the state. These groups may therefore be less likely to become contained than contained militias are to become uncontained after changes in the conflict dynamics discussed below. Contained militias, on the other hand, have little relative bargaining leverage vis-à-vis the state because they cannot credibly threaten the state and its interests. The trade-off for the state is that these militias’ maneuverability and capabilities to fight insurgents will be more limited (Carey and Mitchell 2016). States may take into account the specific tactical purpose of the militia when deciding on its containment strategy as well as preliminary perceptions of a militia's goal variance, but I argue that considerations about future interactions and the nature of the post-war order are the primary reasons states choose to contain their own militia allies.

Bargaining, Credible Commitments, and PGM Containment in Civil War

Militias are active both within and outside of civil wars, but I focus on counterinsurgent militias for two reasons. First, these groups are often organized differently from militias that are active during peacetime (Raleigh 2016; Böhmelt and Clayton 2018). The incentives for states to contain militias in the absence of a rebellion, furthermore, are different from their incentives to contain them during war. Second, war creates unique incentives for governments to interact with militias, and these incentives change after a war has ended. Hypothetical post-war considerations enter a government's calculation when pursuing a militia management strategy during a civil war, but active rebellion represents a distinct short-term threat that must be dealt with first. In this context, I assume that both states and militias are the main actors3 and that each side can learn about the other's preferences and capabilities through repeated interactions.

Given concerns about agency slack and the post-war order, states must weigh the long-term consequences of allowing militias greater autonomous capacity against the fact that uncontained groups may be more effective at combatting a rebel threat (Carey and Mitchell 2016). States then identify the degree to which containing militia allies is optimal and then the PGM can choose to accept its status as an allied partner of the state or betray the state in some way. If a militia acquiesces to the state's preferred containment level, the state can still betray the militia by forcibly suppressing it or reneging on promises to provide the militia with a fraction of the spoils of war. The interaction between a government and its militia allies thus takes the form of a strategic bargaining process over the payoffs from victory and, most importantly, future bargaining leverage (Fearon 1996) to assure those benefits are “appropriately” dispersed. This implicit bargaining process is derived from strategic logic and expectations of the other actor's behavior, though it can manifest more concretely through formal negotiations or behaviors meant to pressure the other party and signal expectations for future actions.

The dilemma faced by both parties is that under certain conditions the other actor cannot credibly commit ex ante to avoid betraying the other in the future. Two factors can moderate this problem of credible commitment: the strength of the rebel threat and the political reach of the state. Militias can only commit to not betraying the state when they have little autonomous capacity. A government can only commit to not suppressing a militia group when it has little political reach or the current rebel threat is severe. I examine each of these factors in turn.

Rebel Threat

When a rebellion is relatively strong, the regime's immediate and existential objective is to eliminate the rebel threat. This creates strong incentives for the state to retain the loyalty and support of allied militias, increasing the likelihood that it will acquiesce to their demands. Short-run appeasement can help facilitate cooperation against a mutual rebel threat. At the same time, the local intelligence, increased operational capabilities and mobility (Carey and Mitchell 2016), and repressive capacity that a PGM can provide may prove essential for the government to succeed in the war effort. In any case, limiting the group's activities in the short run risks a defeat in the war, after which the government would not be able to accomplish its long-term state-building project. This gives the state a vested interest in not containing—and often augmenting—a militia agent's autonomous capabilities even at the expense of future bargaining leverage.

Severe rebel threats, therefore, force the government to discount the ex post risks of militia activity in exchange for a higher probability of victory. The government's short-term commitment to not forcibly eliminate the militia during the war is thus credible when the strength of the rebel threat is high. The PGM, therefore, does not face a short-term threat from the state, but states have time-inconsistent preferences across the civil war and post-war periods. Knowing that commitments made by the government during a war will not necessarily be credible after the war has ended, the PGM has incentives to take advantage of the state's short-run willingness to acquiesce. Within this window of opportunity, the PGM should demand greater autonomous capabilities, which can be used to more effectively combat the present rebellion and protect its material and political interests after the war has ended. Since the government will be unlikely to suppress the militia during the war, and because the short-run interests of the state and the militia align (i.e., defeat the rebels), the government will not seek to contain the militia, and the militia will have a higher level of autonomous capability despite the fact that this will translate to greater bargaining leverage in the future.

When the rebel threat is weak, the government still benefits from the militia's contributions to the war effort; however, it also cannot commit to not eliminating the group altogether or reneging on promises to provide some fraction of post-war payoffs. The state, having a lesser need for an independent, highly capable militia to defeat the rebels, can certainly not only gain from the intelligence gathering and tactical advantages of employing the militia, but can also keep the militia weak by restricting its autonomous capabilities. Containing militia allies is optimal for a government fighting weak rebellions because it can later suppress the militia if or when it outlives its usefulness. By restricting the militia's autonomous capabilities, the state can punish the group for improprieties or disloyalty, reorganize or terminate the group when it is no longer needed for security purposes, or preserve the payoffs from victory for itself.

Faced with this “offer,” the militia can remain an organized entity but with limited autonomous capabilities or it can demand more in the hopes of defending itself and its interests against the state in the future. Though the PGM would be better off in the long run if it had greater autonomous capability, its bargaining leverage to attain these capabilities is limited because the government has few constraints that would prevent it from eliminating the group. If the government anticipates that the militia desires to increase its capabilities or dissent from the state's interests, the threat imposed by the rebels will do little to keep the government from suppressing the militia that could pose an additional threat in the future. The militia, then, should be more likely to consent to being contained and to operate loyally. The militia will have some ability to defend a community it represents or to obtain material resources for its members, and by accepting its contained status, the militia can also commit to not egregiously betraying the state. The state, therefore, has little reason to fully suppress the militia when the rebel threat is weak. Instead, the militia will actively participate in the civil war, but it will be contained: (H1) when a rebellion is more (less) threatening to the government, PGMs will be less (more) contained.

