Modern medicine works indisputable wonders when it’s delivered carefully and appropriately. But it’s easy to forget how much harm it can cause when something goes awry. Medical errors kill an estimated 440,000 U.S. patients every year—well over 1,000 every day—and harm many times that number. The toll puts medicine itself in the same league as cancer and heart disease as a leading cause of death. Yet until recently, no one was even measuring the devastation, let alone working to reduce it.

That’s now changing fast, thanks in part to the nonprofit Leapfrog Group. Leapfrog’s Hospital Safety Score—a user-friendly report card launched last year and updated every six months—enables anyone to inspect the safety records of 2,523 acute-care hospitals at a glance.

“Medical errors kill a population the size of Miami every year,” says Leah Binder, Leapfrog’s president and CEO. “By showing the public how hospitals are safeguarding their patients—or aren’t—we give the whole industry an incentive to do better.”

Hospitals already report many safety-related practices and outcomes to Medicare officials and the American Hospital Association. But neither the government nor the industry group converts those data into rankings that a layperson can grasp.

Leapfrog uses the existing public data, along with its own voluntary survey, to track each hospital’s performance on 28 safety measures. After plotting all the scores on a bell curve, the group’s analysts give each hospital a letter grade that reflects its standing in relation to all the others.

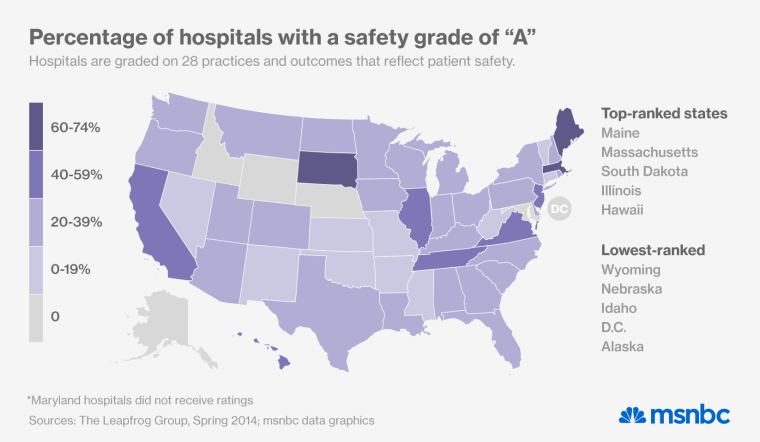

The latest grades, released Thursday, reveal some encouraging trends. Except for Wyoming and Washington, D.C., every state in the country has seen a slight increase in its hospitals’ safety scores. Nationally, the average score has jumped by 6% since 2012, and a third of all hospitals have raised their standing by at least 10%. Many have improved staffing and training, while adopting proven strategies to prevent infections, injuries and medication errors.

“More hospitals are working harder to create a safe environment,” says Binder, “and that’s good news for patients.”