Internal Political Reach

The political and social dimensions of a state's embeddedness in society are fundamental to its capacity to maintain security. States with greater political reach are characterized by higher levels of authoritative capacity in all corners of the country, not only because of efficient administrative infrastructure, but also because the state's presence is accepted by the population in its day-to-day activities (Arbetman-Rabinowitz et al. 2012). States with more limited political reach have fragmented, vertically disengaged political influence over their territory (Rotberg 2004) as well as an inability to mobilize assets or human resources to accomplish political goals (Arbetman-Rabinowitz et al. 2012). During a civil war, the extent of a state's internal political reach is also important in determining the credibility of its commitments when bargaining with armed militias.

When a state has low political reach, employing militias becomes crucial for countering an insurgency. Even if these states have large militaries, their ability to use coercive force in all parts of the country is limited (Rotberg 2004). Deploying official counterinsurgent forces to peripheral areas is challenging because local administrative institutions are disconnected from the state (Boone 2003) and local populations are more wary of the state's role in their lives. This security problem is amplified if rebels have already established deep social roots in these territories (Kalyvas 2006). Since combatting rebels is more difficult for official security forces when the state has limited political reach, governments must retain the loyalty of militias by appeasing their interests if they wish to neutralize their armed opposition.

Beyond their incentives to retain the support of armed militias, governments with limited political reach often share more short-run interests with them. When rebels tread on militia territory, both the government and the militias will want to eliminate the rebellion. If a government contains its militia allies, it will restrict their abilities to project force against a rebel group, thereby hindering their efforts to defeat a shared enemy. Governments with little political reach, therefore, will not only avoid containing their militias, but they may also actively grant them greater autonomous capacity.

Finally, the fact that states with low political reach have limited administrative authority and presence across their territories means that efforts to contain militia allies are particularly costly. Indeed, governments with little coercive capacity “are unlikely to expend it all on groups that are seen as a mild political challenge, even if these groups are large, wealthy, or well-armed” (Staniland 2015, 780). Efforts to monitor militias in peripheral regions are impeded by spatial and political distance, and threats to punish disloyalty ex post are therefore not credible. Governments with limited political reach should be more likely to expend their limited resources on fighting the rebellion directly rather than containing their own non-state allies.

These three reasons—the importance of retaining militia loyalty, incentives to grant them autonomous capabilities to combat the rebels, and the relatively high costs associated with containing militias—all imply that low political reach makes commitments to not suppress a militia during a civil war more credible. This, in turn, leads to cooperative efforts between governments and militias during the civil war, wherein governments will concede greater autonomous capacity to militias even if this adversely affects future bargaining, and militias will happily maximize their autonomous capabilities to defend against rebels and acquire greater future bargaining leverage against the state.

In states with significant political reach, however, the government cannot credibly commit to not eliminating militia allies in the future. The state is far more embedded in society, both socially and administratively (Boone 2003; Rotberg 2004; Arbetman-Rabinowitz et al. 2012), which moderates its reliance upon militias for local information and tactical support. Moreover, states with greater political reach can more easily access various regions within the country to project coercive force against rebels without the support of militias or against militias if they threaten to betray the state. This is not to say that states with high political reach have no need for counterinsurgent PGMs: even strong states can gain from local intelligence and increased repressive capabilities. These states, however, are often not dependent on militia support during a civil war if the long-term risks of militia activity are too great. Finally, states with greater political reach can more effectively and efficiently mobilize human resources to achieve policy goals (Arbetman-Rabinowitz et al. 2012). Although this is primarily important for allocating economic resources in most states, states embroiled in civil war can use their administrative apparatus to mobilize recruits or repress a militia if necessary. These features of states with high political reach all suggest that these states cannot credibly promise ex ante to not suppress a militia or renege on promises to it.

In this context, a militia can demand greater autonomous capacity, but since the militia is less operationally useful and the government can more easily suppress it, demands that affect future bargaining power will invite the state to eliminate the militia altogether. If the militia accepts its status as a contained ally of the state, it can credibly commit to not betraying the state because it has little capability to do so while still retaining some capability to resist the rebels. The state can then confidently utilize the militia to enhance its operations against a rebellion and the militia will be contained: (H2) PGMs will be more (less) contained in states with greater (lesser) political reach.4

Although I focus on the dyadic interaction between a state and a militia, in many civil wars multiple PGMs are active. Research on principal–agent relationships has shown that principals “can construct checks and balances where multiple agents are created to increase competition among one another, reveal information about opportunistic behavior, and mitigate agency slack” (Salehyan 2010, 502). Manipulating “competing agents” can be another useful militia management strategy, particularly in weak states whose repressive capabilities are not credible and containment is not a viable option. The presence of multiple militias may help these states credibly threaten to eliminate others if they resist containment efforts because the government can easily turn to other groups. On the other hand, this strategy can increase the risk that a militia switches sides because rivalries among the agents can become more acute (Otto 2018). This may incentivize states to contain each group to a greater degree if they are able, but states with limited political reach may be unable to do so. Under these conditions, states with weak political reach may be more likely to appease groups than contain only some. In either case, using competing agents against one another is a distinct militia management strategy from containment. Bargaining between states and multiple militias may be more complicated in these situations, but the logic I present here is relevant for conflicts with one or multiple militias.

Data Collection and Research Design

To test the hypotheses above, I collected new data on counterinsurgent PGMs in civil wars from 1989 to 2010. I defined my sample frame using the list of civil wars and active PGMs from Stanton (2016), who restricts her sample to wars with at least 1,000 battle deaths.5 To be included in my analysis, a PGM must be involved in the war effort by directly attacking rebel groups or targeting the civilian constituents of rebels in an explicit attempt to control the population or deter them from participating in the rebellion. I focus on counterinsurgent militias because existential threats to the state from a rebellion in part shape the bargaining process I propose, and that process may be different for other types of militias that are not used for anti-rebel purposes. I also exclude death squads from the analysis since they tend to be smaller groups meant for assassinations as opposed to organized groups meant for combatting insurgents. Following Stanton (2015), my units of analysis are PGM-rebellion dyads. The final sample includes 238 total dyads comprising 156 PGMs across 87 civil wars in 39 countries.