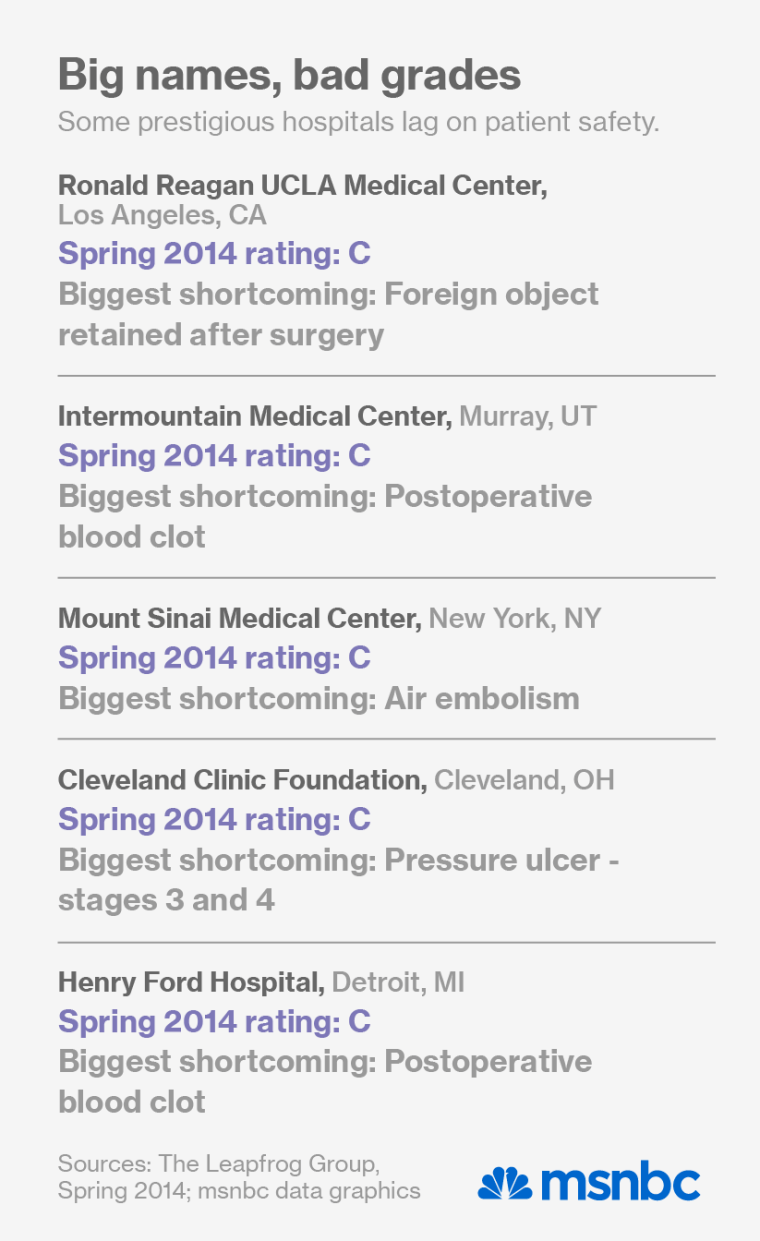

But the gains look awfully modest when you consider the remaining challenges. Nationally, 173 hospitals got grades of D or F, meaning they were 1.5 to 2.7 times more dangerous than those with A's and B's. In four states (Alaska, Idaho, Nebraska and Wyoming) and the District of Columbia, not a single hospital earned an A grade. And some of the country’s biggest-name institutions—from the Cleveland Clinic to UCLA’s Ronald Reagan Medical Center—received C's for patient safety. Some of them scored respectably on most measures but failed spectacularly to address preventable hazards such as falls, trauma and postoperative blood clots.

How do such mundane problems persist in such high-tech environments? Writing in the Journal of Patient Safety last fall, toxicologist John T. James offers a sobering list of contributors. “Our country is distinguished for its patchwork of medical care subsystems that can require patients to bounce around in a complex maze of providers as they seek effective and affordable care,” he writes. "Because of increased production demands, providers may be expected to give care in suboptimal working conditions, with decreased staff, and a shortage of physicians, which leads to fatigue and burnout. ... The picture is further complicated by a lack of transparency and limited accountability for errors that harm patients.”

The Leapfrog listings are a bold move toward transparency, and experience suggests that alone can shame business interests into better behavior. Food poisoning fell sharply in Los Angeles during the late 1990s, after sanitary inspectors started posting letter grades in restaurant windows. New York City saw a similar decline after it adopted the practice in 2010. “Restaurant letter grades were our inspiration,” says Binder. “I wish hospitals had to paste safety grades in their windows.”

Since they don’t, the Leapfrog group has developed iPhone and Android apps that anyone can use to check hospital safety grades by name or location. “This spring we saw eight million people sign up for health insurance via the Affordable Care Act,” Binder says. “As they launch a search for health care providers, we’re urging them to put safety first and look for an ‘A’ hospital in their area.”

If that happens, hospitals may yet achieve the kind of progress that restaurants have made in New York and Los Angeles. But no one expects transparency alone to stop the epidemic of hospital hazards. Under The Affordable Care Act’s Value-Based Purchasing provisions, Medicare now rewards hospitals for meeting various quality measures, and penalizes those that fall short. The incentives have changed only modestly so far, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will expand them in coming years to address more safety issues. As a Georgia hospital executive told Kaiser Health News last fall, “The thing about the government, if they start paying attention to it, we have to scramble around to pay attention to it. It gets us moving.”

American medicine is changing, but it can still be hazardous to your health. So don’t take those gauzy, feel-good hospital ads too seriously. As Binder wrote in Forbes on Tuesday, “transparency is not public relations, but cold, hard data supplied through reliable sources, scrubbed, vetted, and checked for validity.” That’s why the new Leapfrog grades are so valuable.