Dependent Variable

Measuring the containment of a PGM is challenging, but the concept I present is based on limiting the autonomous capacity of the militia—that is, restricting the ability of the group to act against the interests of the state in the future. A contained militia is one that has little capability to exercise its own will through the use or credible threat of force. My measure of militia containment is based on the ability of a militia to use coercive force independently of the state. To this end, my measure is centered on militia armament and restrictions on those arms.

To construct my variable, I scoured hundreds of news articles, books, academic journal articles, and reports from Human Rights Watch (HRW), Amnesty International, and Small Arms Survey to identify the weapons used by each group and roughly estimate how those weapons were distributed among the members of the group. I considered three primary pieces of information to develop my measure: (1) the types of weapons group members use in operations or patrols; (2) the prevalence of automatic weaponry or firearms among the group; and (3) any evidence that the regular military actively and systematically regulates, monitors, controls, or restricts the weaponry used by militia members. I had more precise information about each of these components for some groups than others, but by triangulating the available information I have developed a reasonably accurate measure of militia containment.

Using this information, I coded my dependent variable—Containment—as an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 3. I coded groups with a 1 (low containment) if all or the vast majority of militia members have automatic weaponry6; and/or the group regularly uses high-powered rifles, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, etc.; and there is no evidence that the government consistently and systematically restricts or monitors the militia's use of ammunition or weapons (e.g., Arkan's Tigers in Yugoslavia). I coded PGMs with a 3 (high containment) if the group uses few to no professional firearms, relying almost entirely on traditional weapons like spears, sticks, stones, knives, machetes, and bows and arrows. These highly contained, weakly armed groups may use some firearms or homemade or tribal hunting rifles, but this is limited to at most 20 percent of the group and/or these limited firearms are heavily restricted by the official military. For instance, some militia members are only allowed to carry government-issued shotguns under supervision or when on patrol but must return them to a military headquarters at night. In other cases, the military will provide limited firearms to militia members, but only allow each unit a small allotment of ammunition (e.g., pro-Indonesian militias deployed against East Timor's independence movement). Moderately contained groups (coded with a 2) are those in which most members have access to some kind of firearm, but ammunition or the weapon itself is regulated by the military; a middling portion of the militia is armed with a firearm while the rest of the members rely on other “cold weapons” in their operations; or all members of the militia are issued firearms, but these weapons are limited to old shotguns or small pistols (e.g., Guardians of Peace in Burundi). Ninety-four of the 156 groups are coded as poorly contained, and 62 groups were either moderately or highly contained.

My measure of militia containment does have important limitations. First, the measure assumes that all states have some level of control over weapons distribution. This assumption may be strong in some contexts, but a large portion of PGMs in the dataset receive most of their weapons from the government, and in many of the cases where groups armed themselves, the government had overtly encouraged local weapons procurement. More importantly, the data for my dependent variable is time-invariant. Collecting time-varying data for my dependent variable is challenging for at least three reasons. First, PGM activity levels fluctuate over time, so it is difficult to know a militia's level of arms when they are not particularly active. Second, journalists may be deterred from entering conflict zones, so public information about these groups can be uncertain. Third, states often hide their relationships with PGMs, so obtaining reliable information about armament levels and restrictions every year can be difficult. The unfortunate consequence is that my cross-sectional design cannot test the dynamic aspects of my theory. For instance, I expect that within the same conflict, governments will contain their militia agents more as rebels grow weaker and will sacrifice future relative bargaining leverage when rebels become stronger.

While the cross-sectional design is certainly a limitation, the information available about some groups as well as the ordinal nature of my coding procedure gives me confidence that it is not a severe empirical problem. Some militias have received more widespread attention than others, so I was able to anecdotally observe some changes in containment over time for a few groups. In many of these cases, temporal changes in containment were minimal (such as the rondas campesinas discussed above). Even more drastic changes typically were not enough to cross the ordinal thresholds I defined for my measure.7 Nevertheless, the data presented here represent a first systematic attempt to study militia containment and should be interpreted with caution.

Independent and Control Variables

I measure the threat posed by the rebellion with the logged ratio of government to rebel troops. The data are based on Stanton's (2016) estimates, which are drawn from The Military Balance and SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) Yearbooks and averaged across the years of the war.8 Large ratios indicate that the government is far stronger than the rebels, and thus the threat posed by the rebels is not as severe. I expect a positive relationship between Weak Rebels and PGM Containment.

To test my second hypothesis, I use Kugler and Tammen's (2012),Relative Political Reach (RPR) variable, which captures the level of actual taxable participation in the formal economy based on economic activity, bureaucratic efficiency, and population characteristics. RPR corresponds well to the dimensions of internal political reach discussed in my argument because it measures “the degree to which the government influences and penetrates into the daily lives of individuals” (Arbetman-Rabinowitz et al. 2012, 20). RPR is therefore useful for capturing the ability of a state to contain allied militias independently from its military strength. To avoid endogeneity concerns, I use the country's RPR value from the year prior to the start of the war.

I control for a variety of group-level and country-level variables. First, I control for whether the militia and rebels recruit from the Same Ethnic Group. These militias are often used for reducing rebel identification problems (Lyall 2010; Clayton and Thomson 2016), none of which require significant autonomous capability. Combined with greater fears of disloyalty or betrayal, this may lead states to keep these groups contained, all else equal. I used data from Stanton (2015) as well as various secondary sources to code my cases. Similarly, I code separate variables with a 1 if a given PGM has Peasant9 or Criminal membership (PGMD). Governments may be reluctant to empower the peasantry for fear of a future uprising, or the purpose of localized civilian defense forces more broadly (Clayton and Thomson 2016) simply does not require a government to allow the group to operate with impunity. Militias with Criminal membership may be motivated primarily by profit, which could cause them to be undisciplined or more inclined to follow profit than the state's interests. I rely on the PGMD for both these variables and filled in missing values on my own when possible.

I also control for factors that may influence the goal variance between the militia and state. Semiofficial militias, for instance, may be more closely aligned to the state's official security apparatus and therefore states may be less likely to contain them (PGMD). I also include a binary variable for whether members of the official security forces jointly serve in the militia (PGMD). Joint Membership decreases monitoring and information problems and will likely be associated with less goal variance between the state and the group.

At the country level, I control for the GDP/capita of the country (Gleditsch 2002) in the first year of the war, as well as the country's Polity score (Marshall, Gurr, and Jaggers 2014). Since weapons flows may be more difficult to contain when foreign civil wars border the country in question, I also include a binary indicator reflecting whether there is an ongoing Contiguous War. Finally, I include a count variable for the Number of Militias active in the conflict, which may influence the probability of intergroup conflict and defection (Otto 2018), as well as a binary measure for whether the rebels are Separatists.

Method of Analysis

Since my dependent variable is ordinal, the natural method of analysis is an ordered logistic regression. However, this method assumes that the first derivatives with respect to the covariates are the same across ordinal categories. Brant tests suggest occasional violations of the parallel regressions assumption, meaning that the effects of these variables are not the same across dependent variable categories.10 To estimate these differential effects, I present results from separate binary ordered logistic regressions: in the first logit, the dependent variable takes on a value of 0 if Containment is low and a 1 if Containment is moderate or high; in the second logit, the dependent variable takes a value of 0 if Containment is low or moderate and a 1 if Containment is high. I report clustered standard errors by conflict to adjust for heteroskedasticity in the error term.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 provides the coefficient estimates for the ordered binary logistic regressions. Models 1–2 only include the independent variables of interest, Models 3–4 include all PGM level controls, and Models 5–6 also include country-level controls. The dependent variable in Models 1, 3, and 5 is whether the PGM's containment level is 2 (moderate) or 3 (high), and Models 2, 4, and 6 estimate the probability of high containment only.

Ordered binary logits—levels of PGM containment

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | Model 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . |

| Troop Ratio (logged) | 0.462*** | 0.713*** | 0.532*** | 0.779*** | 0.455** | 0.957*** |

| (0.12) | (0.159) | (0.15) | (0.196) | (0.18) | (0.353) | |

| RPR | 2.817*** | 1.871** | 3.137*** | 1.983* | 3.282*** | 1.559 |

| (0.832) | (0.845) | (0.888) | (1.091) | (1.245) | (1.579) | |

| Shared Ethnic | −0.145 | −0.475 | 0.094 | −0.739 | ||

| (0.605) | (0.85) | (0.596) | (0.857) | |||

| Criminal | 0.728 | 1.909** | 0.88* | 1.988** | ||

| (0.519) | (0.859) | (0.515) | (0.971) | |||

| Peasant | 1.697*** | 2.524*** | 1.972*** | 2.364*** | ||

| (0.414) | (0.689) | (0.517) | (0.647) | |||

| Semiofficial | −1.146** | −1.428*** | −0.984 | −1.258** | ||

| (0.502) | (0.443) | (0.674) | (0.576) | |||

| Joint Membership | −1.74*** | 0.366 | −1.198** | 0.682 | ||

| (0.494) | (0.653) | (0.558) | (0.711) | |||

| Contiguous War | −1.862*** | −0.837 | ||||

| (0.466) | (0.762) | |||||

| GDP/Capita (logged) | −0.46** | −0.732** | ||||

| (0.221) | (0.328) | |||||

| Separatist | −0.062 | −0.622 | ||||

| (0.413) | (0.884) | |||||

| Polity | 0.074** | 0.05 | ||||

| (0.032) | (0.046) | |||||

| Number of Militias | 0.048 | −0.017 | ||||

| (0.056) | (0.057) | |||||

| Constant | −4.722*** | −6.635*** | −5.463*** | −7.685*** | −1.209 | −1.656 |

| (1.028) | (1.353) | (1.212) | (2.213) | (2.401) | (3.598) | |

| Observations | 212 | 212 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.234 | 0.29 | 0.329 | 0.403 | 0.419 | 0.431 |

| Log likelihood | −110.874*** | −68.571*** | −88.263*** | −54.658*** | −76.342*** | −52.096*** |

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | Model 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . |

| Troop Ratio (logged) | 0.462*** | 0.713*** | 0.532*** | 0.779*** | 0.455** | 0.957*** |

| (0.12) | (0.159) | (0.15) | (0.196) | (0.18) | (0.353) | |

| RPR | 2.817*** | 1.871** | 3.137*** | 1.983* | 3.282*** | 1.559 |

| (0.832) | (0.845) | (0.888) | (1.091) | (1.245) | (1.579) | |

| Shared Ethnic | −0.145 | −0.475 | 0.094 | −0.739 | ||

| (0.605) | (0.85) | (0.596) | (0.857) | |||

| Criminal | 0.728 | 1.909** | 0.88* | 1.988** | ||

| (0.519) | (0.859) | (0.515) | (0.971) | |||

| Peasant | 1.697*** | 2.524*** | 1.972*** | 2.364*** | ||

| (0.414) | (0.689) | (0.517) | (0.647) | |||

| Semiofficial | −1.146** | −1.428*** | −0.984 | −1.258** | ||

| (0.502) | (0.443) | (0.674) | (0.576) | |||

| Joint Membership | −1.74*** | 0.366 | −1.198** | 0.682 | ||

| (0.494) | (0.653) | (0.558) | (0.711) | |||

| Contiguous War | −1.862*** | −0.837 | ||||

| (0.466) | (0.762) | |||||

| GDP/Capita (logged) | −0.46** | −0.732** | ||||

| (0.221) | (0.328) | |||||

| Separatist | −0.062 | −0.622 | ||||

| (0.413) | (0.884) | |||||

| Polity | 0.074** | 0.05 | ||||

| (0.032) | (0.046) | |||||

| Number of Militias | 0.048 | −0.017 | ||||

| (0.056) | (0.057) | |||||

| Constant | −4.722*** | −6.635*** | −5.463*** | −7.685*** | −1.209 | −1.656 |

| (1.028) | (1.353) | (1.212) | (2.213) | (2.401) | (3.598) | |

| Observations | 212 | 212 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.234 | 0.29 | 0.329 | 0.403 | 0.419 | 0.431 |

| Log likelihood | −110.874*** | −68.571*** | −88.263*** | −54.658*** | −76.342*** | −52.096*** |

Note: Cluster-adjusted robust standard errors reported in parentheses; *p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Ordered binary logits—levels of PGM containment

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | Model 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . |

| Troop Ratio (logged) | 0.462*** | 0.713*** | 0.532*** | 0.779*** | 0.455** | 0.957*** |

| (0.12) | (0.159) | (0.15) | (0.196) | (0.18) | (0.353) | |

| RPR | 2.817*** | 1.871** | 3.137*** | 1.983* | 3.282*** | 1.559 |

| (0.832) | (0.845) | (0.888) | (1.091) | (1.245) | (1.579) | |

| Shared Ethnic | −0.145 | −0.475 | 0.094 | −0.739 | ||

| (0.605) | (0.85) | (0.596) | (0.857) | |||

| Criminal | 0.728 | 1.909** | 0.88* | 1.988** | ||

| (0.519) | (0.859) | (0.515) | (0.971) | |||

| Peasant | 1.697*** | 2.524*** | 1.972*** | 2.364*** | ||

| (0.414) | (0.689) | (0.517) | (0.647) | |||

| Semiofficial | −1.146** | −1.428*** | −0.984 | −1.258** | ||

| (0.502) | (0.443) | (0.674) | (0.576) | |||

| Joint Membership | −1.74*** | 0.366 | −1.198** | 0.682 | ||

| (0.494) | (0.653) | (0.558) | (0.711) | |||

| Contiguous War | −1.862*** | −0.837 | ||||

| (0.466) | (0.762) | |||||

| GDP/Capita (logged) | −0.46** | −0.732** | ||||

| (0.221) | (0.328) | |||||

| Separatist | −0.062 | −0.622 | ||||

| (0.413) | (0.884) | |||||

| Polity | 0.074** | 0.05 | ||||

| (0.032) | (0.046) | |||||

| Number of Militias | 0.048 | −0.017 | ||||

| (0.056) | (0.057) | |||||

| Constant | −4.722*** | −6.635*** | −5.463*** | −7.685*** | −1.209 | −1.656 |

| (1.028) | (1.353) | (1.212) | (2.213) | (2.401) | (3.598) | |

| Observations | 212 | 212 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.234 | 0.29 | 0.329 | 0.403 | 0.419 | 0.431 |

| Log likelihood | −110.874*** | −68.571*** | −88.263*** | −54.658*** | −76.342*** | −52.096*** |

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | Model 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . | (L-M/H) . | (L/M-H) . |

| Troop Ratio (logged) | 0.462*** | 0.713*** | 0.532*** | 0.779*** | 0.455** | 0.957*** |

| (0.12) | (0.159) | (0.15) | (0.196) | (0.18) | (0.353) | |

| RPR | 2.817*** | 1.871** | 3.137*** | 1.983* | 3.282*** | 1.559 |

| (0.832) | (0.845) | (0.888) | (1.091) | (1.245) | (1.579) | |

| Shared Ethnic | −0.145 | −0.475 | 0.094 | −0.739 | ||

| (0.605) | (0.85) | (0.596) | (0.857) | |||

| Criminal | 0.728 | 1.909** | 0.88* | 1.988** | ||

| (0.519) | (0.859) | (0.515) | (0.971) | |||

| Peasant | 1.697*** | 2.524*** | 1.972*** | 2.364*** | ||

| (0.414) | (0.689) | (0.517) | (0.647) | |||

| Semiofficial | −1.146** | −1.428*** | −0.984 | −1.258** | ||

| (0.502) | (0.443) | (0.674) | (0.576) | |||

| Joint Membership | −1.74*** | 0.366 | −1.198** | 0.682 | ||

| (0.494) | (0.653) | (0.558) | (0.711) | |||

| Contiguous War | −1.862*** | −0.837 | ||||

| (0.466) | (0.762) | |||||

| GDP/Capita (logged) | −0.46** | −0.732** | ||||

| (0.221) | (0.328) | |||||

| Separatist | −0.062 | −0.622 | ||||

| (0.413) | (0.884) | |||||

| Polity | 0.074** | 0.05 | ||||

| (0.032) | (0.046) | |||||

| Number of Militias | 0.048 | −0.017 | ||||

| (0.056) | (0.057) | |||||

| Constant | −4.722*** | −6.635*** | −5.463*** | −7.685*** | −1.209 | −1.656 |

| (1.028) | (1.353) | (1.212) | (2.213) | (2.401) | (3.598) | |

| Observations | 212 | 212 | 194 | 194 | 194 | 194 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.234 | 0.29 | 0.329 | 0.403 | 0.419 | 0.431 |

| Log likelihood | −110.874*** | −68.571*** | −88.263*** | −54.658*** | −76.342*** | −52.096*** |

Note: Cluster-adjusted robust standard errors reported in parentheses; *p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Models 1 and 2 provide evidence consistent with H1 and H2, since the coefficients for both independent variables are in the predicted direction and statistically distinguishable from zero at the 95 percent confidence level. The results hold after including PGM-level controls. The coefficients and standard errors both increase slightly when controlling for other PGM characteristics in Models 3 and 4, but the positive coefficients for Weak Rebels remain statistically significant at the 99 percent confidence level. A similar pattern emerges for the RPR variable, but the coefficient estimate in Model 4 is less precise. The full models with state-level controls also provide evidence consistent with H1 and H2, but RPR loses statistical significance in the high containment model (Model 6). However, after removing GDP/capita from this model (not shown), RPR regains statistical significance.

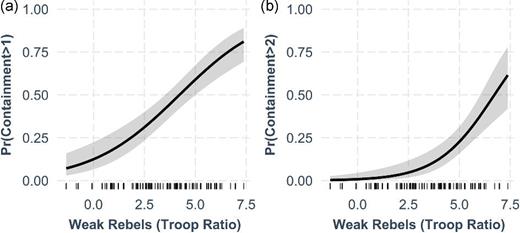

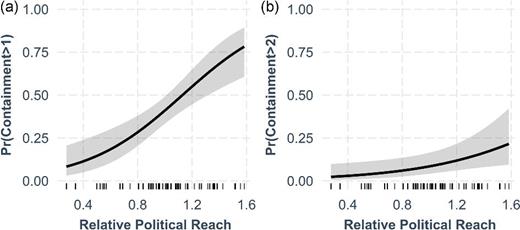

To better assess the substantive effect of rebel strength and political reach, I provide simulated predicted probabilities for each independent variable in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The values are simulated from Models 1 and 2 in order to avoid overparameterization when calculating the substantive effects. Figure 1a demonstrates that the effect of the strength of the rebel threat is not only statistically significant, but also substantively strong. When the rebels are at parity with or stronger than government forces (Troop Ratio < 0), the probability of containment is negligible, but when the government is significantly stronger than the rebels, the probability of some level of containment stretches to over 80 percent. Figure 1b depicts a similar trend, though rebel strength only seems to affect the probability of high militia containment when the rebels are particularly weak (Troop Ratio > 3). The substantive effect of RPR on the probability of any PGM containment is approximately as strong as that of relative rebel strength (Figure 2a). However, the predicted probability of high containment remains low (though slowly increasing) across all levels of RPR (Figure 2b).

The control variables also offer interesting insights. First, neither separatism nor shared ethnicity between the rebels and militia has any discernible effect on the probability of any level of containment. The Number of Militias is also statistically unrelated to containment levels, suggesting that the presence of multiple agents does not systematically influence the state's decision calculus with respect to keeping any specific militia contained. Peasant militias are more likely to be contained at all levels, which is unsurprising given that many of these groups are meant for information gathering rather than direct confrontations with rebels. Criminal membership tends to correlate with highly contained groups, but less so with the probability of containing a militia at all.

Interestingly, Semiofficial militias are associated with lower levels of containment across all models, though the coefficient is statistically insignificant in Model 5. This may be because Semiofficial militias are often used for coup-proofing (Carey, Colaresi, and Mitchell 2016) or have less goal variance from the state at the outset of their mobilization (Carey and Mitchell 2017), but more research into the association between de jure relationships and de facto interactions between states and militia agents is clearly warranted. Unsurprisingly, joint military membership and the presence of contiguous intrastate war correlate negatively with the probability of any containment, but not with the degree of containment. Wealthier countries tend to contain their militias less and democratic states appear to be more likely to contain their militias but not more likely to severely restrict them relative to autocratic states.

Overall, the fully specified models above predict in-sample cases reasonably well. The total proportional reduction in error for Model 5 is 65 percent, with 87 percent of low containment cases and 84 percent of combined moderate and high containment cases predicted correctly. The model estimating high containment relative to moderate or no containment reduces the error by 45.71 percent over the null model, with 69 percent of high containment cases and 95 percent of low and moderate cases predicted correctly.

In the online appendix, I evaluate the robustness of the results with additional model specifications and econometric methods. I also discuss and empirically evaluate the possibility of endogeneity between militia containment and my main independent variables. These supplemental analyses do not significantly alter the main results, though the results are stronger when modeling the change from no containment to at least some containment.

Case Illustrations

The quantitative analysis corroborates the patterns predicted by my bargaining framework. In this section, I discuss two cases in detail to elucidate additional empirical insights into how the bargaining dynamics discussed above occur in the real world. I first discuss the Patrullas Autodefensas Civiles (PACs) from the Guatemalan Civil War. This conflict was characterized by a moderate-to-weak rebel threat that declined through the 1980s and 1990s as well as moderate political reach that slowly increased over time. I then discuss the Janjaweed militias in Sudan, which operated in an exceptionally weak state against multiple strong rebel threats. These cases are useful illustrations of my theory because they not only vary cross-sectionally with respect to my independent variables, but also show that more nuanced shifts in containment across subnational space and time are consistent with my theory. The militias also have different de jure relationships with the state, which do not seem to be the primary driver of their containment levels; both militias were mobilized mainly through top-down processes and both conflicts had significant ethnic components and considerable levels of violence.

PACs in Guatemala

The civil war in Guatemala (1960–1996) included one of the most brutal counterinsurgency campaigns in Latin American history. In the early 1980s alone, the Guatemalan military decimated over 400 villages and slaughtered approximately 75,000 people (Remijnse 2001). In January 1982, the four main rebel groups formed a united guerrilla alliance called the Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca. One month later, General José Efraín Ríos Montt seized power in a coup and instituted an extremely violent counterinsurgency campaign designed to achieve political, economic, military, and “psychosocial stability” (Schirmer 1998). The Guatemalan military's ultimate objectives were not only to eradicate the guerrillas, but also to shift civilian psychology away from supporting the rebellion and toward a unified Guatemalan nation.

The most fundamental component of the counterinsurgent strategy was the mobilization of civil defense patrols, which would be introduced first to areas in which the intensity of conflict between the government and rebels were most severe (Schirmer 1998; Fumerton and Remijnse 2004). Mobilizing civilian patrols was not always an easy task, however. The first effort to form civil militias in the 1980s was actually in September 1981. The government attempted to forcibly recruit thousands of peasants in Huehuetenango, but the effort was poorly organized and many indigenous Mayans resisted. The state responded by razing entire villages and slaughtering their inhabitants (Schirmer 1998).

Under Ríos Montt's newly installed military administrative bureaucracy, the PAC mobilization campaign was far more systematic and efficient. Military officers would enter a village, call a mandatory gathering of the community, demand that a militia organize to root out “subversives,” and then stage elaborate swearing-in ceremonies with a recitation of patriotic songs, oaths of service, and photographs for the press (Americas Watch [AW] 1986). Most civilians were hesitant to participate in the patrols either because they wanted to avoid being targeted by the rebels or because they actively supported them. For this reason, the government demanded that all males aged 18–60 must participate and adhere to a code of conduct, which included pledges to “support the Guatemalan Army in all its actions” and “not misuse the arms and ammunition given to me” (AW 1986, 99). By the end of 1982, as many as 300,000 patrollers were mobilized across 850 villages, subsequently growing to as many as 1.3 million—or 16.87 percent of the country's population—in the next few years (Schirmer 1998; Bateson 2017).

A few communities already had civil patrols established prior to Ríos Montt's PAC program, but these communities used them to defend themselves against violence and implement local justice independently from the state. This exercise in local autonomy—even when it was used against the insurgents—was unacceptable to the Guatemalan military regime. In Nahualá, for instance, a civil defense force formed after rebels had attacked local residents. According to an interview conducted by Americas Watch (1986):

In 1982, the Nahualá patrol was able to apprehend several of the kidnappers: when the army came to take away two of the men, the local population said no, explaining, ‘We just want justice—we are doing exactly what Ríos Montt said to do’. When the army saw that they were not ‘controlling’ the militia, they ordered it disbanded. Again, the local patrollers refused. The army retreated, but returned several months later, imposing the official civil patrol under army vigilance and under the order to carrysticks and machetes. (Americas Watch 1986, 25)

The Guatemalan government was acutely aware of the threat that autonomous actions could pose to their long-term state-building project. Because rebels were active in the area, the state did not take immediate forceful action in this case to follow through with its demand, but it did impose containment and control mechanisms to keep the militia weak. Moreover, these state–militia interactions were characterized by back-and-forth pressures eventually terminating at an acceptable equilibrium given the conditions on the ground.

Though the number of patrollers outnumbered the number of soldiers in the official military by as many as 4 to 1, most sources estimate that no more than 10 percent had antiquated M-1 rifles or pistols, while the rest carried clubs or machetes (AW 1986). Official forces exerted significant contain and control measures over the militias that ultimately kept them operationally weak. In many cases, villages could only have one rifle and needed to be purchased from the army. Suspected subversive behavior, or failure to act according to the code of conduct, was frequently punished with beatings or kidnappings, and patrollers were regularly reminded that any attempt to defy the state would be interpreted as pro-insurgent activity (Bateson 2017).

In 1986, the government formally declared that participation in the PACs was no longer mandatory. Although some local groups demobilized at this time, many continued operating until the peace agreement in 1996. Among the rank and file, many civilian patrollers continued participating because they feared that the guerrillas would return and that the army would violently crack down on any accused subversives (Stoll 1993). At the national level, however, two major factors seemed to shape the relationship between the state and the militias: the severity of the rebel threat and the political reach of the state. By 1986, the rebellion was dwindling, and the military had developed an administrative presence in most aspects of the government and civil society (Kobrak 1999). The Guatemalan government understood its position relative to the rebels at this time, as evidenced by one military officer's comment during the 1991 ceasefire: “of course, [the military] will take away the weapon of patrol members who don't need them in the case of peace … At the moment that the aggression ceases, we'll need to enter into a process of neutralization of all the people” (quoted in Emling 1991). Clearly the state had no intention of allowing the militias to operate any longer than necessary.

As part of the peace accords in 1996, the PACs were effectively demobilized in only a few months. The efficiency of PAC demobilization was due to the fact that most rank-and-file patrollers were ready to return to daily life without war and because any patroller jefes that did not wish to relinquish their power had little means to resist. The institutional legacy of the civil patrols continues to exist in some rural communities where local interests coincide with state security needs (Bateson 2017), but the government's efforts to contain and control the autonomous capabilities of the militias allowed for the emergence of civil society that otherwise may not have existed (Fumerton and Remijnse 2004).

Janjaweed in Sudan

The origins of the civil wars in Sudan are complex, but the ethnic dimensions of the conflict did not emerge until the 1980s. To combat Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) insurgents in the 1980s, the Sudanese government stoked the economic rivalry between the largely nomadic, landless Arab tribes and the various ethnic groups represented by the rebels (Flint 2009). After a rebel attack on an Arab village in 1985, local villagers demanded protection. The Sudanese army, however, was relatively weak, overstretched, and had little administrative capacity to redeploy its official forces (Cockett 2010). Instead, the government decided to distribute “truckloads of … mostly AK-47s and G3 rifles” to Arab tribes “through native administrative structures and leaders” (Cockett 2010, 86). Owing to the weakness of the Sudanese state, the ethnic hatreds it fueled, and the material rewards for participation, the murahileen proliferated quickly before being reorganized under the Janjaweed umbrella by President Omar al-Bashir (Cockett 2010).

Ethnic tensions continued rising in Darfur throughout the 1990s amid an ongoing conflict with multiple rebel groups. By 2002, rebel forces had ramped up attacks against government targets in the region. Khartoum again wanted to mobilize and arm more militia forces, but some local Arab tribes as well as members of the military elite initially resisted Janjaweed expansion. Some in the military underestimated the severity of the rebel threat and thought that militias would not be needed to defeat the insurgency (Flint 2009). Most concerns about bolstering the Janjaweed were put aside in 2003 when the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and Sudan Liberation Army (SLA)—together comprising tens of thousands of highly motivated and well-armed rebel soldiers—jointly assaulted a Sudanese air force base. This event shocked Khartoum and signaled the true severity of the rebel threat. The government responded by establishing bases for militia training, providing salaries to militiamen that even exceeded those paid to the official army, and distributing heavy weaponry to the Janjaweed (HRW 2005). The result was a jointly orchestrated genocidal campaign against Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa villages in Darfur and elsewhere.

Despite overt joint operations between the military and Janjaweed, Bashir denied any linkage with these militias for over a decade. This informal relationship, however, was not an indication that the militias were unnecessary from the government's perspective. Instead, Khartoum increasingly found itself catering to the whims of militia leaders and co-opting them with financial resources and increased access to arms. In 2005, for instance, a few militia commanders expressed an interest in ending the conflict in Darfur. Khartoum responded by sending 2 million USD to the militia headquarters and the commanders quickly resumed the war effort (Cockett 2010). Again, militia leaders recognized the bargaining leverage they had over the state at this point, but the state was able to temporarily co-opt the groups and retain their partnership using alternative means.

While the insurgents in Darfur weakened over the next couple of years, militia leaders were profiting from loot and extortion and expanding their political influence in the region (Flint and de Waal 2005). Continued war now grew to be optimal for many militia factions. In 2005, the government and SLA began peace negotiations in Abuja, Nigeria. Representatives from the Arab militias were not allowed to participate (Flint 2009). The Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) was signed on May 5, 2006, with no guarantees related to pastoralist Arabs other than a promise to disarm and demobilize the Janjaweed. The Sudanese regime failed in this effort, in large part because of its own weak political reach. Unafraid of government suppression after Khartoum's feeble attempts to rein them in, many Janjaweed militias revolted by signing independent agreements with the rebels and attacking government forces (Flint 2009; Cockett 2010). One prominent defection was that of Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagolo's militia in 2007, whose betrayal and theft of military equipment stunned Khartoum. Despite his frequent threats and occasional attacks on government posts over the next year, the government was eventually able to buy his loyalty in 2008 with promises of military integration and financial benefits (Flint 2009). Still, the DPA quickly fell apart because of the actions of uncontained militia groups.

In 2013, the Janjaweed was reorganized into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), an official paramilitary arm of the Sudanese Intelligence Bureau led by Hemeti. After leading two more scorched-earth counterinsurgency campaigns in Darfur, “the RSF became al-Bashir's “praetorian guard,” tasked with protecting the president from any coup attempt by the army” (Al Jazeera 2019). In December 2018, mass protests against al-Bashir's rule broke out in Khartoum, and in April 2019, military officers deposed the president and established the, Transitional Military Council. As of this writing, Hemeti is the deputy head of the council and considered by many the most powerful man in the country (Al Jazeera 2019).

Case Discussion

The patterns of militia containment across these two cases were largely consistent with my hypotheses. After the militias were formed, the extent of political administrative reach and the severity of the rebel threat were the primary motivating factors influencing each state’s militia containment strategy. In Guatemala, the rebels were relatively weak, and the state's political reach was moderate and grew slowly in the early 1980s. Although patrollers had slightly greater autonomous capabilities in areas where insurgent activity was more severe, across both time and space, “the one constant in the behaviour of the military has always been an active attempt to subordinate and control them” (Fumerton and Remijnse 2004, 61). Moreover, as the threat posed by the rebellion subsided, the role of the PACs marginally changed, and the government began laying the social and institutional groundwork for demobilization (Stoll 1993; Schirmer 1998). The government took systematic steps to ensure that they never developed autonomous capabilities that would ultimately threaten its long-term state-building project. In Sudan, on the other hand, the regime depended on the militias to survive. According to a senior UN analyst, the “lack of long-term planning kills the government … it is trying to control the Janjaweed and build an officer corps, but its own weakness, and its system of bribery, with money and weapons, undermines its command and control” (quoted in Flint 2009, 47). This led to a vicious cycle in which the Janjaweed was granted significant autonomous bargaining power and the regime eventually collapsed. More generally, in both cases, militia containment levels were relatively stable in the aggregate, with marginal shifts corresponding to changes in the tides of war. However, the Guatemalan government was able to much more easily guide and control any minor changes in the militias due to higher levels of containment from the outset, whereas Sudan's lack of militia containment eschewed all hopes that the state could ever contain, control, or disarm the Janjaweed.

These cases also support the validity of the bargaining framework I propose. In both Guatemala and Sudan, the relationship between the state and militias was one of frequent interactions that were at times contentious. This illustrates that the political interests of local communities and militias did not perfectly align with those of the government, and militias have agency to attempt to pursue these interests. Dissident actions undertaken by militias often took the form of demands for greater independence from the government's state-building projects or more material resources that could eventually translate into increased future bargaining power vis-à-vis the state. Bargaining itself manifested through explicit actions by both sides to push the other to the limit when conflict dynamics on the ground significantly changed, and subsequently the implicitly “agreed-upon” containment equilibrium would remain relatively stable due to expectations about the other actor's preferences, capabilities, and constraints. Overt acts of resistance in Guatemala were relatively few, subtle, and localized, but when they did occur, the military responded with enhanced control mechanisms or brutal acts of repressive violence. Conversely, in Sudan, efforts to impose control over its militias were sporadic and feeble. Given the severity of the rebel threat in the short term and the state's consistently weak political reach, Khartoum had to prioritize short-term survival at the expense of future bargaining leverage.

Finally, in both examples, credible commitment problems played an important role in the interactions between the states and the militias. Khartoum could never credibly commit to suppressing its Arab militias and was punished by them when the government failed to provide the militias with sufficient post-war power and resources. Despite a close ethnic affiliation with the political elites in Khartoum, the Janjaweed then derailed the DPA, temporarily aligned with rebels, attacked government targets, demanded more resources, and ultimately seized power in Khartoum because the militias knew they could. The Sudanese government was forced to give away its bargaining leverage over the course of the war and then suffered the consequences. The PACs in Guatemala, however, were fully aware of the consequences of contradicting state interests because the environmental features of the war allowed the government to violently suppress militias or their members if they failed to acquiesce to state interests. The result was an acceptance among most militia members that it was in their best interest to participate in the war effort, fend off guerrillas, and, most importantly, avoid repression by the state.

Conclusion

In medieval Europe, “Cities commonly organized citizen militias which guarded walls, patrolled streets … and now and then fought battles against enemies of … the kingdom” (Tilly 1990, 55). Yet, even in an era wrought with war, “kings generally sought to limit the independent armed force at the disposition of townsmen, for the very good reason that townsmen were quite likely to use force in their own interest, including resistance to royal demands” (Tilly 1990, 55). These patterns of containment are prevalent in contemporary civil wars as well. In this article, I have argued that the level of militia containment during a civil war is a function of the severity of the rebel threat and the authoritative capacity of the state. These factors shape the bargaining process over future bargaining power between a state and its militia agents by altering whether the state can credibly commit to not eliminating the militia when it outlives its usefulness.